John A. Carlos II

Since 1947, North Carolina has been a right-to-work state, making it illegal to require union membership as a condition of hiring, and prohibiting collection of union dues from workers’ wages. These roadblocks have helped to energize workers to organize.

Pictured above: Eshawney Gaston on the megaphone in a Fight for $15 protest in North Carolina.

From a distance, it looks like a tent revival. Off a country road deep in Durham, North Carolina, dozens of people wearing white shirts gather under a large, white tent in an open field. There is singing, clapping, and even some dancing. People fan themselves in the thick and sticky July heat. Before long, a young Black man grabs a microphone and stirs the sweaty crowd onto their feet with a call and response chant.

“Everywhere we go

People want to know

Who we are

So we tell them

We are the workers

The mighty-mighty workers

Fighting for 15

Fifteen and a union”

The workers in question—food service workers, gig workers, Amazon drivers, and health care workers—came from across the state and as far as away as South Carolina to attend a “worker power” summit for low-wage workers new to NC Raise Up, the exceptionally active North Carolina chapter of the Fight for $15 and a Union—an advocacy organization demanding that corporations increase wages and that state and federal governments step in to mandate a $15 minimum wage. NC Raise Up began in 2013, and, since the pandemic began, the chapter has organized a dozen day-long strikes in the state. Most of these actions have been led by fast food workers, like the August 20 strike when workers employed at Freddy’s Frozen Custard & Steakburgers in Durham walked off the job and shut down the store during the lunch rush because of Covid-19 safety concerns.

