The Supreme Court on Monday began hearing oral arguments in what labor observers are saying could be the most impactful case in decades.

At the heart of Mark Janus v. American Federation of State, County, and Municipal Employees, Council 31 is a question about who should support labor unions. Just the dues-paying members, who’ve elected to join? Or should other workers who benefit from their services, but aren’t members, have to pay fees, too?

We’ll get to the food peg in a moment. Members of the Service Employees International Union (SEIU), which represents food service workers, you’ll want to read on.

The dues question is complicated. The plaintiff in this case, Mark Janus, works for the state of Illinois as a child-support specialist in the Department of Healthcare and Family Services. Janus, like many public-sector employees, pays dues for the services of a union called the American Federation of State, County, and Municipal Employees (AFSCME), to represent him during contract negotiations and issues relating to wages, hours, and other aspects of employment. But Janus did not actually elect to become a member of that union. So the $45 that comes out of his monthly paycheck to pay for those services aren’t actually dues, but “agency fees.” Terminology notwithstanding, the key here is that Janus pays for AFSCME services by default, not by choice.

Janus’ legal team is arguing that those fees are actually a form of speech. And because he works for the state of Illinois, they say being forced to pay union fees is like the government forcing him to say something he doesn’t agree with. Compelled speech is a violation of his First Amendment rights.

Put simply, unions don’t just represent people. They represent ideas and beliefs. And paying dues, at least in theory, would indicate you support things that unions do and stand for, like collective bargaining, organizing more workplaces, and donating to politicians. Janus has indicated he doesn’t think collective bargaining is necessary. So why should he pay for something he doesn’t believe in?

Based on how the first day went, Janus is likely to win that argument, by a 5-4 vote.

AFSCME, along with three other public-sector unions, including SEIU, issued a joint statement after the oral arguments, condemning the case as a front for wealthy conservative donors who are funding Janus’ legal team. “We stand united in fighting a rigged system that rewards the super-wealthy at everyone else’s expense,” said Lee Saunders, president of AFSCME, in a statement.

If Janus wins, this could be a crushing blow to organized labor. First and foremost, unions that represent public-sector workers, like AFSCME, SEIU, and teachers’ unions, stand to lose revenue and members if more workers like Janus opt out of paying fees. Twenty-eight states already prohibit unions from charging agency fees via the “right-to-work” law. Wisconsin, for example, saw a 24 percent decline in union membership after it passed that law in 2015, according to the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Janus could open the door to every state in the country becoming right-to-work. Unions could be forced to retrench, focusing more on retaining members in shops where they already have a presence, as opposed to adding more, and organizing new workplaces.

“What we’ve seen is when right-to-work laws pass, union members often decide they don’t want to pay their union dues—not understanding the impact that that will have on jobs in total, not just on a personal dues payment, but also the effectiveness of collective bargaining,” says Amity Paye, a spokeswoman for SEIU 32BJ, which represents building service workers. “It can undermine the work of the union if everyone isn’t paying their fair share.”

