Researchers also linked pathogen data with different types of meat processing plants, suggesting that contamination might not happen only at the farm level.

Organic meat is half as likely to contain multidrug-resistant bacteria as conventional meat, according to a new analysis of contamination data collected from nearly 40,000 samples of chicken, pork, beef, and lamb, published last week.

This might not come as a huge surprise. Producers who market livestock as “organic” are prohibited from using antibiotic medicines that fight infection but also contribute to the alarming rise of drug resistance in both humans and animals. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), 2.8 million people contract infections that are resistant to antibiotics every year in the U.S., and 35,000 people die from them.

However, last week’s study didn’t just look at how different production methods are associated with contamination. It also raised a typically overlooked question: What role do middlemen in the meat supply chain—the facilities that process and pack the cuts of meat you see at the butcher shop or the grocery store—play in the spread of bacteria?

“There’s not a lot of literature out there on how the processing aspect of the food supply chain really impacts the consumer experience at the end of the retail store,” said Gabriel Innes, first author of the study and instructor of epidemiology at Rutgers University.

“Between organic and conventional meats, [split processors] have to do regulated cleaning. That regulated cleaning may be a great way to decontaminate as much as possible.”

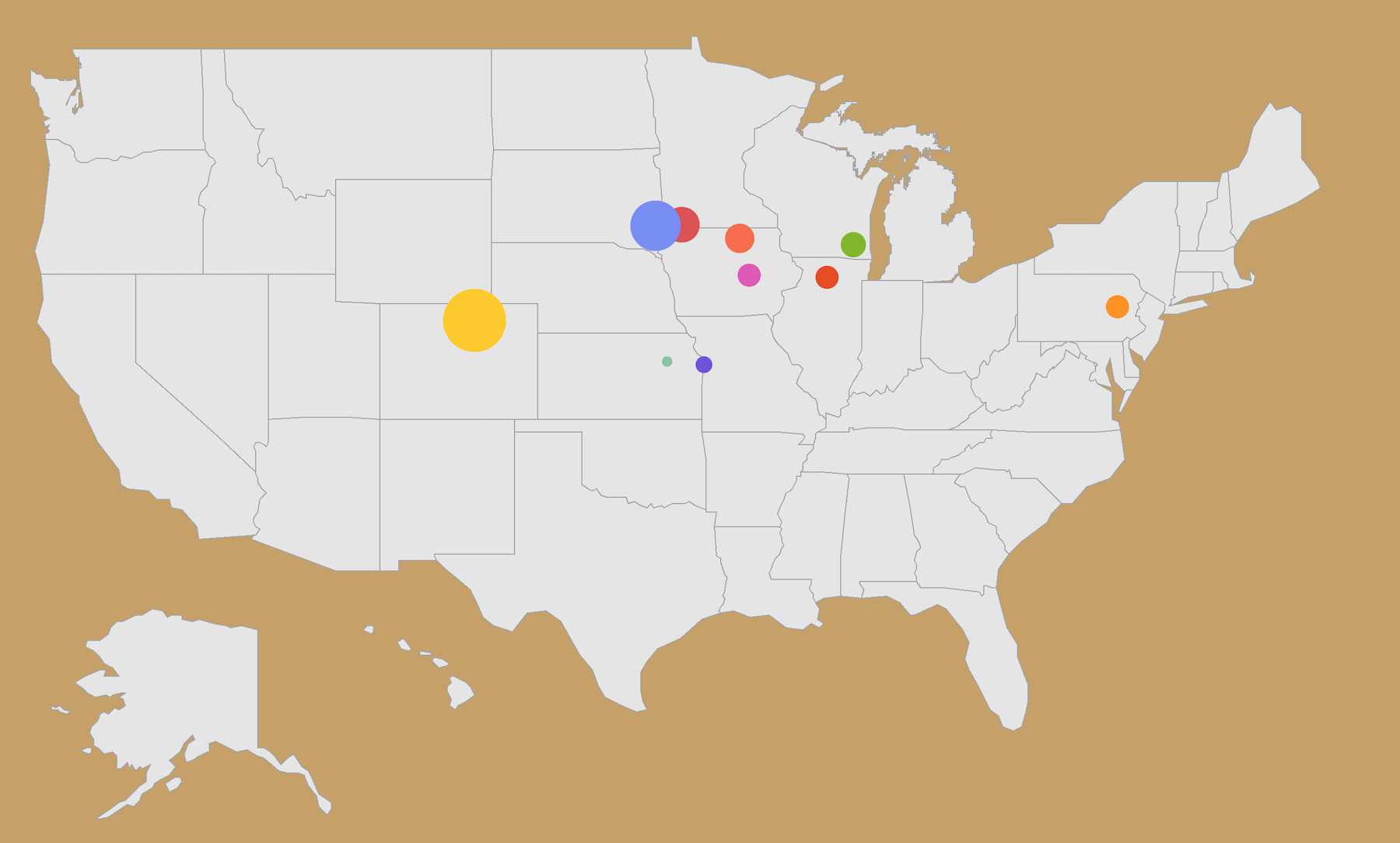

