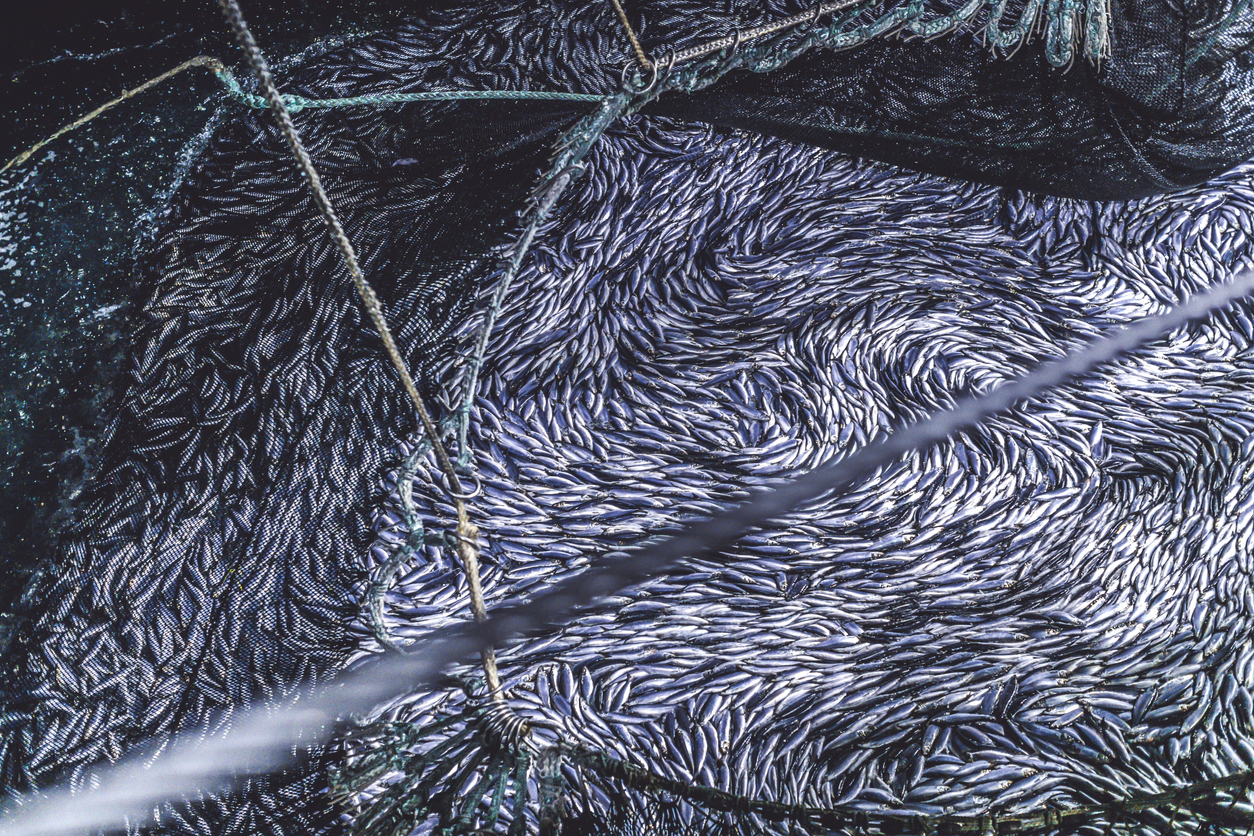

Photo / National Archives, Graphic / The New Food Economy

Prohibition turns 100 this week. The amendment sparked debate among doctors who saw alcohol as a cure.

