USDA / Preston Keres

With a little hot glue and a lot of patience, researchers are turning chicken movements into raw data—and using that information to detect health problems.

Birds love backpacks. Or rather, scientists love birds with backpacks, because microcomputers hitching rides on the Two-Wing Express can tell us all sorts of things about the world, like where golden-cheeked warblers spend their winters, what’s going on with the climate, and how sparrows teach songs to one another. (Backpacked birds also hold appeal for creative drug smugglers, ice sculpture event promoters, and The Counter’s Covid-fatigued newsroom, but that’s neither here nor there.)

Amy Murillo

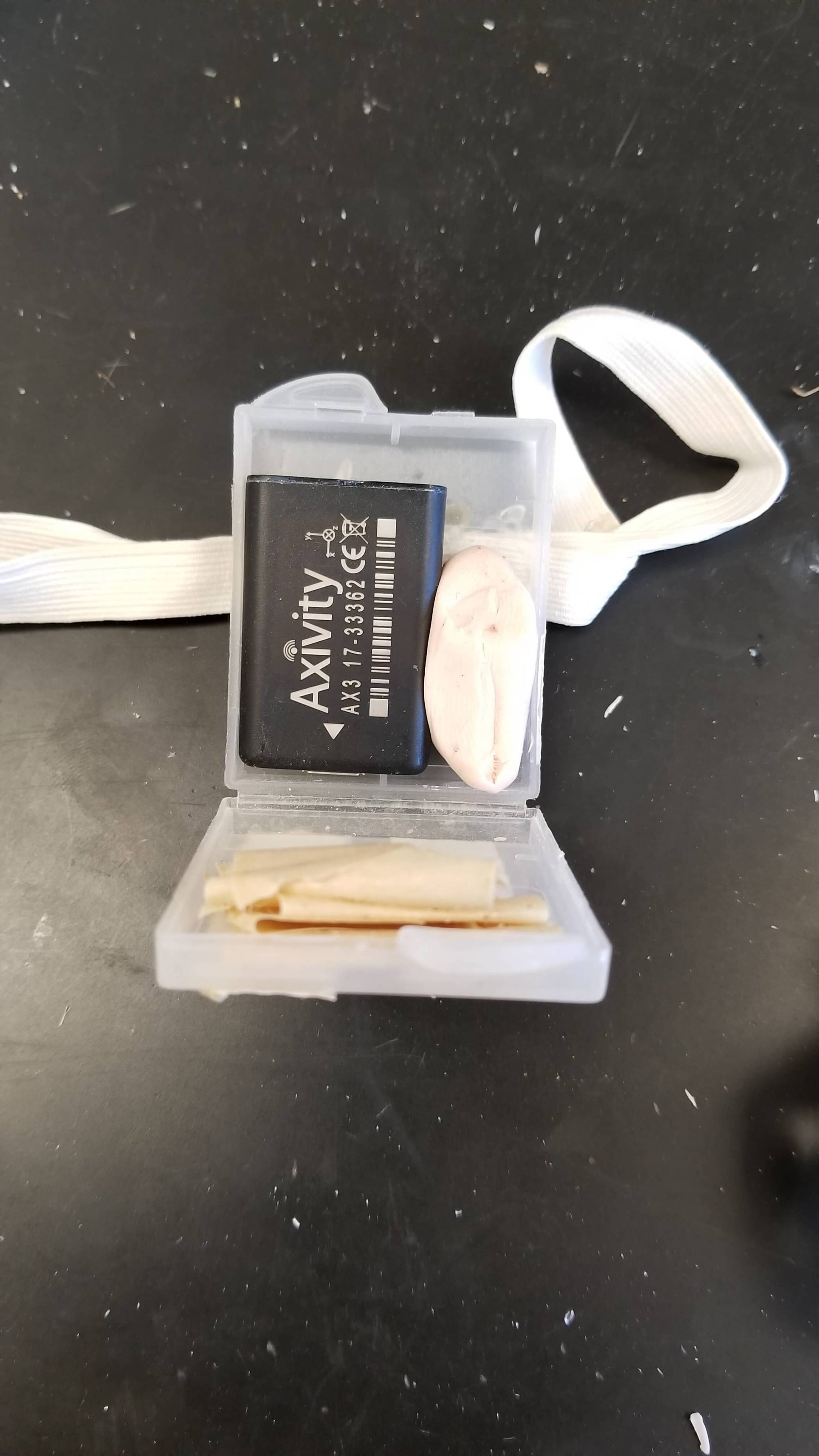

Murillo hand-built the sensor backpacks with plastic GoPro battery cases and hot glue.

Still, birds don’t really dislike backpacks, according to University of California-Riverside entomologist Amy Murillo, who had the distinct pleasure of outfitting about 50 chickens with motion-sensing wearables as part of her research on a particular species of mite she compares to “living vampires,” which latch on to chickens’ rear ends and suck their blood. “Pretty much within about two minutes of putting the backpacks on, they were back to doing their thing,” Murillo said of the birds in their back-to-school finery.

