New Food Economy | Photos: Gage Skidmore, Bipartisan Policy, and USDA/Preston Keres via Flickr

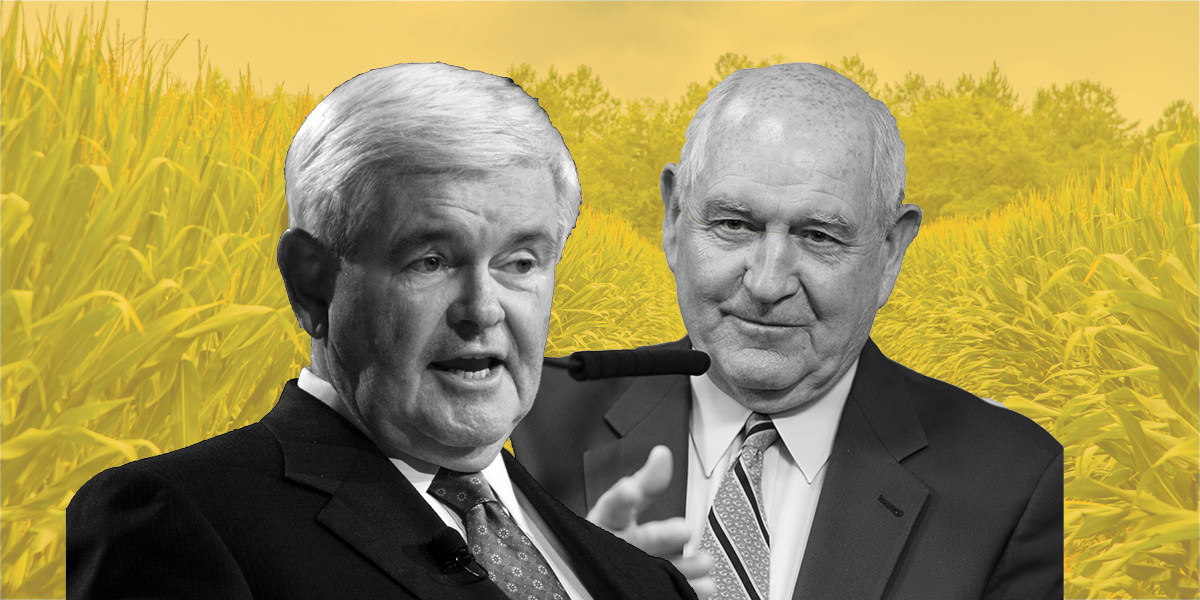

Last week, the Department of Agriculture (USDA) announced it would tighten work requirements for a large segment of food stamp users next spring—a move projected to kick 688,000 people from the nutrition program. Two days later, Secretary of Agriculture Sonny Perdue invited Newt Gingrich, one of the most vocal and longtime opponents of federal assistance, onto his podcast to underscore the Trump administration’s rationale for the move. Though politicians on both sides of the aisle have long advocated for “welfare-to-work” policies, arguing that they promote “self-sufficiency,” Perdue and Gingrich took the talking point one step further on Friday, suggesting that food stamp recipients conspire to stay unemployed and live off benefits alone.

“Americans are some of the most generous people, always willing to help out a neighbor in times of need, but at the same time—sometimes a helping hand can become an indefinitely giving hand, creating government dependency on programs like the food stamps program,” Perdue says in the episode’s introduction.

Gingrich agrees, adding later in the show that “there are some people, sadly, who believe that they’re being very clever if they can get their neighbors to take care of them.”

Sonnyside of the Farm is an official USDA podcast, which has aired every two weeks since its launch in October. (Not even the feds can escape the podcast bubble, apparently.) Each 20-minute episode kicks off with some banjo-heavy, down-home muzak, and features a conversation between the secretary and various public figures, focusing on the food and ag concerns du jour. Past guests include former White House press secretary Sarah Huckabee Sanders and talk radio host Max Armstrong.

