So what the hell is soy leghemoglobin, and why is everybody so worked up about it?

I ask because of the outpouring of articles I’ve seen in the last week or so, including some that cast aspersions on the plant-based food startup Impossible Foods and the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), written in response to Stephanie Strom’s recent article in The New York Times. The piece described a set of documents, obtained by FOIA request, in which the company and the agency exchanged views about soy leghemoglobin, and whether it’s safe to eat.

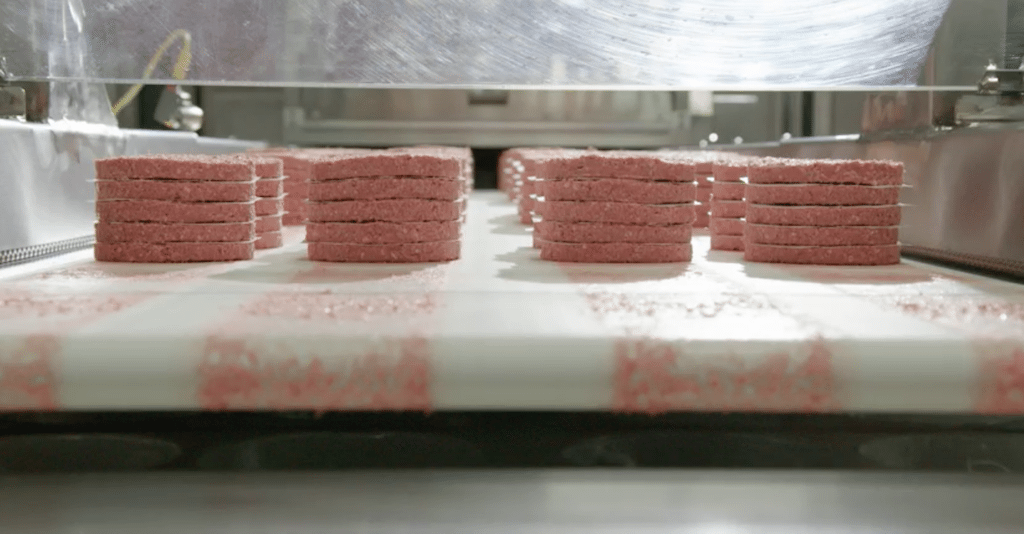

Make no mistake: This is a critical distinction for Impossible. The company’s futuristic vegan burger is designed to be meat-like enough to satisfy carnivores, down to the plant-based “blood” it oozes when cooked medium rare. (Our review is here.) That added touch, which Strom called Impossible’s “special sauce,” is made from the stuff the company discussed with FDA, and took years and many millions to develop.

Though the original story, apparently inspired mostly by dedicated anti-GMO activists, left a lot to be desired—as you can read in Nathanael Johnson’s level-headed critique for Grist—the best part of the story seems to have been swallowed in the subsequent debate. The real point here is not the controversy. It’s what the back-and-forth reveals about how cutting-edge plant-based technology works, and how scientists, for better or worse, make their determinations about what’s safe or not. This stuff is only going to matter more down the line, as food technology continues to evolve. It pays to get it right.

First off, what is soy leghemoglobin, and why is it in the Impossible Burger in the first place?

Leghemoglobin is a globin—one of a group of globe-shaped proteins found in animals and plants. The globin you are probably most familiar with is hemoglobin, which transports oxygen from your lungs to the rest of your body, and which gives blood its red color. Leghemoglobin is a plant globin, and soy leghemoglobin is the variant found on the root nodules of the soy plant. There, it cooperates with colonies of specialized bacteria to convert nitrogen into forms that the plant can use to nourish itself. Anything left over when the plant dies goes back into the soil, where other plants can use it. That’s why “nitrogen-fixing” plants like soy and alfalfa are built into crop rotation schemes: They increase the available nitrogen in the soil.