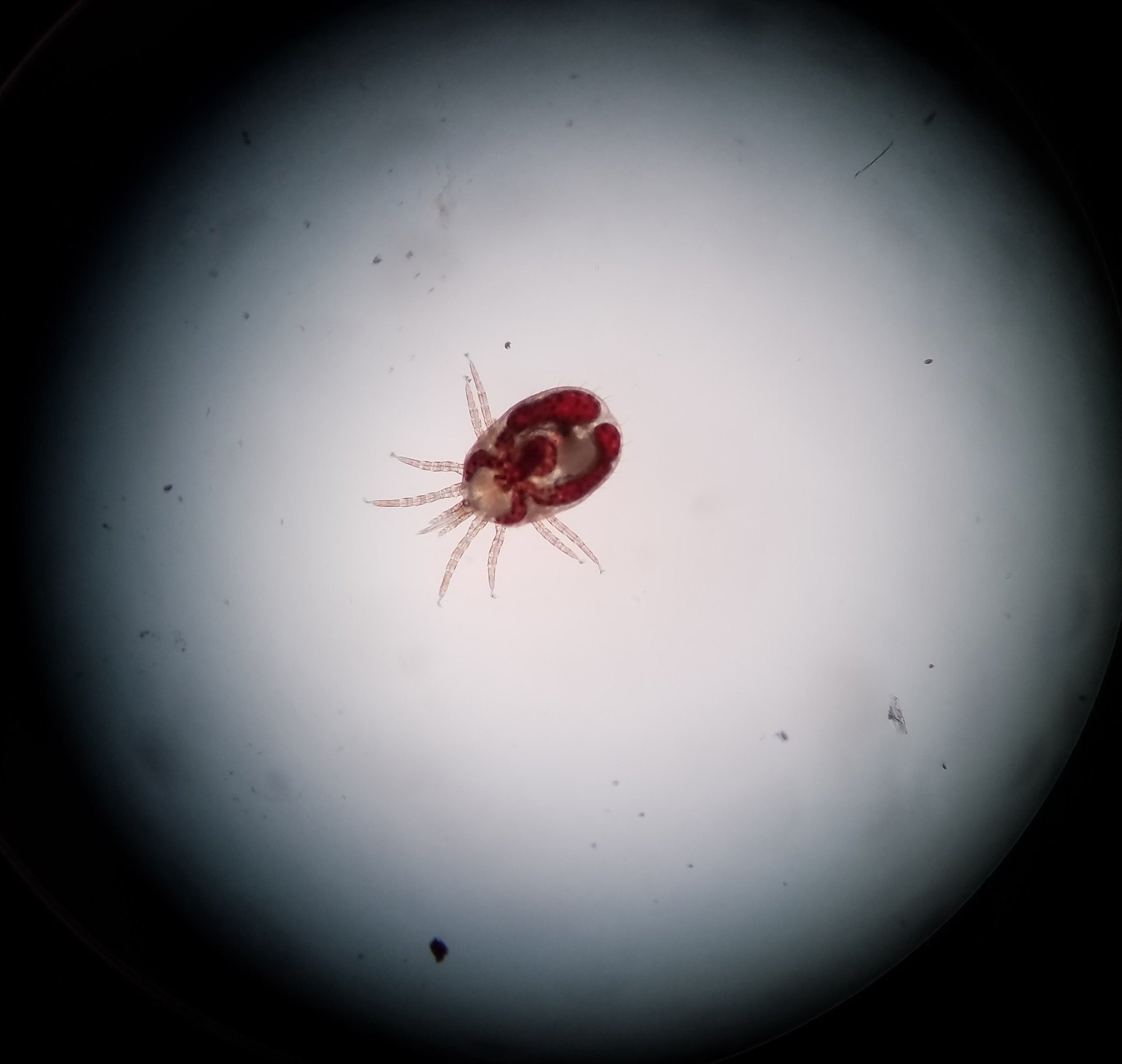

The northern fowl mite is a common parasite, particularly in flocks of laying hens. But little research has been devoted to its impact on its host’s quality of life. “Animal welfare has been an increasing topic of study, and it’s increasingly important. But what I’ve found is that it completely ignores other metrics that are being used—it completely ignores the active parasites that could be present in chickens,” Murillo said. She wanted to learn more about the potential negative impacts of mite infestations on laying hens, and quantify those impacts.

Chickens normally spend their days pecking, preening, and dust-bathing. When they’re feeling good, most of their time is spent pecking—foraging for insects, exploring their surroundings, eating clover. But their behavior changes when northern fowl mites start to sink their teeth in: They preen more often and take dust baths, potentially signaling discomfort.

To track the birds’ behaviors in real time, Murillo hand-built the backpacks with plastic GoPro battery cases and hot glue. “Entomology is the science of studying insects—we are used to having to build things ourselves because people don’t make things to study insects. So it’s very much an arts-and-crafts science sometimes,” she said.

“Pretty much within about two minutes of putting the backpacks on, they were back to doing their thing.”

Once the chickens were equipped with backpacks, the sensors sent a live stream of data showing the birds’ activity in wave patterns. Computer scientists were then able to match each wave shape to its corresponding activity. From there, they could chart changes in the animals’ behavior over time.