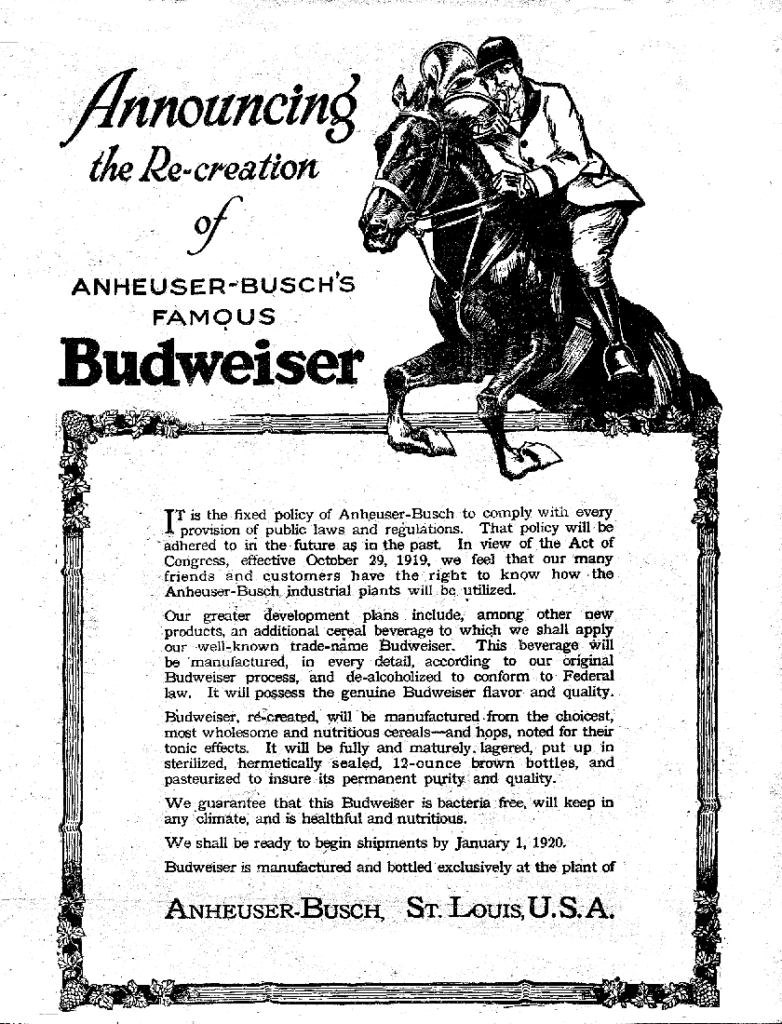

A hundred years ago this week, Prohibition went into effect across the United States. As the clock struck midnight on January 17, 1920, a newly-minted law enforcement agency called the Bureau of Prohibition was poised to begin raiding speakeasies and smashing beer barrels. At the same time, breweries were bracing for the blow: Budweiser had rolled out a “de-alcoholized” beer that was also, it claimed, healthful, nutritious, and “bacteria free.” It was the beginning of an era that lasted nearly 14 years until the repeal of the 18th Amendment.

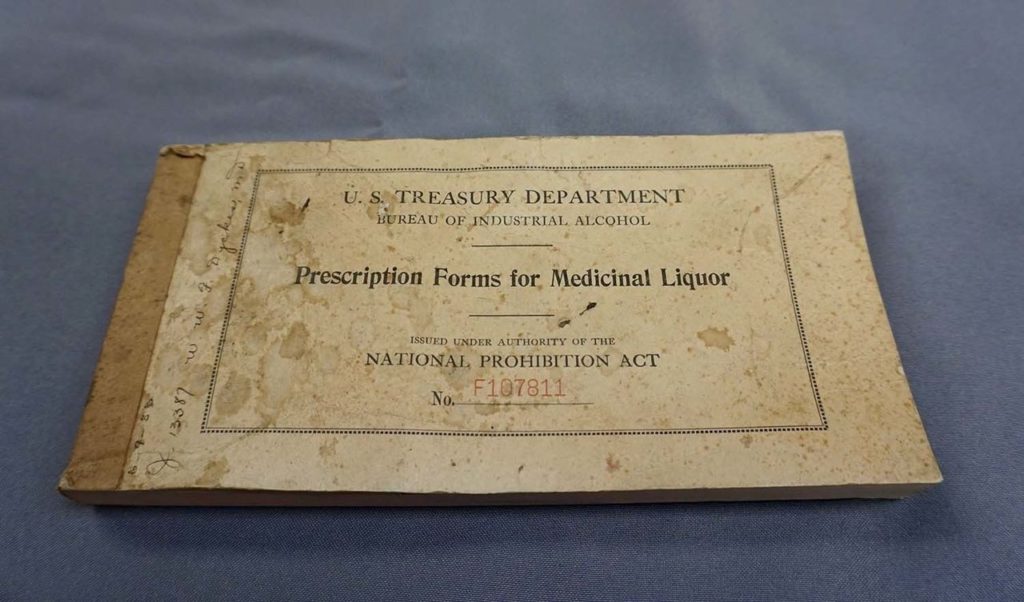

The Volstead Act—that’s the law that spelled out the enforcement of the eighteenth amendment—prohibited the manufacture and sale of alcoholic beverages. But it included two key exceptions: Religious leaders could store alcohol for use in worship, and doctors were allowed to prescribe booze as medicine. (Both carve-outs, predictably, saw their share of grift. As The New York Times noted in 2010, “sacramental wine was permitted, allowing fake clergymen to lead bogus congregants in nonreligious romps.”)

