Agricultural productivity in the breadbasket of America—the Midwest—could drop 25 percent or worse by mid-century without a miracle in technology, says the 2018 National Climate Assessment dumped by the White House along with the turkey carcass on Black Friday.

President Trump said he did not believe the report, required by law every four years. But many Iowa farmers do, after a harvest delayed by five- and seven-inch September rains back-to-back in a week, by uncommon molds and grain toxins, and by spotty yields wrought by freak weather.

People who depend on the weather and hawk its signs every day know it’s getting wetter, warmer, and weirder, and have recognized it for some time.

“How do you expect 200-bushel-per-acre corn with sandy topsoil?” asks Dr. Jerry Hatfield, director of the United States Department of Agriculture’s (USDA) National Lab for Agriculture and the Environment in Ames, Iowa. He authored the section on agriculture with Dr. Gene Takle of Iowa State University. Takle shares a Nobel Prize for climate modeling.

As the torrents sweep across the Tall Corn State, farmers have increased the vast underground drainage tile system in the flat glacial loam of northern Iowa by fully a third since 1980. We move water away faster than ever to the rivers and deprive the aquifers of that leachate.

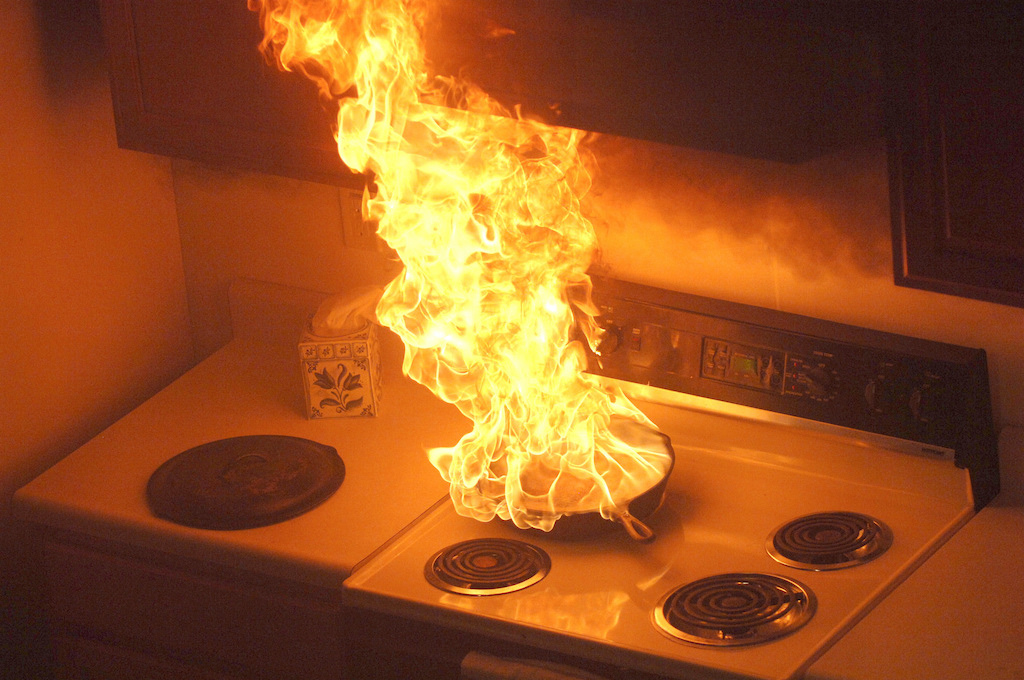

The soil- and fertilizer-rich water is washed down the Mississippi River to the Gulf of Mexico, where phosphorous and nitrate create a dead zone of oxygen deprivation the size of New Jersey and growing. It is suffocating the fishing industry.

NASA

NASA Dead zones, like the massive one in the Gulf of Mexico, are areas of water that are no longer life-sustaining due to oxygen deprivation linked to runoff from farms

Climate change already is causing Nebraska and Kansas to compete for the Republican River. It caused the Des Moines Water Works to sue three Northwest Iowa counties unsuccessfully for drainage system pollution of the Raccoon River, from which the capital metro drinks. And it is stressing cattlemen on the Great Plains amid a decade of drought.

The rains are coming heavier every year in Iowa. The average maximum rainfall around Cedar Rapids has increased 50 percent since 2000, Takle notes. Those extreme rains cause massive flooding in Des Moines and Cedar Rapids. And they drowned many planted fields in northern Iowa and southern Minnesota last summer as gushes would overwhelm swaths of the region yet leave others in a sweet spot. Storm Lake, in Northwest Iowa, saw corn yields of 200 bushels per acre. Ten miles north, yields were half as much.

“It’s the new normal,” says Takle.

2018 is on pace to be the wettest year in state history.

Protein content in No. 2 yellow corn is declining because of soil degradation from farming up to the riverbanks in a chemical base that packs more corn plants into an acre every year, says Iowa State agronomist Dr. Rick Cruse. He notes that wheat production in China already is declining because of warmer temperatures and poorer soil.

Takle also worries about warmer temperatures, and longer hot-dry spells, hitting right at pollination time in July. That can kill a corn crop.

“It’s a scary prospect,” Hatfield says. “Those heat waves are the fastest way to kill a crop that was destined to be profitable.”

Twenty to 30 percent of Iowa’s farmers are said to be under tremendous financial stress after six straight years of net losses on their corn-soy-ethanol culture. Trade wars shaved $2 off the price of a bushel of soybeans this year. Disaster payments won’t make them whole. Meanwhile, the cost to dry all that wet corn this year puts the farmer even farther behind.

Ultimately, Nature will demand that we heel to it. We are feeling it now whether the president wants to believe it or not

The report notes that there are solutions. Hatfield and Takle think the Midwest needs a landscape change with conservation efforts on every acre, year-round. More cover crops in winter, more grass and cattle on pasture and fewer in red-dust feedlots. More crop diversity through rotational grazing that restores soil and makes it resilient against drought, weeds, and pests without poisons.

At the Iowa Organic Conference the same week the climate assessment was issued, a farmer from Waverly said he looks to gross $150,000 on 83 acres growing heirloom corn his father developed in an organic rotation. A cattleman from southwest Iowa spoke of feeding three families off 700 acres without chemicals, and while restoring native prairie with grazing. The director of the Iowa State Extension Service noted that the average organic farm is grossing $1,000 per acre this year. The conventional corn grower working 2,000 acres will gross $600-800 per acre.

Sustainable, or regenerative, agriculture is catching on. The Practical Farmers of Iowa are preaching change to crowds of up to 1,000. Thirty years ago they were regarded as freaks and outcasts by the ag establishment.

If simple and affordable conservation practices were adopted, productivity losses could be minimized. Eventually, they will have to be. As the report notes, the soil already is being lost at alarming rates and will not be able to sustain the existing system. The corn genome was only mapped in 2009, and therein might lie some hope for advancements in a hungry world. Ultimately, Nature will demand that we heel to it. We are feeling it now—in a dying Gulf of Mexico, in declining farm income, in rising crop insurance costs subsidized by the taxpayers, and in crop storage problems—whether the president wants to believe it or not. You don’t have to look into the future to see what’s happening now, a slow-moving catastrophe in food production, security, and global stability.