Want a crash course in states’ rights? Look at how they handle their liquor. Since Prohibition, each state has been given broad latitude to regulate the hard stuff as they see fit. Mississippi, for instance, was dry through 1966. Kansans didn’t order their first drink at a bar until 1987. And South Dakota, infamously, kept its drinking age lower than everyone else, until it was baited by the promise of federal highway funds.

And part of states’ rights includes the way they handle interstate commerce. Generally speaking, the Commerce Clause of the Constitution allows for most foods to cross state lines. That’s not the case with liquor, though. Most states require salesmen to be true residents, having lived within their boundaries for a given number of years.

But that’s about to change. Yesterday, the Supreme Court decided that those residency provisions are unconstitutional, ruling against a Tennessee trade association by a 7-2 vote. As a result, it’s likely that more retailers will start selling their wine across state lines—a victory for drinkers seeking cheap prices, and perhaps, for companies hoping to ship their wares more widely.

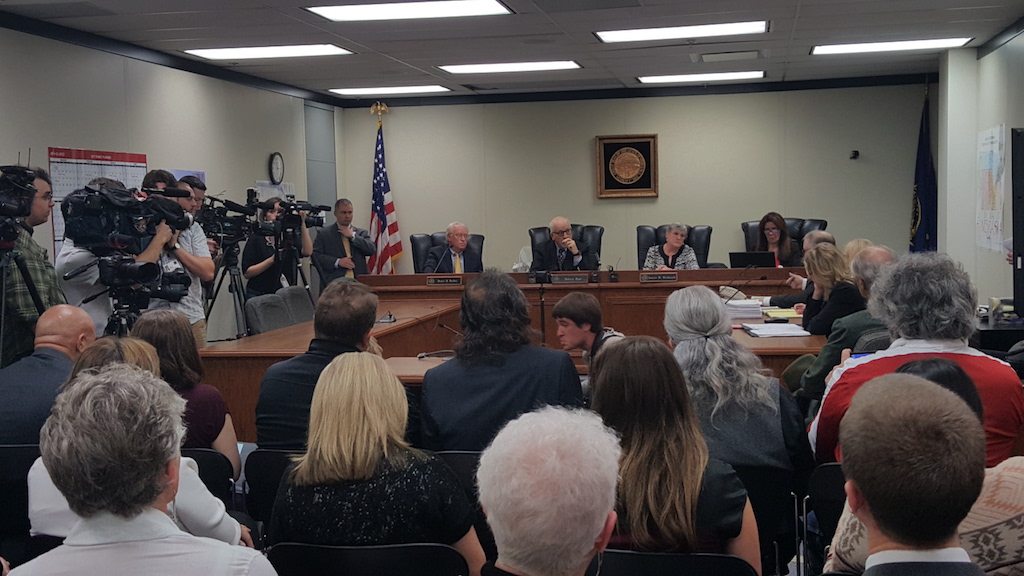

After the Tennessee Alcoholic Beverage Commission (TABC) approved their petitions, the Tennessee Wine and Spirits Retailers Association (TWSRA) appealed, saying that neither applicant was legally allowed to have a license. Tennessee is one of 35 states with a residency requirement for selling liquor. In this case, the trade association pointed out, neither applicant had been living in the state for two years. Additionally, the law requires 10 years of residency to renew the license, and for all company stakeholders to be residents, too.

Lower courts found that Tennessee’s law was unconstitutional, but TWSRA took their suit against Russell F. Thomas, the commission’s executive director, all the way to the Supreme Court. The association said their law is protected by the second section of the 21st Amendment, which overturned prohibition. That particular section gives states the options to stop the import of liquor across their borders.

And again, it’s failed to persuade the court. Justice Samuel Alito, writing for the majority of the court, said the state’s two-year residency requirement, which doesn’t have an effect on public health or safety, is unconstitutional, and a violation of interstate commerce laws. Theoretically, that 86-year-old clause could be enforceable. But more recent precedents, including a 2005 court decision that gave out-of-state wineries greater latitude to ship to customers in New York and Michigan, have “rejected that view,” Alito wrote. The clause “is not a license to impose all manner of protectionist restrictions on commerce in alcoholic beverages.”

Tom Wark, executive director of the National Association of Wine Retailers, a trade association that had submitted an amicus brief, cheered the decision.

“State alcohol laws that discriminate against out-of-state retailers for the purposes of protecting in-state interests are unconstitutional and not protected by the Twenty-First Amendment. The decision is a historic win for both free trade and wine consumers across the country,” he said in a press statement.

“With this decision, the effort to modernize and bring fairness to the distribution and wine shipping laws of the states begins in earnest. While we expect the opponents of free trade and supporters of protectionism to fight this evolution in the American marketplace, we are equally confident that this Supreme Court decision will lead to greater access to the hundreds of thousands of wines many consumers do not currently have access to due to protectionist wine shipping laws.”

In other words? Get ready to start seeing more liquor waiting for you at the doorstep.