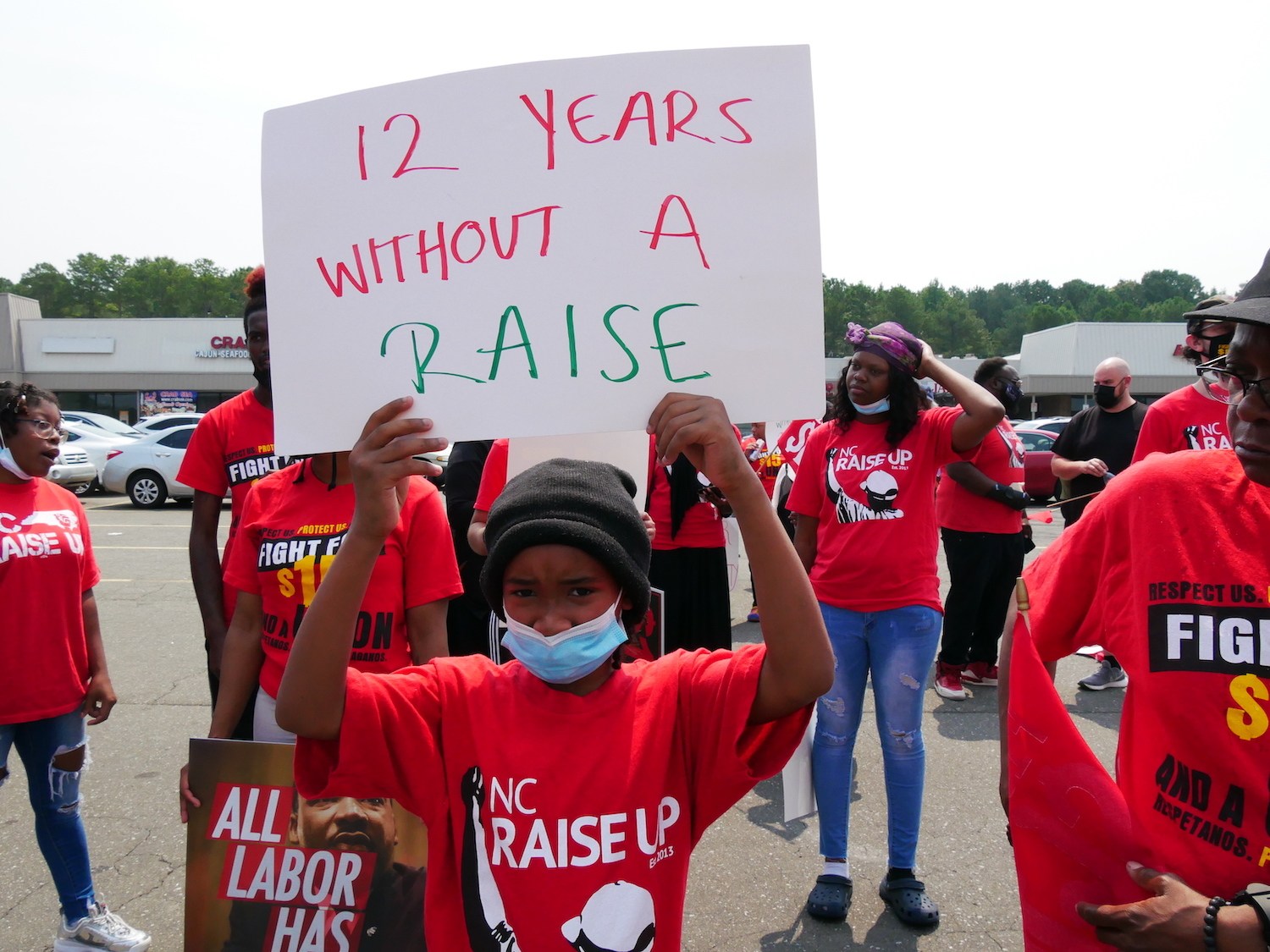

The workers in attendance at the July 24 summit weren’t just new to NC Raise Up; they were new to organizing and activism, new to thinking of themselves as being part of a labor movement. Just four days earlier, on July 20, NC Raise Up’s greenest members participated in their first ever strike to mark 12 years since the last time the federal minimum wage was increased. This included young people like Mathew Honeycutt, an 18-year-old father who makes $9.50 an hour pulling 16-hour days at an Arby’s in Kannapolis, North Carolina. Over lunch at the worker summit, Honeycutt explained that while he was relatively new to the Fight for $15, he already felt at home.

Attendees new to NC Raise Up, the exceptionally active North Carolina chapter of the Fight for $15 and a Union, gather in Durham, North Carolina.

Fight for $15

“I feel at peace,” he said. “I’m not leaving this organization. It helped me understand it’s not just me in this battle.”

Courtesy of Mathew Honeycutt

Mathew Honeycutt, 18, makes $9.50 an hour working 16-hour days at an Arby’s in Kannapolis, North Carolina.

Honeycutt works 80 hours a week, but he often cannot afford to pay all of his bills or to put food on his family’s table, let alone buy a car or have a place of his own. Simply put: He is tired of working his young life away and having little to show for it. This was part of his impetus for joining NC Raise Up. Prior to becoming a member of the organization, Honeycutt didn’t know he had the right to strike or organize his workplace. He didn’t know he could fight back against unsafe and unsustainable working conditions until—like many other members of the Fight for $15—he was recruited to join by a coworker.

The “battle” Honeycutt was referring to is life as a low-wage worker. In the U.S., 44 percent of all workers—53 million people—earn low hourly wages, meaning they live below 150 percent of the federal poverty line, or about $36,000 for a family of four. These are the working poor whose paychecks do not generate enough income to provide even basic necessities—and conditions are even worse in the fast food industry, which makes up a bulk of NC Raise Up’s membership. Eighty-seven percent of fast food workers—more than twice the rate of the general population—don’t receive any health benefits. Around 70 percent of people on the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) and Medicaid work full-time for large corporations like McDonald’s, which is among the companies with the most workers on federally-funded programs. In fact, instead of raising wages, McDonald’s encourages its workers to sign up for these benefits.

“Mentally, it’s really hard to go to work every day and know your workplace doesn’t care about you as a person,” Honeycutt said. “But now I have a family in the Fight for $15 and a Union. There are a lot of people standing up in North Carolina right now and trying to make a difference. This really gives me hope that I won’t always have to be in survival mode.”