The data showed a strong relationship between preening behaviors and mite levels. The chickens tolerated low numbers of mites without much behavioral change, but once the parasites were well-established, they began preening more. This suggests that motion-sensing technology might be useful in tracking mite levels across large flocks by strapping backpacks to a few sentinel birds and monitoring their behaviors, ultimately making sure egg production and flock well-being aren’t compromised.

The backpacks might also be useful for tracking other health metrics, Murillo said. Low activity levels might suggest the presence of diseases like avian bird flu or virulent Newcastle disease. Other pathologies, like lameness, could signal infections or other issues.

Amy Murillo

The northern fowl mite, a common parasite affecting flocks of laying hens.

If backpack-style Fitbits for flocks take hold among egg farmers, they won’t be the first to appropriate tracking technology in the name of chicken monitoring. In China, the insurance-tech firm ZhongAn is already using GPS devices to market so-called “gogochickens”: birds that are fitted with ankle bracelets as chicks, and send data throughout their lives. Customers buy individual chickens and track their progress as they grow, monitoring their exercise, food consumption, and location through a smartphone app. The company is even contemplating facial recognition technology to snap shots of the birds as they scratch and peck.

Poultry privacy concerns aside, wearable tech may mean a leap forward for general chicken contentment. On the other hand, northern fowl mites might have to wait awhile for backpacks of their own.