Ryan Berry/Investigate Midwest

Ranchers must pay $1 per head of cattle sold to an organization some say works against their interests. The organization, known as a checkoff, says it represents producers of all sizes.

For 28 years, rancher Kyle Hemmert ran cattle auctions out of his sale barn near Oakley, Kansas. He had a front-row seat as the industry changed over the decades, and he didn’t like the direction it was going.

This article is republished from The Midwest Center for Investigative Reporting. Read the original article here.

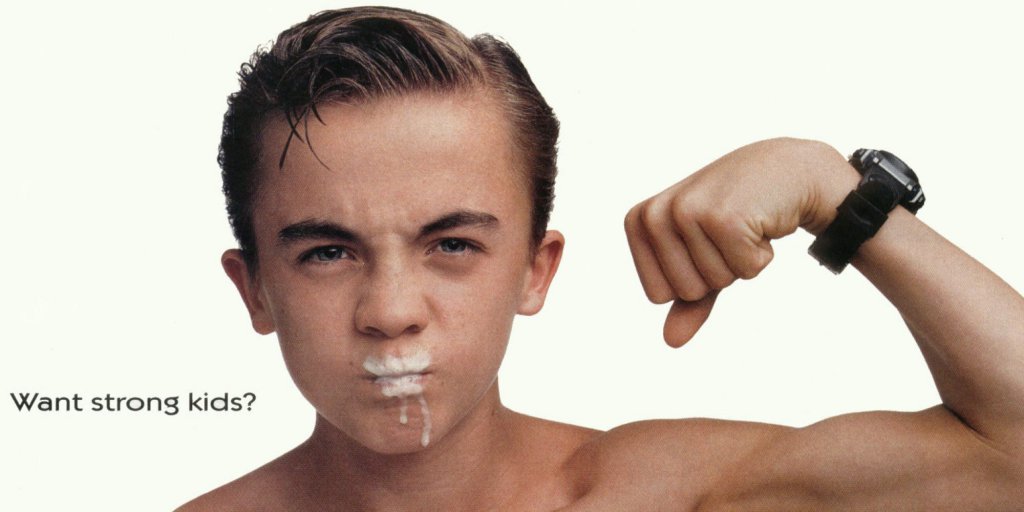

Pictured above: Bill Bullard, CEO of R-CALF, stands amongst cattle at Brad Kraft’s K4 Cattle Company on Sunday, Oct. 24, 2021, near Billings, Montana.

The number of buyers at the auctions dwindled over the years, and sometimes, only a couple placed orders. Cattle prices were dropping, and, with less competition, Hemmert found it harder to sell cattle at market price.

For each head of cattle sold, Hemmert and his staff were required to take $1 out of the seller’s payout and send it to the national beef checkoff program, which funds beef promotion and research.

He estimates that his barn channeled $1.3 million to the checkoff over the years, but he didn’t see the funds solving any of the industry’s problems.

Some ranchers, including Hemmert, say the checkoff isn’t achieving its intended purpose. Instead of benefiting producers, they argue, it’s channeling profits to a handful of powerful meat companies, who are in turn driving down cattle prices and producer revenues.

By 2020, Hemmert was burnt out, and when he had an opportunity to sell off the business, he took it. Now, he focuses on raising his own cattle.

Hemmert is vice president of Ranchers-Cattlemen Action Legal Fund United Stockgrowers of America, or R-CALF USA, an association of independent ranchers advocating for the success of cattle producers.

Rancher Kyle Hemmert. with his cattle near Oakley, Kansas on Monday, November 1, 2021.

Amanda Focke/Investigate Midwest

For years, R-CALF USA has been embroiled in lawsuits against the U.S. Department of Agriculture, which oversees the checkoff program, seeking reforms it says would tip the scales in favor of ranchers.

A judge ruled last month that the group’s latest lawsuit can proceed to the discovery stage, allowing R-CALF USA and its lawyers to gain insight into the inner workings of the checkoff administration. Ranchers have criticized the checkoff as lacking transparency.

At the core of the issue is the divide between producers — those raising and selling cattle — and the meatpacking companies purchasing and slaughtering the animals.