“Mentally, it’s really hard to go to work every day and know your workplace doesn’t care about you as a person. But there are a lot of people standing up in North Carolina right now and trying to make a difference.”

The stakes are high for the thousands of workers across North Carolina who have invested their little free time into NC Raise Up. The poverty they experience literally makes them sick, and they are one paycheck away from further catastrophe, as some already struggle with housing instability. In July, The Counter attended NC Raise Up’s worker summit because we wanted to know: What does it look like on the ground when organizing a multigenerational, multiracial and multiethnic labor movement in a heavily segregated state with some of the most anti-worker laws in the country?

It’s not easy, the workers say, but poverty wages and unjust conditions are no longer an option.

Political education in a right-to-work state

North Carolina consistently ranks as one of the top states in the nation for businesses, but what’s good for businesses doesn’t correlate with good working conditions.

Since 1947, North Carolina has been a right-to-work state, which means it is illegal to make union membership a condition of being hired and it is prohibited to collect union dues from workers’ wages. According to the Institute for Southern Studies’ publication Facing South, the roots of right-to-work laws are in the Jim Crow South, where anti-Black and antisemitic Southerners and their Northern allies worked to maintain an economic system “built on racial division and cheap labor.” Therefore, anti-union measures were meant to “prevent what industrialists and planters in both the North and South saw as interracial organizing’s threat to the racial and economic order.” Right-to-work laws greatly limit the power of labor unions, so it should come as no surprise then that North Carolina consistently has one of the lowest union membership rates in the country. Making matters worse, the state Department of Labor is known for safeguarding employers more than workers, which has been especially disastrous during the pandemic.

Clermont Ripley is the co-director of the Workers’ Rights Project of the North Carolina Justice Center, a progressive research and advocacy organization. She told The Counter that North Carolina’s anti-union history has led to a great deal of misinformation and misunderstanding about what is and isn’t legal.

“A lot of people think it’s ‘illegal’ to unionize here, but it’s not.”

“Living in a right-to-work state doesn’t mean that you can’t be in a union or engage in collective bargaining,” the attorney explained. “Right-to-work is a purposefully misleading name with a lot of legal complexities, but at the end of the day what it really means is that everyone who is eligible to be in the union does not have to be in one. Here in the Southeast where we have a really racist anti-union history, the government and employers go out of their way to make sure that unions are as weak as possible—and that includes disseminating misinformation. A lot of people think it’s ‘illegal’ to unionize here, but it’s not.”

It is because of these roadblocks that North Carolina’s chapter of the Fight for $15 and a Union is one of the most active in the nation. Workers in the state are tired of these working conditions and fighting to change them—and they know that a $15 minimum wage isn’t enough. As one worker at the summit said, “None of the problems we have at work will go away just if we get paid more; that’s why we need a union.”

As part of its curriculum for new members, NC Raise Up focuses heavily on political education to combat misinformation in the state. Like Matthew Honeycutt, fast food workers who spoke to The Counter said that before joining the organization, they had no idea what their basic rights were in the workplace. They assumed it was a given that any organizing could lead to immediate termination, or that getting called “sweetie” and being touched by a manager was simply another part of the job they had to endure.

One of the most striking moments at the day-long worker summit in July was during a workshop where a beloved longtime Fight for $15 member who goes by the name Mama Cookie gave an impassioned speech to fast food workers about the different forms that sexual harassment can take in the workplace.

Mama Cookie, 52, is a longtime Fight for $15 member.

Courtesy of Mama Cookie

“It looks all different kinds of ways; it’s not just touching,” Mama Cookie said. “It’s the way they talk to you, it’s the names they call you. It’s them crowding your space.”

You could see realizations flashing across their faces, and multiple workers shared traumatic experiences with workplace sexual harassment.

Mama Cookie, who is 52, says this is why education is important. Even though people of all ages have to take exploitative low-wage jobs to survive, she said no one ever tells them how to navigate abuse or what recourse they have if their rights are violated.