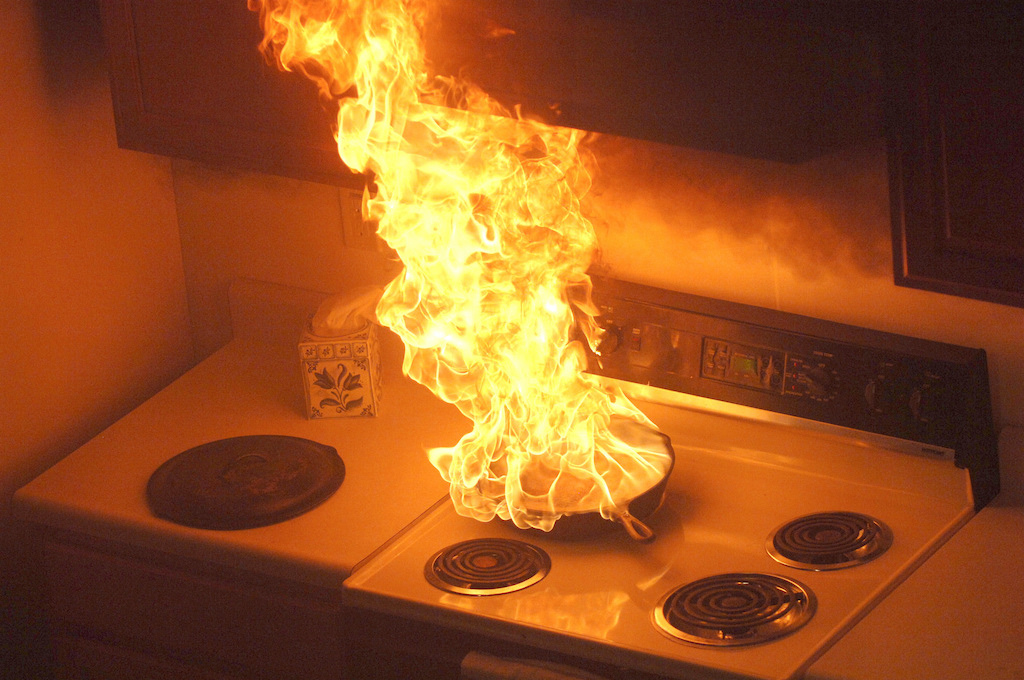

The active ingredient of globins, the thing that lets them work their magic with oxygen and nitrogen, is a molecule called heme, which sits wrapped up in the amino acid chain of the globin. When you heat up an Impossible Burger, the leghemoglobin releases its heme, just the same way myoglobin in beef would release its heme. Iron-rich heme is part of the characteristic flavor of meat—which is why Impossible wanted it in the first place.

If it’s just part of soy, what’s the problem? There are actually two problems. First, though humans consume all sorts of globins in all sorts of forms, it appears that they haven’t gotten around to eating soy leghemoglobin before. People eat soy beans, of course, and they also consume a variety of plant products that contain various sorts of leghemoglobin—think bean sprouts. Cows grazing on alfalfa sometimes consume root and all, taking in leghemoglobin with no apparent ill effects. But if people or livestock have been eating soy root nodules, they haven’t gone public with it.

The second problem: The soy leghemoglobin Impossible uses in its burgers doesn’t come directly from soy plants. Instead, Impossible has implanted the soy gene responsible for creating it in yeast cells—specifically Pichia pastoris, one of the workhorses of biotech. The manufacturers brew up the modified yeast, much the way you’d brew beer, but with the yeast releasing a globin instead of alcohol, and then they filter out the yeast and other byproducts until the leghemoglobin is about 80-percent pure.

So is Impossible’s leghemoglobin a GMO? Nope. It’s not an organism at all. It’s a protein produced by genetically modified yeast cells. That’s an important distinction under current law, though it doesn’t seem to matter much to the most ardent anti-GMO folks. For what it’s worth, let’s not forget that modified cells—yeast, E. coli, Chinese hamster ovary cells, and even human cancer cells—have been used for decades to produce dozens of drugs that couldn’t be manufactured any other way using current technology. Recombinant human insulin has largely replaced the earlier form that was extracted from pigs, and we’ve seen the arrival of a host of recombinant antibodies and other proteins to treat cancers, rheumatoid arthritis, and other diseases. Like any drugs, they have their dangers, and they’re expensive to develop and manufacture, but the overall safety of the approach seems beyond question at this point. Which doesn’t mean that anything you create through cell culture is automatically going to be safe.

