A new report pokes holes in the notion that worker lifestyles are to blame for contracting Covid-19. Surprise surprise: The workplace is part of the problem.

Back in May, as Covid-19 tore through meatpacking plants across the country, public officials were quick to blame the people who worked at the plants for spreading the virus. In comments that were sometimes outright racist (a Wisconsin Supreme Court justice said a local outbreak wasn’t coming from “regular folks”), governors again and again blamed crowded living conditions and family gatherings for the spread of the virus among immigrant communities.

At the same time, worker advocates were arguing that employers had not followed through on promises to provide personal protective equipment and enhanced social distancing measures. It was a news cycle that struck many as patently absurd: Meatpacking jobs require workers to stand close together, in cold temperatures, using shared equipment. If employers weren’t even providing masks, how could workers be to blame?

New research from the Centers for Disease Control and the Maryland Department of Health indicates that, while foreign-born workers at two plants did contract Covid-19 at a higher rate than U.S.-born workers, risk factors contributing to the spread of the virus were more structural than behavioral. Based on interviews with 359 workers at two poultry processing facilities in Maryland in May of this year, the researchers found that immigrant workers were far more likely to work in positions associated with higher risk of virus transmission, namely in cold-temperature work areas and at fixed locations (as opposed to managerial or custodial positions that allow movement around the facility). The people who worked in positions that involved close proximity to others and the use of high-touch surfaces got sick at a higher rate than others.

While foreign-born workers were more likely to live in households with other poultry processing plant employees and more likely to commute with coworkers, they reported visiting fewer gatherings and businesses than U.S.-born counterparts, and more than 90 percent reported wearing masks during their commute.

Nothing about the behavior of immigrant workers suggests that they spread the disease in any way that was more than a product of their circumstances—the latter encompassing a set of factors the researchers refer to “structural” risks, as opposed to “behavioral” risks, which include activities like forgoing a mask or attending a potluck. While foreign-born workers were more likely to live in households with other poultry processing plant employees and more likely to commute with coworkers (both of which fall into the “structural” category), they reported visiting fewer gatherings and businesses than U.S.-born counterparts, and more than 90 percent reported wearing masks during their commute. The ultra-crowded living conditions evoked by elected officials weren’t borne out by the data, either: The average household size among immigrant meatpacking workers surveyed was 4; for U.S.-born workers, it was 3.

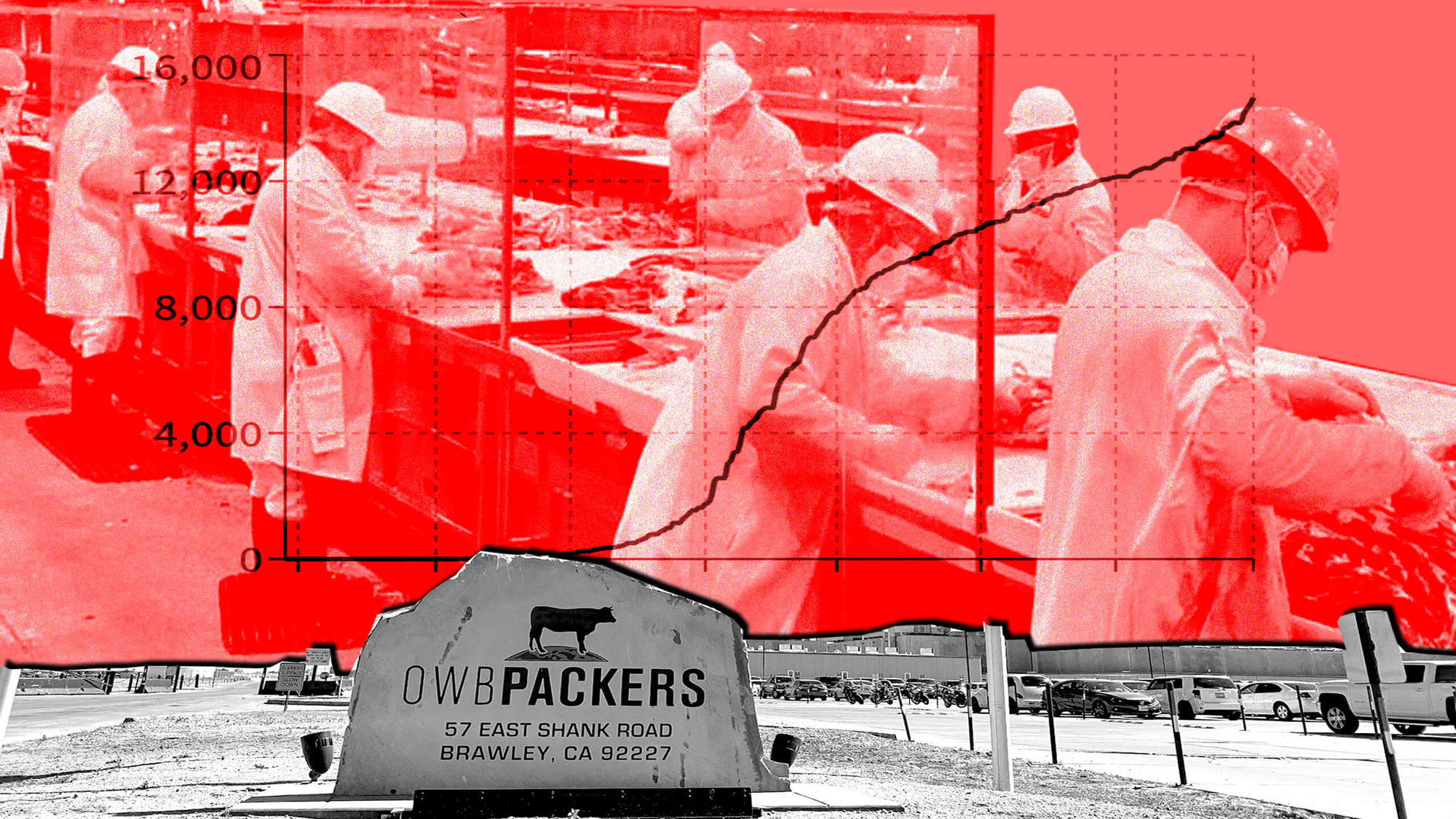

Though many meatpacking plants announced highly publicized virus mitigation measures after seeing huge outbreaks in the spring, workers continue to fall ill. According to the Food and Environment Reporting Network, more than 50,000 workers in the meatpacking industry have contracted the virus, and 262 have died.

The researchers concluded that meatpacking plants can do plenty more to mitigate the risk of spreading Covid-19 in the workplace. Better ventilation, physical barriers on processing lines, visual social-distancing cues, and staggered arrival and break times could all help minimize the spread. They also recommend that public health officials work to develop culturally and linguistically tailored messages to share information about minimizing risks in carpools and at home. (Not for nothing, the agency’s protocols would be difficult for anyone to follow: think sleeping with the window open and disinfecting the bathroom after every use).

Though the Centers for Disease Control has issued guidelines to meatpacking plants to prevent the spread of the virus, they remain voluntary. Enforcement of the worst workplace safety offenses remains spotty, even as infections continue to surge.