Ranchers fund the checkoff, but it’s the meatpackers who benefit most from the program’s promotion of generic beef, rather than U.S. beef, said Bill Bullard, CEO of R-CALF USA. Back in the ‘80s and early ‘90s, advertising generic beef still benefited small producers, he said.

“But today, given the complaints of abuse of market power in the system, and given that the marketplace is fundamentally broken with retail prices and cattle prices actually moving in opposite directions, the marketplace is dysfunctional,” Bullard said. “And the promotion of generic beef is now working against the interest of producers.”

The Cattlemen’s Beef Board, which administers the checkoff funds and hauled in more than $40 million in revenue in 2019, said the organization represents farmers of all sizes.

“From the smallest family-run farms to the largest feedlots, everyone who pays into the program gains from the Checkoff’s promotion, research, and education efforts to increase demand for beef,” said Greg Hanes, CEO of the Cattlemen’s Beef Board, in a written statement provided to Investigate Midwest.

The USDA did not provide comment by publication time.

The ‘wreck’

Vaughn Meyer remembers when the cattle market fell apart.

The 72-year-old rancher was in his 30s, helping his father run the family ranch in northwest South Dakota, when inflation and feed costs started driving up consumer prices for beef. In response, women, who controlled the purchasing decisions of most U.S. households, organized a beef boycott that Time Magazine in April 1973 called “the most successful boycott by women since Lysistrata.”

The boycott pressured then-president Richard Nixon to impose temporary price ceilings on store-bought beef in an attempt to drive down prices across the industry.

Vaughn and his father couldn’t afford to maintain their herds — they had bills to pay, and selling the cattle to slaughter wouldn’t pay the debt. So they sold nearly all of their purebred Angus to breeders, and Vaughn traded some for dairy cattle.

Meanwhile, meatpackers laid off their workforce for a lack of cattle to slaughter.

The number of cattle in the U.S. hit a historic high that year as ranchers held onto their herds, fattening them up with the assumption that prices would increase again when the price ceiling came to an end.

But the relief never came. When the price controls expired, beef flooded the market, driving prices even lower than before. Thousands of ranchers, unable to afford to keep feeding their herds, sold off their animals and never recovered.

The ranchers who survived “the wreck” wanted a solution to the industry’s woes.

Charlie Ball, executive vice president of the Texas Cattle Feeders Association, had a solution. It was a national checkoff program, which would collect a small fee on each cattle sale across the country and use the funds for beef research and promotion.

Ball’s initial proposal failed to pass a referendum of cattle producers in the ’70s. But the idea stuck, and, with a few revisions, the checkoff became law in 1988, requiring sellers to pay $1 per head of cattle sold to the Cattlemen’s Beef Promotion and Research Board.

Meyer wasn’t always an opponent of the checkoff, having voted in favor of the program in the 1988 referendum.

But as he watched the industry change and become increasingly consolidated over the decades, he lost faith in the ability of the checkoff to benefit small-scale producers like himself. He started advocating for change. He’s now the checkoff committee chair for R-CALF USA.

At the top of R-CALF USA’s list of demands for the checkoff program is a change in advertising to focus on local and American beef.

Checkoff funds are currently only used to advertise generic beef, with no distinction between U.S. beef and imported meat products.

Meatpacker revenues, aided by beef imports, are on the rise while American cattle prices have dropped. Currently, four companies control 85% of the cattle market, according to the Open Markets Institute.

Bill Bullard, CEO of R-CALF, stands amongst cattle at Brad Kraft’s K4 Cattle Company Sunday, Oct. 24, 2021, near Billings, Montana.

Ryan Berry/for Investigate Midwest

“I would like to see a reform in the checkoff,” Hemmert, the Kansas rancher, said. “But if there’s no reform, then I’d like to see it be gone. Because if you’re not going to promote my beef, I really don’t feel like I want to promote beef in general, especially if we’re importing as much as we import.”

Hemmert said he’s interested in a voluntary checkoff and more representation of small-scale ranchers on the Cattlemen’s Beef Board.

“Some states do have methods of labeling their own locally produced beef; however, as a national program, the Beef Checkoff is designed to serve everyone that pays into it — and that’s both domestic producers and beef importers,” said Hanes, the beef board’s CEO.