In their analysis, the report authors found the facilities that exclusively process conventional meat were significantly more likely to be associated with bacterial contamination of any type—drug-resistant or otherwise—when compared to plants that process both organic and conventionally produced meat, aka “split” processing facilities. Only one sample from an organic-only facility tested positive for any contamination. (However, it bears noting, meat from organic-only facilities made up a tiny fraction of the samples, so they’re not a strong data point from which to extrapolate broad takeaways.)

The findings suggest that stringent sanitation might be worth looking into as a strategy to mitigate the spread of antibiotic-resistant bacteria, which are the source of a major, ongoing public health concern.

Federal regulations require split processors to establish safety and cleaning plans that prevent organic meat from “commingling” with nonorganic meat. Innes hypothesized that those practices and buffers may be helping to prevent the spread of pathogens, as well.

“Between organic and conventional meats, [split processors] have to do regulated cleaning,” he said. ”That regulated cleaning may be a great way to decontaminate as much as possible.”

“[When] you’re on a slaughter line, you get very few breaks to go off and wash your hands.”

To conduct their analysis, the authors looked at five years of meat sampling data from the National Antimicrobial Resistance Monitoring System (NARMS), a federal program that randomly collects and tests meat from grocery stores for both the presence of bacteria and said bacteria’s ability to resist antibiotic treatment.

They found that meat from split processing facilities was 10 percent less likely to be contaminated with multidrug-resistant bacteria than from conventional-only facilities. The gap widened, however, when the researchers looked at all bacterial contamination, regardless of antibiotic resistance, finding that meat from split processing facilities was one-third less likely to be contaminated compared to conventional-only facilities.