So how do you tell whether it’s safe? The big concern with proteins is food allergies. All of the “big eight” allergens—eggs, milk, soy, fish, shellfish, wheat, peanuts, and tree nuts—contain protein in varying amounts, and most are high in protein. So Impossible hired an outside lab to analyze its leghemoglobin. The lab did a literature search and found that not only was leghemoglobin not associated with allergies, but the whole globin class was free from allergy reports, with the exception of a single report of a reaction to cow myoglobin.

Next it compared the structure of the protein to analogous hemoglobins, known to be safe (from a variety of plants and animals) and concluded that the soy leghemoglobin had no features—that is, external structures it could use to hook itself onto cells in the body of someone who had eaten an Impossible Burger) It compared the amino acid sequence of Impossible’s protein with known allergens, looking for shorter stretches that might be allergenic. They noted a stretch that bore a 35-percent resemblance to a minor allergen found in potatoes, but concluded it wasn’t a strong enough resemblance to cause problems.

Finally, they conducted a digestion test. Apparently foods that cause an allergic reaction tend to be not very digestible. If you find a protein that isn’t digested in a lab version of gastric juices in eight minutes or so, that’s a red flag. Impossible’s leghemoglobin was 90 percent digested in 30 seconds and completely gone in a minute.

(Here’s a point worth noting: A protein is a long chain of amino acids folded into a specific shape. It’s the shape that gives it its ability to get things done in the body. A protein can be “denatured”—unfolded and robbed of its bioactivity—by a number of factors including heat and acidity. The leghemoglobin in the Impossible Burger is supposed to denature during cooking: that’s the thing that releases the heme, and it’s the whole point of including the leghemoglobin in the first place. So most of the leghemoglobin is supposed to be biologically inactive by the time it hits the gut. It’s highly digestible, but it’s not really supposed to get the chance to be digested.)

Meanwhile, the yeast and the nutrients it feeds on are well known, widely used, and safe. The non-modified version of the yeast is a permissible part of chicken feed, and modified versions have been used in several FDA-approved drugs. The process of fermenting the yeast and the techniques used to separate out the protein from the soup are well known and understood. (In particular, in case you were wondering, the burger doesn’t contain any of the yeast or the DNA the yeast once contained, though it does contain small amounts of the proteins it naturally produces.)

And FDA said what? You have to understand two things: First, Impossible didn’t need FDA approval. Its leghemoglobin falls under the GRAS (generally recognized as safe) regulations. The company certifies the stuff as safe itself. It doesn’t have to consult FDA. It did, though, and that was a smart idea. On the one hand, it helps head off inevitable lawsuits. On the other, if Impossible wants to bring novel ingredients to market, it needs to be good at GRAS, and FDA is happy to help. Lots of companies seek FDA input on their GRAS filings.

Thing two: FDA is not known for saying, “Yup, this application is perfect.” It tends to want a bit more. That’s what it did this time, asking for more characterization of the yeast proteins and an animal trial and some other minor modifications to the documentation. By FDA standards, not a big deal at all, and very typical. The Impossible dream is still alive.

So what should we take away from all this? Honestly, not all that much. If you dive down into the documents, it really looks like a tale of conscientious professionals on both sides doing their job in a confusing new realm of activity, sometimes disagreeing, sometimes talking at cross-purposes, but doing what they’re supposed to. (Could there be hidden villainy here? Of course, but at least it’s not obvious. These days that should count for at least something.)

If you weren’t aware of how important molecular-level analyses have become to food safety, that’s something you want to know—though I suspect not everyone will regard it as an improvement. If you look at the GRAS process and are horrified at the idea of self-certification, you might want to write your congressman, though realistically there are much bigger fish to fry at FDA, and you might not want to distract those poor overworked people. I personally note that the Times let us down on this one. Their story kind of missed the boat.

One last little irony: In the end, what’s going to confirm the safety of recombinant soy leghemoglobin (or “modified soy protein,” as Impossible plans to call it) is a test where someone will feed vast quantities of the stuff to lab rats—animals suffering to prove the safety of a plant-based burger.

Picture a late-night meeting in the rat lab. A grizzled old vet harangues his fellow rodents: “Rats gotta suffer so cows can live,” he says. “Ain’t that always the way.”

Well, ain’t it?