In case you’ve missed it, the state of Maryland has been embroiled in a long-winded tug-of-war that has entangled conservationists, oyster harvesters, and lawmakers for months. In one corner, there’s the urgent push to restore depleted oyster populations. In the other, watermen who see conservation efforts as limitations on their cultural practice and economic lifeline.

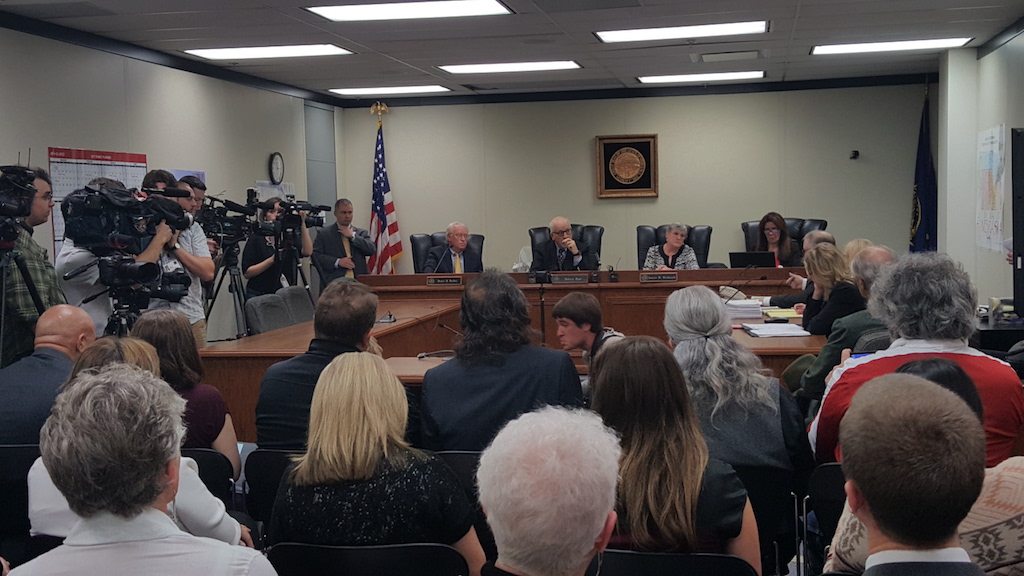

In the most recent salvo, the Maryland state senate just voted to override a contentious veto on a bipartisan bill to restore oyster populations. By doing so, it joins the state house in enshrining into state law the preservation of five large-scale oyster restoration projects in the Chesapeake Bay by permanently banning wild harvest of oysters within their boundaries.

It all began on January 28, 2019, when the late Democratic speaker of the state House Michael Busch introduced a proposal that would designate five tributaries in the Chesapeake Bay as key oyster sanctuaries and prohibit harvesting within these areas. The Chesapeake Bay is North America’s biggest estuary, and its many waterways sustain a wide range of ecosystems and economic activities.

However, pollution, disease, and overharvesting have severely depleted its formerly abundant supply of oysters. Oyster populations in the upper Chesapeake Bay, the area surrounded by the state of Maryland, had declined to 0.3 percent of early 19th century levels in 2011, according to a study from the University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science.

Busch’s bill focuses exclusively on oysters, establishing clear and detailed boundaries for five of the Bay’s most effective restoration areas, ban harvesting within their limits, and direct the state department of natural resources to pursue further restoration efforts with the aim of meeting the goals established in the 2014 agreement.

The proposal passed in the house with bipartisan support on March 26. Its corresponding bill in the Senate passed on April 2.

That’s when things started to get complicated. Though the bill had widespread support by conservation groups, it was seen as an anathema by oyster harvesters—yet another restriction that would jeopardize a crucial source of income.

“We’ve got to build this business back up,” says Robert T. Brown, president of the Maryland Waterman’s Association, a nonprofit that advocates for commercial fishers. “This is our way of life, our livelihood, and our heritage and we want to rebuild it.”

Instead, Brown suggested rotational harvesting—where tributaries alternate between restoration and harvesting—as a compromise that would allow both activities to coexist.

Chesapeake Bay Foundation

Chesapeake Bay Foundation The five oyster sanctuaries whose preservation will be codified in state law

However, Don Webster, an extension agent at the Maryland Sea Grant for the past 44 years, doesn’t see this as an acceptable middle ground. Webster points out that Busch’s bill protects just five of 60 oyster sanctuaries in Maryland. If oyster levels in the Chesapeake Bay are ever to be restored to historic levels, it’s necessary to have dedicated areas for conservation.

“If the watermen want to come up with a rotational harvest plan for [other sanctuaries], I think they should certainly be able to.”

The harvesters’ concerns did capture the attention of Republican Maryland Governor Larry Hogan, who vetoed the bill on Thursday of last week—an unexpected move given that it had passed by veto-proof margins in both chambers of the legislature. The next day, the House voted to override Hogan’s veto.

Then, in a tragic turn of events, Busch died on Sunday afternoon at 72. He was the longest-serving speaker of the House.

On Monday, the senate voted to override the veto, as well. While conservation groups were glad to see the measure restored, legislative win came with the weight of grief.

“We’re excited for the policy. I think many of us wish that [Busch] would get to see the results,” says Alison Prost, executive director of the Chesapeake Bay Foundation Maryland, which worked with legislators to pass the oyster sanctuary bill.

Busch’s bill will come into effect beginning in July this year. Prost tells me: “His legacy will be in these five tributaries.”