“Employers don’t want people to know their rights in the workplace,” Mama Cookie said. “They want us in the dark. If you are working for $7.25 it’s because you really need that $7.25 and they count on your silence, but we can’t be silent anymore. That’s why you have to know your rights, without knowledge, you don’t have anything. You don’t have a leg to stand on.”

“We all need to be complaining together”

Workshops for new NC Raise Up members are geared toward getting fast food workers to open up about their experiences in the workplace and to recognize their points of connection with other workers. In one exercise, attendees formed a circle and every time an organizer read a quote that resonated with them, they stepped inside the circle.

I’ve been called essential, but I’ve not been treated as such.

I have to work two jobs because I’m not paid enough.

I want healthcare, but my job doesn’t offer me any affordable options.

I struggle to pay my bills every month.

Working during Covid has taken a toll on me.

No matter their industry, age, race, gender, or ethnicity, every worker in the room stepped forward. Some shared stories about why these statements resonated with them, relaying stories about family members dying from Covid, health insurance that would have eaten their entire paycheck, pulling doubles and triples and still being unable to make rent, or co-workers threatened with termination if they did not show up to work when they were sick.

Getting workers to share their personal experience is one thing, but helping them link their oppression to other forms of oppression is another. Fight for $15 organizers routinely tell new and prospective members that racial justice and economic justice are inextricably linked, but this can be a hard conversation to have with rural white workers uncomfortable with discussions about race. But there’s plenty of data to prove the point.

NC Raise Up, the exceptionally active North Carolina chapter of the Fight for $15 and a Union—an advocacy organization demanding that corporations increase wages and that state and federal governments step in to mandate a $15 minimum wage.

Fight for $15

The economic benefits of raising the minimum wage from $7.25 to $15 an hour are well documented—notably it would lift the wages of nearly 40 percent of Black workers, the Economic Policy Institute reported, and help to reduce the racial wage gap. Poverty is also one of the most significant social determinants of health and mental health, the Psychiatric Times reported, and low-wage workers who are women of color experience poverty in disproportionate numbers.

Black workers—and specifically, Black women—made up a majority of the attendees at the worker summit, and this is the same population who are growing the movement. Eshawney Gaston was recruited to join NC Raise Up in 2017 by a McDonald’s co-worker, who invited her to a worker summit that was happening in Atlanta, Georgia. The 22-year-old said it’s been an “eye-opening” experience that has changed the course of her life. She has helped to organize her fast food restaurant, has brought new workers into the organization, and she is now considered a worker-leader in the movement.

“When my nieces and nephews call me and say they saw me on the news at a protest, that means a lot to me,” Gaston said. “Being a worker-leader is one of the greatest things that has ever happened to me. Before the Fight for $15, I wasn’t into politics and I never thought about activism. But now my co-workers know they can rely on me to fight for them and I have a role to play in my community. Activism is going to be in my life forever now because it gives me the power to change things.”

Eshawney Gaston, 22, was recruited to join NC Raise Up in 2017 by a McDonald’s co-worker.

Courtesy of Eshawney Gaston

NC Raise Up is a worker-led movement, which means it takes direction from a steering committee of low-wage worker-leaders in fast food, retail, health care, and service industries who meet monthly to discuss issues in their communities and workplaces. These meetings don’t just lead to protests. In the earlier days of Covid, when workers’ hours were cut and their families went hungry, the steering committee created a food pantry that is still feeding workers today.

Mama Cookie, who is a member of the steering committee, told The Counter that given the racial and ethnic makeup of NC Raise Up, creating a cohesive movement that organizes workplaces can be challenging—especially when it comes to conversations about race. “You don’t always know how people will react,” she said, but so far she hasn’t experienced any major issues.

“It’s the same thing between younger workers and older workers or Black workers and white workers—there are challenges, but we can learn from each other,” Mama Cookie said. “Young white workers ask me how I’ve survived everything I have in the workforce and that opens up a conversation. I ask them about their families and about their lives and we find out that we have a lot in common and that what we are learning in this movement is something very different than what they were taught and how they were raised to be.”