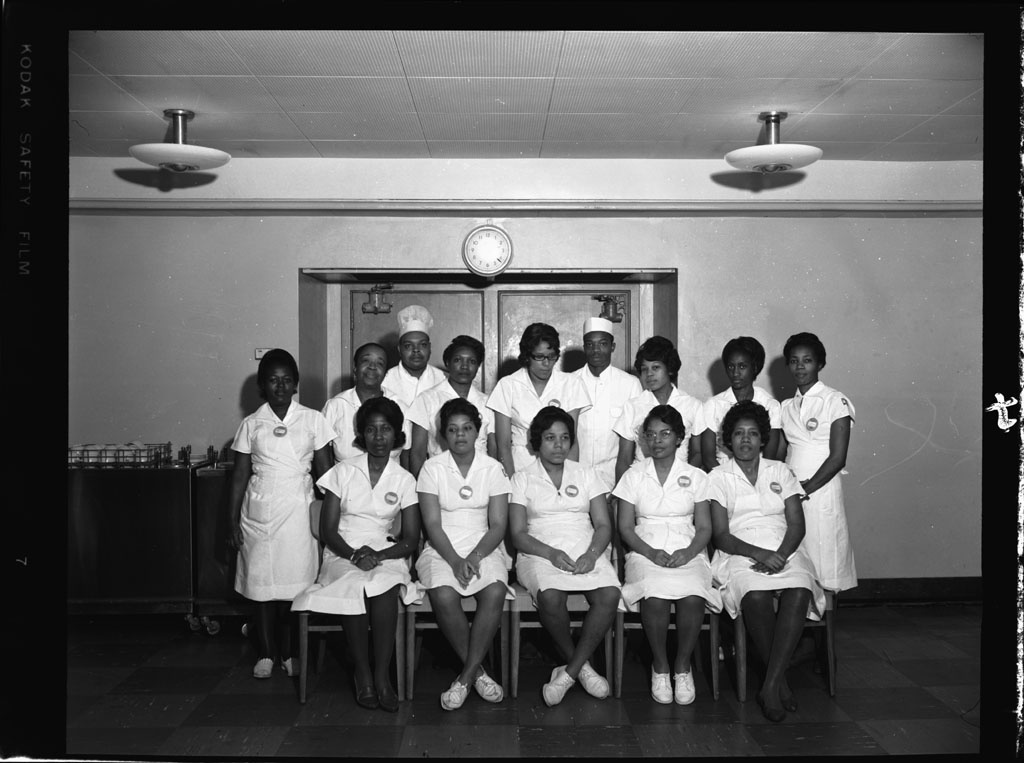

Drained revenue and membership declines aren’t just bad for unions as a political entity, but arguably, for workers, period. Nationwide, public-sector workers represented by a union earn around 20 percent more than their non-represented counterparts. Losing those jobs could have a devastating, if long-term effect on workers, particularly black women, who represent the highest share of workers in the public sector, according to an analysis by the Economic Policy Institute.

Plenty of those public-sector jobs are in food service. Think of food cart vendors at national parks and zoos, cooks at Army mess halls, and tens of thousands of cooks and cafeteria workers in grade schools, universities, hospitals, and prisons. Union food service jobs are often more than that. They can be stable careers.

Cafeterias in state institutions have historically been a beachhead for unions. According to Francis Ryan, a labor historian at Rutgers University, AFSCME was in state hospitals as early as the 1930s. In the 1960s, along with the SEIU, it began organizing in cafeterias in universities and municipal government buildings, in an era known as public sector’s “new militancy.” As part of campaigns to organize the whole institution, from clerks to crossing guards, AFSCME was bringing in as many as 1,000 new members a week by 1967.

But that “remarkable” rate fell in the 1970s, Ryan says, with a loss of federal money for public institutions. The decline hamstrung public-sector unions. First, it limited the ability to demand higher wages and benefits. Second, with less federal money available, state institutions began shedding their ranks, and hired contractors to staff up their buildings instead. Today, state and government cafeterias are a mix of traditional public-sector employees and subcontracted counterparts working for corporations such as Aramark and Sodexo. Unions represent both groups, and they say the Janus ruling, even if it doesn’t apply to the subcontracted workers, will effect both.

“Public and private workers have always raised standards for one another. If Janus were to weaken public school workers’ collective bargaining power, it could hurt contracted food service workers too,” Gabe Morgan, a vice president at 32BJ, said in an email to the New Food Economy.

Ryan says unions like SEIU and AFSCME have had some success in organizing subcontracted government workers, but in general, “it’s difficult to crack that nut.” That’s because contract jobs are typically less lucrative than traditional employment. In the case of public universities, cooks who work for concessionaires, and not the university, tend to earn lower wages and have fewer benefits. That makes the job less attractive to people who are looking for careers, or trying to raise families, and more attractive to someone like a student, who might see a cafeteria job as a way station. When the ranks churn like that, unions struggle to gain a foothold and some stability.

Generally speaking, low wages, meager benefits, and high turnover are the case in any food service job. That’s why the sector, as a whole, boasts only around a 3 percent union membership rate, making it one of the very lowest in the country.

Those are the conditions that unions like SEIU have strived to change, primarily by throwing their weight behind legislation, like fair workweek laws and the $15 minimum wage, that make jobs resemble something more like careers. Aside from pushing legislation, SEIU and other food service unions might be able to ramp up membership by trying to organize individual shops. But that’s costly. It forces unions to pay organizers to dig in, even as the workers come and go. A restaurant here or there is a long shot, but something that SEIU, and others like it, might be in a position to do if they had more agency fees coming in.

A decision on Janus is expected in June.

Disclosure: The writer’s father is a partner at a law firm that represents AFSCME Council 31, though not in this case.