Official prescription pad for medicinal alcohol issued to Dr. W.W.F. Dykes, 1933

Melnick Medical Museum, Youngstown State University

To be clear, by the time Prohibition was passed, alcohol was not regarded by the medical establishment as a cure-all. In 1916, the American Medical Association had declared that alcohol’s use as a medicine had “no scientific basis.” In reality, though, it was still being used for just about everything. “Keep in mind that during this time period, there were very few effective medications for anything,” says Jacob Appel, a psychiatrist and historian based in New York City. In some cases, Appel adds, alcohol actually was the best available treatment. For example, he says, a cardiologist named John Davin in New York City “successfully” treated heart attack patients with beer. There’s no way that actually worked, of course, but at the time the standard treatment was long-term bed rest, which could lead to clotting and strokes. “The standard made them substantially worse and probably killed tens of thousands of people,” Appel says. “The people who got beer actually did much, much better.”

Once the Volstead Act went into effect, doctors’ prescriptions of alcohol varied widely. Winston Churchill, an enthusiastic tippler, was hit by a car when he was visiting New York City to give a lecture at the Brooklyn Academy of Music in 1931. He suffered minor injuries and was reportedly depressed for months. A doctor subsequently wrote him a prescription for a “naturally indefinite” quantity of alcoholic spirits to be consumed during mealtimes, specifying that Churchill should receive, at minimum, 250 cubic centimeters daily, roughly equivalent to 8.4 fluid ounces of hard liquor.

“The reality is that doctors walked around hospitals with shot glasses and flasks in the nineteen-teens.”

Medicinal alcohol was often written off as an easy source of profit for doctors and pharmacists during the Prohibition era. As Atlas Obscura reports, pharmacies in Brooklyn were charging up to $150 in today’s dollars for a pint of whiskey just weeks after the law went into effect. Physicians wrote an estimated 11 million prescriptions per year through the 1920s—a significant number, considering the country’s population at the dawn of the decade was just over 100 million.

But Appel argues generous prescriptions weren’t all about the money. Some doctors, particularly those in urban areas, took issue with Prohibition on moral grounds. They saw it as a discriminatory policy driven by Protestants in the heartland who were advocating to curb all kinds of “sinful” behaviors like drinking and gambling. Catholic immigrants in urban areas, by contrast, drank socially. “I think, for the most part, as far as we know, physicians were not … engaged in smuggling, in trading alcohol to profit themselves,” he says. “There were countless physicians who believed that Prohibition was basically designed to target ethnic Catholics in the United States. So they subverted Prohibition to … help their patients in what they thought was a benevolent and altruistic way.”

Other doctors—even those who supported Prohibition—saw efforts to limit alcohol prescriptions as an encroachment on the profession. If the government could tell them how to prescribe medicinal alcohol, the logic went, what would stop regulators from expanding their oversight even further? “This is one of the first efforts to restrict the rights of doctors to prescribe what they wanted to prescribe,” Appel says.

Budweiser had rolled out a “de-alcoholized” beer that it claimed to be, healthful, nutritious, and “bacteria free”

A hundred years later, medicinal alcohol is a thing of the past. But some of the central tensions from the medicinal alcohol movement have echoes in the current political wrangling over the legalization of marijuana. Like the 1920s, doctors are split on the clinical effectiveness of medical marijuana. Like the 1920s, some see medical marijuana prescriptions as a smoke screen for recreational use. And, like the 1920s, critics see the continued criminalization of marijuana use as a deeply discriminatory policy.

But Appel sees one key difference between then and now. In the 1920s, doctors went to bat for their right to prescribe alcohol. They formed alliances, lobbied Congress, and even took one case all the way to the Supreme Court. “I expected, in the nation’s nascent medicinal marijuana movement, for physicians who work in fields where medicinal marijuana can be helpful to take the same position. To really sort of get their dander up and say, ‘this is an important fight,’” he says. “On the whole, that has not occurred.”

Appel says that on the whole, doctors’ passion for marijuana just isn’t as strong as it was for alcohol. “The reality is that doctors walked around hospitals with shot glasses and flasks in the nineteen-teens,” he says. “No one is walking around my hospital today with a joint in his pocket.”