But the life-long fast food worker also said that it’s time for white and non-Black people of color to join the fight for workers’ rights in North Carolina.

Mama Cookie teaches about wage exploitation to fellow NC Raise Up workers.

Courtesy of Mama Cookie

“I feel like for a long time with this movement, they would see us out in the streets and think, ‘Oh, that’s just Black people complaining,’” she said. “But you know what? Now we got white people complaining and Latino people complaining and all kinds of people because there’s a lot to complain about and we all need to be complaining together.”

Seventeen-year-old Camila Cardoso, who started working in eighth grade to help support her family, quit her McDonald’s job just before the worker summit. For a while, she was juggling that job and another at Marshall’s while attending high school full-time. Cardoso was one of the only Latinx workers at the summit, and in workshops it was important to her to remind other workers that whatever their advocacy in the state accomplished, it would likely leave behind wide swathes of the state’s more than 300,000 undocumented immigrants. Cardoso comes from an immigrant family. She told The Counter she’s in the Fight for $15 for the long haul and she wants to bring migrant workers into the movement.

“A lot of people in our community, including my parents, come here with this idea of the American dream, but in reality they just work non-stop and juggle three jobs,” Cardoso said. “As a first-generation kid, I feel this responsibility to help and make things better and for me, it’s not just about me making $15 an hour. It’s about wage theft that happens to our gente, and it’s about language justice and problems that impact undocumented people. These are the issues I want to connect to Fight for $15.”

“As a first generation kid, I feel this responsibility to help and make things better and for me, it’s not just about me making $15 an hour. It’s about wage theft that happens to our gente, and it’s about language justice and problems that impact undocumented people. These are the issues I want to connect to Fight for $15.”

Every worker The Counter spoke to had a different motivation for joining the movement and helping to sustain it—even though progress has been slow and it’s tough for workers to juggle regular organizing meetings with the everyday stressors of being low-wage workers during a pandemic.