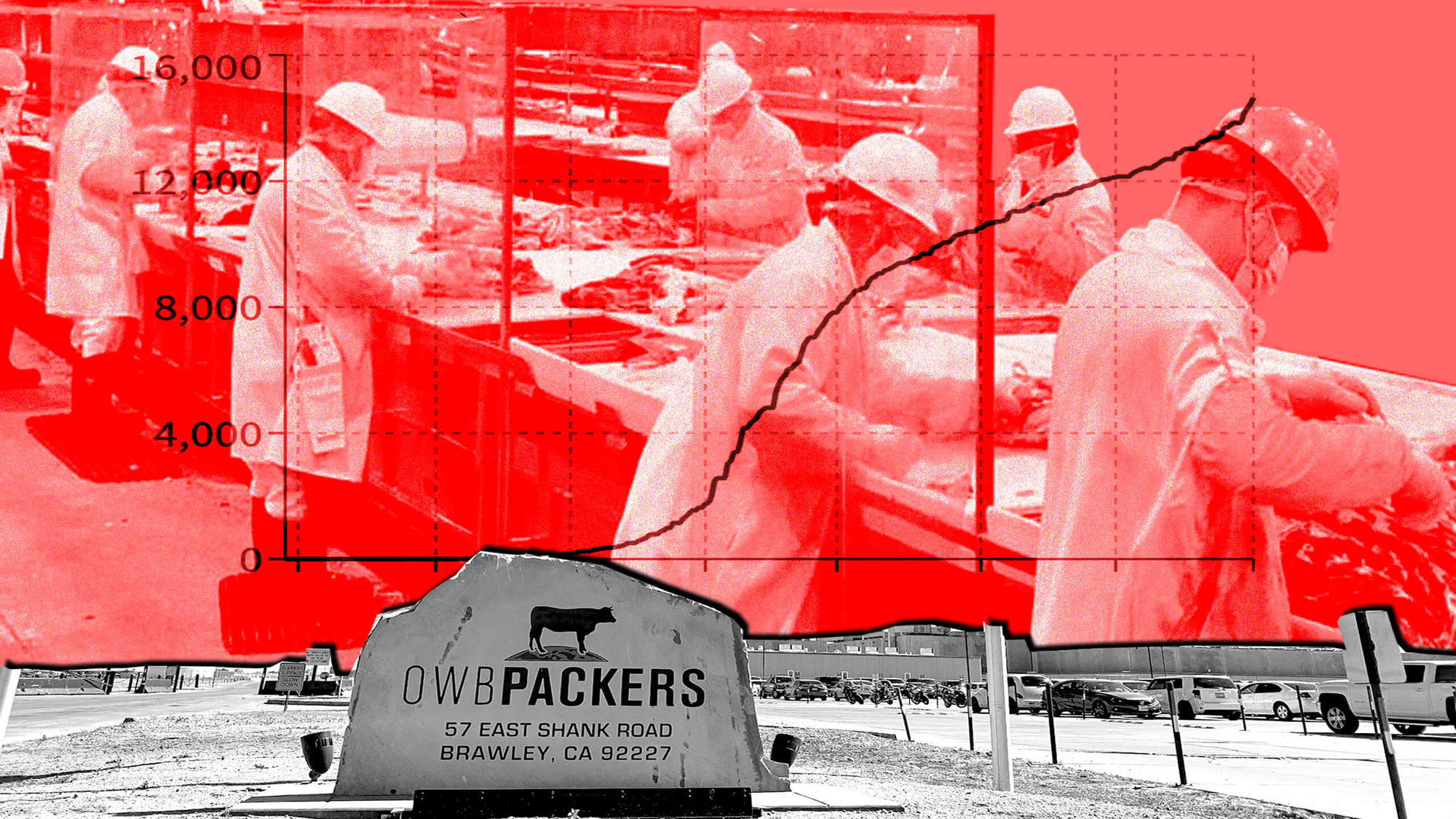

These numbers add to a growing body of research that helps explain how antibiotic-resistant bacteria makes its way from farms through the supply chain to eaters. And more research that tests meat for contamination at processing facilities—before they get to the grocery store, that is—could bring greater clarity to the unique occupational perils that farm and slaughterhouse workers face.

A study published in January found that swine farm workers are 15 times more likely to harbor a difficult-to-treat “superbug” known as livestock-associated MRSA, compared to people who don’t work with animals. Cattle workers are 12 times more at risk than the general public, and livestock veterinarians eight. Another analysis found that proximity to fields where swine manure is applied is associated with higher cases of MRSA. Public health experts have also argued that bacteria from animals poses an occupational hazard for slaughterhouse workers, as laceration accidents are frequent and open wounds can pose a high risk for pathogen exposure.

“If you have processes that are going to be associated with reduced contamination of retail meats, then that suggests that it may be possible to also have processes that protect the health and safety of the workers.”

“[When] you’re on a slaughter line, you get very few breaks to go off and wash your hands,” said David Wallinga, a physician and senior health officer at the Natural Resources Defense Council. “[Antibiotic-resistant bacteria] can be aerosolized, you can breathe it in when you’re breathing, you can get it on a finger and scratch your nose so very quickly you can get colonized.”

Not everyone who is exposed to antibiotic-resistant bacteria gets sick from it, and those who do may not fall ill until years down the line. However, as resistant bacteria becomes more common at a wide-scale, it can render medicine ineffective, making it harder to treat disease and illness globally. A 2017 World Health Organization report found that there simply aren’t enough new drugs under development that can combat increasingly prevalent pathogens.

The report authors hope that future research can drill down the specific factors that reduce multidrug-resistant contamination in different process plant environments, and that it informs sanitation practices industry-wide.

“If you have processes that are going to be associated with reduced contamination of retail meats, then that suggests that it may be possible to also have processes that protect the health and safety of the workers,” said Meghan Davis, senior author and associate professor at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. “Thinking about worker health more holistically is really important for us to address as we move forward.”