Former House speaker Newt Gingrich is arguably one of the key architects of modern restrictions on government assistance programs. In 1996, Gingrich successfully lobbied to eliminate the Great Depression-era program that guaranteed benefits to all eligible families and replaced it instead with one that gave states block grants to distribute via benefits and services. Called Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF), the new program’s cash benefit recipients were required to work 30 hours per week on average, a number that varied depending on family composition. The Gingrich-led reform also instituted today’s limits on how long able-bodied, childless adults can receive food stamps—that is, three months out of every three consecutive years. Historically, states could apply for waivers to this requirement during times of economic hardship, but last week’s announcement will restrict their ability to do so. Gingrich sees this as a move in the right direction.

“If you start offering enough waivers, people who should be going to work are being told by the welfare office, ‘No, no, you don’t have to do that,’” Gingrich said. “And you begin to reshape the mind of the welfare worker because they begin looking for the loopholes that enable you to stay dependent on the government…. A generation that watches their parents do nothing learns that it’s okay to nothing.” (Gingrich didn’t respond to requests for comment.)

The picture Gingrich paints is a common trope in the political rhetoric around welfare programs, reminiscent of the derogatory “welfare queen” stereotype that President Reagan regularly evoked throughout his political career.

“The idea of dividing people who receive public benefits into the categories of people who are deserving and undeserving is a pretty standard playbook,” says Josh Levin, an author and journalist. In May, Levin published a book about the life of Linda Taylor, a woman who committed welfare fraud, among other wrongdoings, and whose story gave rise to the myth of welfare queens living large off of public benefits. A contemporary embodiment of the same narrative emerged last year in the case of the “Minnesota millionaire”—a man who claimed to have received $300 per month in SNAP benefits because he earned no income but had enough assets to be considered a millionaire. Both cases have been used by lawmakers to advocate for tightening SNAP rules.

But just how common is SNAP fraud? A single, nationwide statistic is difficult to pin down because there’s no standardized data collection among states which administer the program. However, just 3.4 percent of SNAP overpayment cases—that’s when a family receives more money than they were entitled to get—were linked to fraud by recipients. Most of these overpayments were due to a household or agency error, per a 2016 state activity report, the most recent year for which data is available.

“Just because one person commits fraud doesn’t mean that everyone is doing it or doesn’t even mean that it’s particularly prevalent, it just means that the program is capable of being defrauded,” Levin says.

Nonetheless, Perdue seems convinced that there are significantly more people on SNAP than those who need it, which explains his agency’s repeated attempts to restrict the program’s eligibility criteria.

“The numbers are stunning,” he says on “Sonnyside.” “In 2000, we had 17 million people taking advantage of SNAP benefits. That number rose during the recession up to over 44 million people. Now, with 3.6 percent [unemployment], more jobs than people seeking jobs, we’re only down to 36 million people.”

After gradually declining in the years since the 1996 welfare reform bill was passed, SNAP participation hit a low point in 2000, before rising again in the years leading up to the recession. Numbers then held steady until they began tapering off in 2015. But without context, such figures can obscure some harsh realities of today’s job market, particularly the difficulties in making ends meet through low-paying jobs. A 2018 analysis of Census Bureau survey data found that more than half of able-bodied, childless adults using SNAP in a given month worked during that month. It also found that three-quarters of them worked in the year prior or after they received benefits, and typically leaned on the program more when they were out of work. Some argue that officials ought to consider SNAP use within the context of the employment and economic circumstances that precede and succeed it.

“The analogy is: If I went to a hospital, and I saw somebody with a broken leg, and I thought, oh, that person has had a broken leg for their whole life, as opposed to having seen them before they broke their leg, and after they healed,” says Elaine Waxman, a senior fellow at the Urban Institute who conducts research on food assistance programs.

After Wisconsin instituted work requirements for able-bodied, childless adults in 2015, many residents simply lost their benefits, while just one-third of participants in a state welfare-to-work program ended up securing employment, as we’ve reported.

The Trump administration will likely move full steam ahead with its work requirement rule, which doesn’t need Congressional approval and will take hold in April 2020. Meanwhile, Sonny Perdue might get the last word—it’s his podcast after all.

“My experience working on the farm taught me the blessings of meaningful and purposeful work,” Perdue says. Then he adds: “I’m thankful I’m not still there today, handling all those watermelons and picking that fruit.”