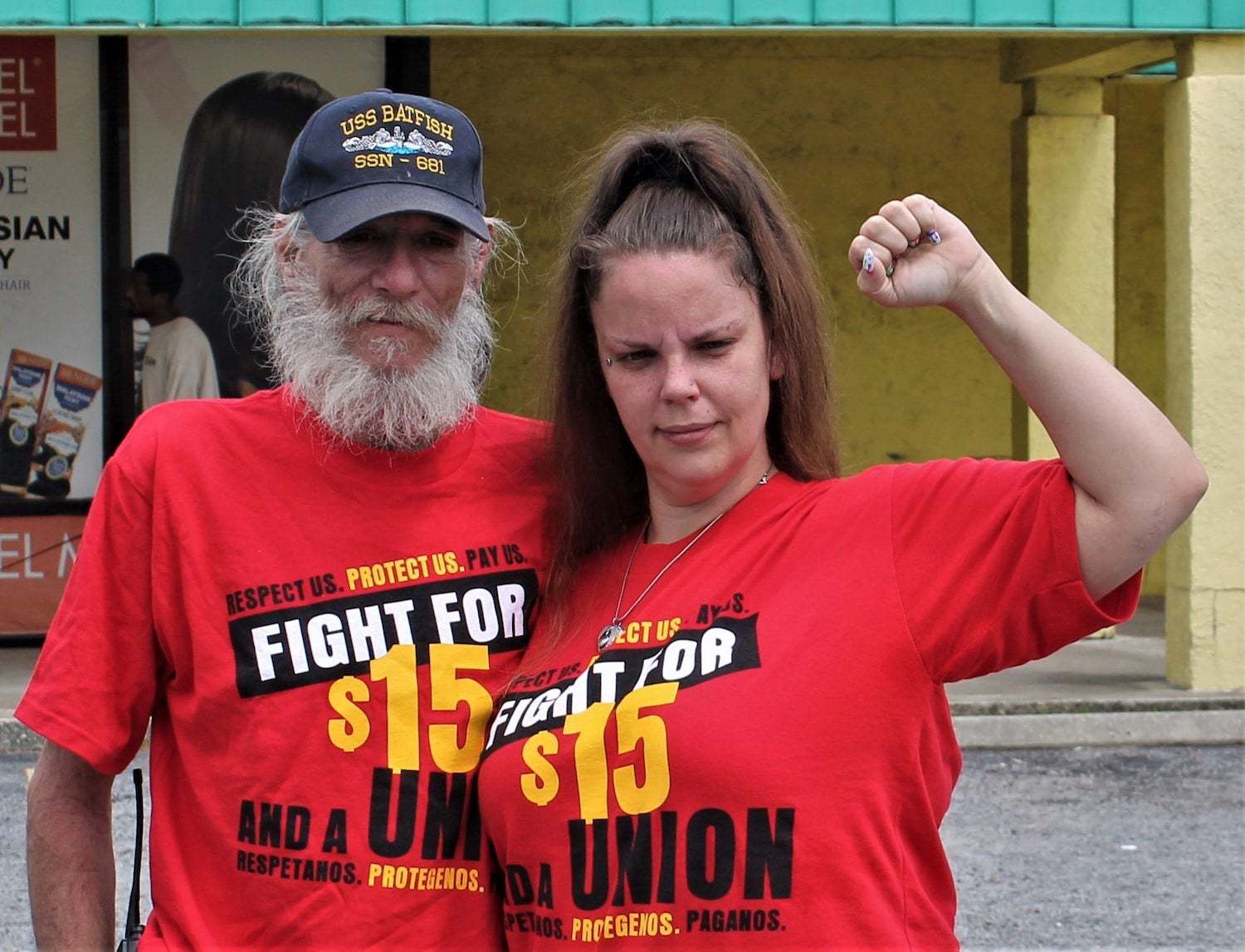

Beth Schaffer is part of a Charleston, South Carolina crew of workers who are in NC Raise Up because South Carolina doesn’t have a chapter of its own. Schaffer is a tipped worker employed by the Red Crab Seafood chain where she makes $2.13 an hour, plus tips. This essentially means that the 37-year-old lives off of her tips and even though she works 80 hours a week, she can’t afford an apartment of her own.

At Red Crab, patrons routinely drop hundreds of dollars on expensive seafood, but Schaffer said most don’t tip even 15 percent. During the summer, it’s not been unusual for her to make just $60 for a full day’s work.

Beth Schaffer (right), part of a Charleston, South Carolina crew of fast food workers, and her dad (left), at the strike on July 20.

Courtesy of Beth Schaffer

Schaffer has been in the Fight for $15 since 2014 and says she’s committed to the cause because “doing nothing doesn’t help anybody.” But little about her life circumstances have changed since she joined. In fact, the worker-leader couldn’t afford to take time off work to attend the summit in Durham. Her father, a slight, elderly man with a bushy white beard, showed up on her behalf. He listened intently during sessions, though mostly kept to himself, spending breaks in between sessions swaying in a rocking chair, smoking, and listening to southern rock.

The server doesn’t blame the lack of progress toward a $15 minimum wage on the movement—after all, there is only so much that workers can do on the ground, Schaffer said. At the end of the day it’s on government officials to move the needle toward a livable wage, and elected officials are failing millions of low-wage workers.

Schaffer said what keeps her in the fight is two-fold: her hope for a better future for low-wage workers, and her anger.

“It makes me angry that people don’t understand that we live paycheck-to-paycheck. There isn’t a day that goes by where I don’t worry about making rent or being able to put food on the table,” she explained. “It’s been a really, really long struggle, but what keeps me hopeful is how many people are joining this fight right now. We are tired. We’re sweating and slaving for these corporations that make billions of dollars and give us nothing, but I know we have power and I know that power is growing. I believe that we will win.”