COOL it, some ranchers say

By law, checkoff funds cannot be used for lobbying — only for the promotion and research of beef consumption. The funds can only be distributed to contractors who are “established national, nonprofit, industry-governed organizations.” But checkoff funds can still go to organizations that lobby, as long as the lobbying is funded separately.

While checkoff funds must be kept separate from lobbying or political funds, some independent ranchers take issue with the exchange of money between the Cattlemen’s Beef Board and organizations that represent the largest agricultural companies in the country.

There are 12 organizations that receive checkoff funds in addition to qualified state beef councils. The contractors include the National Farm Bureau Federation, the National Cattlemen’s Beef Association and the North American Meat Institute, which represents meatpacking companies.

For fiscal year 2020, the North American Meat Institute received nearly $1 million in checkoff funds designated for promoting beef and veal, spokesperson Sarah Little said.

“Checkoff funding used for the promotion of beef is spent on activities like building websites, buying ads and other promotional efforts,” Little wrote in a statement to Investigate Midwest. “NAMI must compete for Checkoff funds for promotional activities and is again subject to strict oversight from the Beef Checkoff.”

In 2015, NAMI, the National Farm Bureau Federation and the National Cattlemen’s Beef Association lobbied for the repeal of mandatory country-of-origin labeling, or COOL, which had been in place since the implementation of the 2002 Farm Bill.

That year, after several years of litigation and appeals, the World Trade Organization determined that mandatory country-of-origin labeling was in violation of U.S. trade agreements with Canada and Mexico.

In his testimony to Congress over the repeal, Iowa Farm Bureau Federations president, Craig Hill, said the Farm Bureau opposed mandatory country-of-origin labeling because it feared retaliation from Canada and Mexico.

That sparked legislation in Congress to repeal mandatory country-of-origin labeling, which was replaced with a voluntary labeling program.

A Senate bill introduced in September by a bipartisan group of senators would reinstate mandatory country-of-origin labeling for beef in a manner that is compliant with the WTO’s ruling.

NAMI continues to oppose mandatory country of origin labeling, Little said.

“Some producers support mandatory country of origin labeling; others don’t. Regardless, according to the Beef Act & Order, the Beef Checkoff cannot be involved in political activism or lobbying, and legally has no role or voice in implementing — or not implementing — COOL,” Hanes said.

Proponents of the checkoff program see the benefit in checkoff-funded market research like that conducted by Kansas State University, the only university approved to receive checkoff funds.

KSU agricultural economic professor Glynn Tonsor surveys 2,000 consumers per month on their meat consumption habits and publishes the market research for public use. The project is funded in part by the beef and pork checkoff programs.

“I think that’s a project that’s checkoff funded that wouldn’t exist otherwise,” Tonsor said.

‘The whole checkoff thing needs cleaning up’

R-CALF USA is working with lawyers from Public Justice, a nonprofit legal advocacy organization, to sue the U.S. Department of Agriculture, which oversees the checkoff, in hopes of forcing changes to the program.

A previous suit brought by R-CALF USA and Public Justice forced the USDA to enter into written agreements with 15 qualified state beef councils. Now, in their current lawsuit, R-CALF USA is arguing that these agreements were made illegally, without public input.

“We need an understanding of the decision process USDA used to change the regulatory requirements of the checkoff without providing an opportunity for public comment,” Bullard said.

In September, a judge ruled that the lawsuit would proceed to discovery, in order for the court to determine whether R-CALF USA has standing in the suit. Essentially, R-CALF USA needs to prove that their members — independent ranchers — have suffered harm as a result of the USDA agreements.

The discovery process may bring information to light that could lead to more changes in the checkoff administration, said David Muraskin, litigation director of the Public Justice Food Project, who is representing R-CALF USA in the lawsuit.

George Wishon, a fifth-generation rancher and regional director for R-CALF USA, said he’s looking forward to learning more about how decisions are being made about the checkoff funds.

“The whole checkoff thing just needs cleaning up, in all honesty,” Wishon said. “I think the idea, way back when, had a lot of good merits, but it’s gone sideways in the last few years.”