iStock / kcline

Researchers have found great preservation results, simply by coating strawberries and avocados in a thin layer of “egg wash.”

This past weekend, foodie Internet was set ablaze over rumors that the popular L.A. restaurant Sqirl had served moldy jam. Consequently, the mold explainers rolled, outlining what exactly mold is, whether or not to put it in your mouth, and how to deal with food that’s gone bad. But how can we extend the shelf life of our favorite foods and keep them from going bad in the first place? According to food technology researchers, coating them with a thin coating of egg—yes, egg—might be one way to do it.

In a novel experiment, scientists dipped strawberries, avocados, bananas, and papayas into a mixture of egg white and egg yolk and monitored changes in shelf life over time. What they found was yet another use for a food that is already remarkably versatile: Compared to unadulterated produce, the egg coating kept produce fresher for a longer period, not only in appearance, but also in water retention and firmness. In some cases, egg coatings appeared to perform even better than carnauba wax, the popular ingredient that keeps apples and oranges as intensely shiny as they are at the grocery store.

These findings were documented in a recent article published in peer-reviewed journal Advanced Materials. The study’s authors were aiming to find a protein-based alternative to wax coatings that could keep produce just as fresh.

“What we found is that when you coat fruit with this coating method…it improves shelf life significantly.”

“Egg is a good source of protein, [so] that’s where we started,” says Maksud Rahman, a research scientist at Rice University and one of the study’s authors. Rahman’s team sought to “see how this egg protein can behave and [whether it] can act as a shelf-life extender.”

Researchers created their coating by egg white powder—which is shelf stable—with water, then adding in trace amounts of egg yolk powder, glycerol for flexibility, cellulose from wood pulp crystals for durability, and a turmeric extract called curcumin for antibacterial purposes. Then they dipped four test fruits—strawberries, bananas, papayas, and avocados—fully into the mixture by their stems to coat them, Snow White-style, twice.

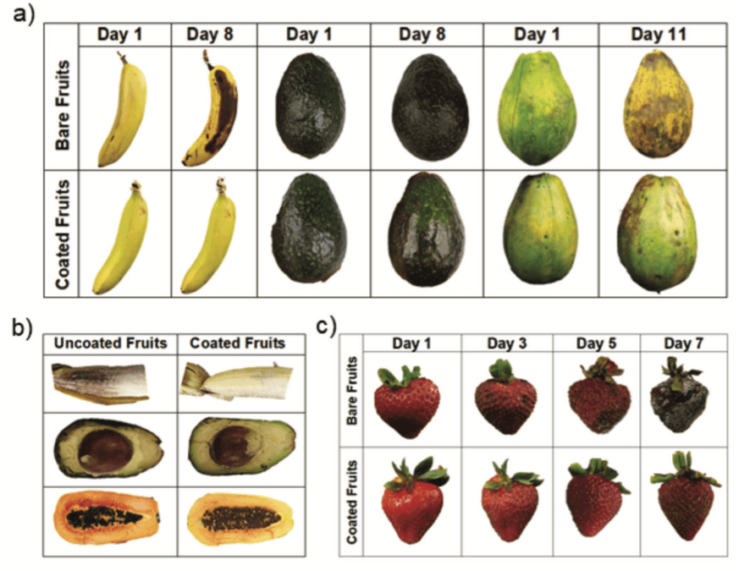

Over the next two weeks, the study’s authors monitored both the coated fruit and an uncoated control, comparing them visually, and checking for stiffness and weight over time. Uncoated produce ripened, and in some cases rotted to a point of being inedible, within a week. Coated fruit, on the other hand, faced minimal degradation, retained most of its water weight, and generally held up better.

Copyright Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA. Reproduced with permission.

A side-by-side comparison on bananas, avocados, papayas, and strawberries that were coated with an egg wash, compared with ones that were not.

“What we found is that when you coat [fruit] with this coating method…it improves shelf life significantly,” Rahman says.

To figure out why, the study’s authors looked into how exactly the coating reduces oxygen exposure and water loss—two conditions that contribute to ripening. Generally speaking, the study notes, minimizing oxygen around fruit can slow down its ripening process. Water retention, on the other hand, prevents produce from wilting, which is inevitable after it’s harvested—but it can be delayed, the Food and Agriculture Organization explains. Peels and skins and rinds can slow down the speed at which water leaves fruits and vegetables, while coatings—like wax or egg washes—can serve as additional reinforcement, keeping fruit fresh and juicy longer. The egg-based coating, as it turns out, did both: It limited each fruit’s oxygen exposure and prevented water from evaporating.

(While the egg coating is obviously not vegan, for those of you concerned about an egg-y taste on your produce, the study’s authors also found that the coating easily and completely dissolves upon washing for two minutes.)

It’s tempting to read this development as a preventive against food waste, an issue that has been framed as urgent, pervasive, yet solvable. The Department of Agriculture’s (USDA) Economic Research Service estimates that almost one-third of the foods that reach store shelves or eaters’ homes don’t actually end up in our stomachs.

The team is looking into testing alternatives created with soy and corn protein, both of which sidestep the common issue of egg allergies and can also increase the value of two major U.S. commodities.

“World hunger is a rising issue,” the study’s authors write. “This is largely due to perishable foods expiring during or shortly after the time it takes to distribute foods from farms to retail stores.”

However, as the Covid-19 pandemic has laid bare, produce largely gets wasted not because it goes bad too quickly—but because our food distribution systems are inflexible, heavily consolidated, and maintained by workers who don’t have adequate social and health protections. And food insecurity—which has risen rapidly during the public health emergency‚ has less to do with how quickly cantaloupes ripen, and more to do with the fact that households literally don’t have grocery money.

The real potential of the study’s success with egg wash coating doesn’t even involve eggs, Rahman tells me. Rather, he sees this experiment as a jumping off point for other protein-based produce coatings. Next up, the team is looking into testing alternatives created with soy and corn protein, both of which sidestep the common issue of egg allergies and can also increase the value of two major U.S. commodities.

For eaters, the question of whether your apples are coated with wax or protein is probably much less urgent. It’ll all come out in the wash.