The Small Business Administration’s (SBA) Office of the Inspector General (OIG) on Tuesday announced in a new report that most chicken growers may no longer qualify as independent, small businesses. And that means they won’t qualify for small business loans.

It’s a finding that could signal a significant loss in support: Between 2012 and 2016, SBA loaned about $1.8 billion to poultry growers. In 2016, poultry companies received more than three-quarters of all the SBA loans that went to agricultural businesses.

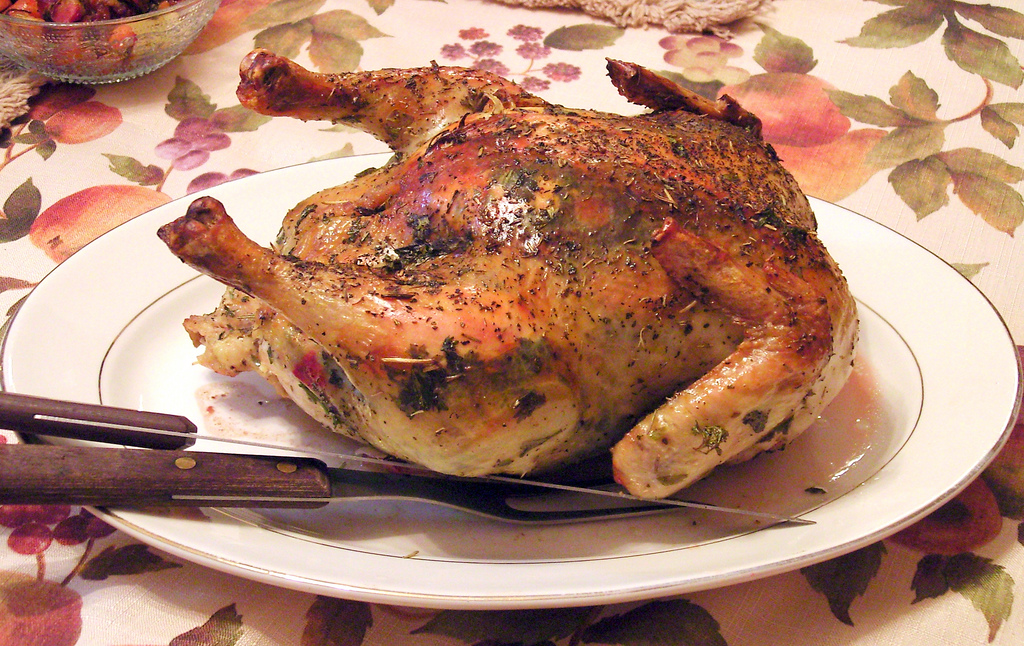

In case you don’t live as deeply down in the weeds as we do, here’s how the vast majority of chickens in the United States are grown: They’re hatched at a facility owned by a meat processor—also known as an “integrator” (that’s Tyson, Perdue, Sanderson Farms, and Pilgrim’s Pride). Those chicks are then delivered, along with feed and antibiotics, to a number of different farmers. The farmers care for them for a few weeks while they grow up, then take them back to the processor, where they’re sold in a competitive auction system that effectively pits farmers against one another. We’ve reported extensively on this system—first, in Joe Fassler’s account of a bankrupt contract grower, and later, when the Trump administration backtracked on Obama-era rules that would’ve tipped the scales ever so slightly back in favor of the small farmer.

Back to SBA’s findings. Contract growers might need loans for a variety of reasons—to get their farms up and running, for instance, or to make expensive, integrator-mandated enhancements and updates to their facilities, which can cost anywhere from $10,000 to as much as $350,000 or more. The average loan to poultry growers in 2016 was a little over $1.25 million.

The SBA has a technical term for being so closely linked to a giant corporation that you’re effectively not an independent business. It’s “affiliative.” And that’s important because if contract growers are considered affiliates of the large processors they work with, they can’t technically be considered independent and qualify for small business loans.

Congressional staffers brought that concern to the attention of SBA, and it launched an independent audit on poultry industry loans. Tuesday’s report shows that the administration essentially agrees with those staffers, saying, in effect, that chicken growers don’t meet the requirements to be considered small businesses because every aspect of their operation is controlled by a corporate … sorry … overlord.

“This control overcame practically all of a grower’s ability to operate their business independent of integrator mandates,” SBA wrote in its report. And its conclusion was backed up by an analysis of defaulted loans: A farm worth nearly $2 million when it had an integrator contract fell to just $135,000 in value in its final liquidation.

“When SBA loans go to firms that aren’t supposed to receive them, it means there are fewer resources available for deserving, small businesses who struggle to secure capital,” Representative Nydia M. Velázquez (D-NY), the top Democrat on the House Small Business Committee, said Wednesday in a press release. “The findings in the OIG report are profoundly troubling and I look forward to working with Chairman Chabot to exercise vigorous oversight, including potentially holding hearings in the future.”

Capital is tough to come by for any enterprise. And most of us would probably say we want small business loans to go to small businesses. But there’s an important nuance worth pointing out when it comes to contract farmers. Grower advocates argue that the contract poultry farming system is controlled so completely by large meat processors that a loan from SBA effectively subsidizes the Tysons and the Perdues of the world. They say the system has been rigged from day one in an elegant equation that creates reliable profit margins for the processors while outsourcing all the real uncertainty and risk (weather, disease, mortality) to the farmer.

By pitting farmers against one another in the industry’s notorious “tournament system,” the processor ensures it’ll always pay rock-bottom prices for the grown birds. Only the luckiest farmer wins, while Tyson, for instance, reaps the rewards. And when the relationship doesn’t work out, processors can emerge unscathed while the farmer is left vulnerable, with a load of debt and a couple of chicken houses that can’t really be used for anything else.

So, what would happen to chicken growers if they were to actually lose out on SBA loans? For starters, it would be a heck of a lot harder for them to finance the big improvements their processors require.

But SBA’s findings have bigger implications than that. If poultry growers can’t really qualify as independent, small business people, shouldn’t it fall on the big processors to finance the expensive equipment and upgrades they requires from their farmers? Processors make the bulk of the profit, so it follows that they would be responsible for keeping the lights on in their own chicken houses.

Let’s look at it this way: What if SBA decides Uber drivers aren’t independent contractors? Uber certainly controls the bulk of that equation: the price of the ride, the quality of the app, the route, and the number of passengers at any given time. But at the same time, Uber’s not responsible for any of the risky stuff like vehicle maintenance, gas money, or car insurance. So while it gets to capture whatever profits the drivers make, it neatly side-steps any messy obligations that involve actual cars on actual roads carrying actual people.

Perhaps unfortunately for contract growers, SBA doesn’t actually have the power to change the way that businesses are structured or contracts are written. Its decision about whether or not an entity can be considered a “small business” is only as valuable as its particular loans. Still, the report represents a pretty existential shift in the way government entities have thought (or not thought) about how poultry integrators do business.

The strange thing about the parsing of small business status in SBA’s report, though, is that it ultimately punishes the grower for the lack of control she has over her own profession. You’re controlled by Tyson, SBA seems to say, so we might have to cut off access to these loans that help you meet Tyson’s demands. It may all be meant to staunch the flow of government money to Tyson’s coffers, but it may also make life harder for the smallest growers in the process.