Forget what you’re hearing about online shopping. There are more grocery stores than ever.

At least, that’s the word from the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA). A new study from the agency out this month shows that the number of grocery stores in America has increased by 7 percent over a decade, with much of that growth happening in cities and other populous counties.

The question, of course, is, who’s behind the growth? Big surprise: It’s not small businesspeople.

By examining a decade of data between 2005 and 2015, the researchers found that chains with four or more stores claimed 3 percent of market share that formerly belonged to independents.

So while the grocery market in general is growing, it’s also consolidating. The study doesn’t differentiate between, say, a regional chain with a dozen stores and America’s grocery oligarchy—Walmart, Kroger, Albertson’s, and Publix, with thousands of locations across the country. But one thing is clear: There are more stores, and fewer stakeholders.

The USDA study finds that independents are three times as likely as chains to meet the culinary needs of growing minority populations

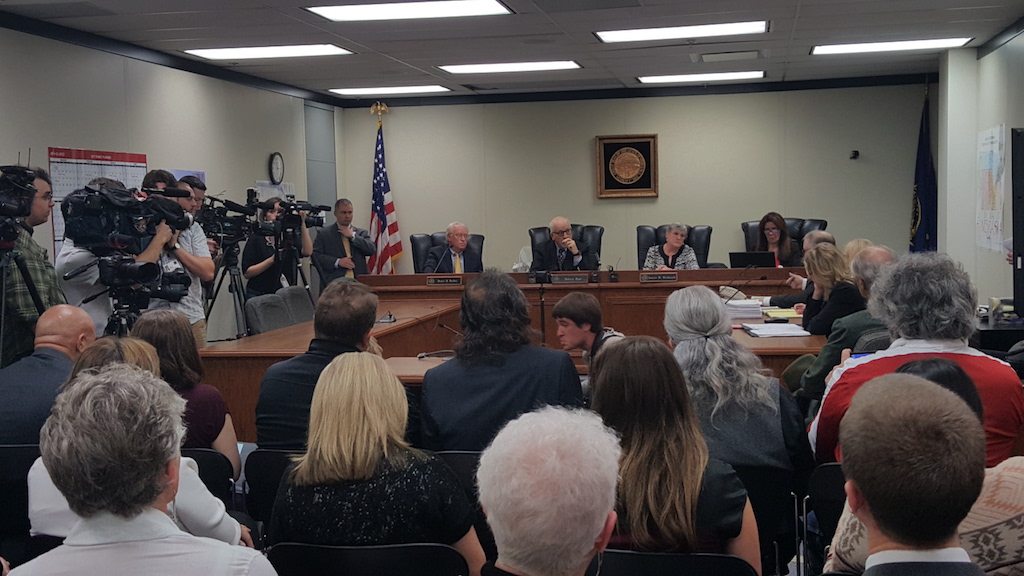

That doesn’t surprise Joseph Welsh, a long-time retail consultant who goes by “Joe the Grocer.” For the past two years, he says, independent grocery sales have gone down overall, albeit with a slight bump in October. Today, even though they make up at least half of all food retailers in 44 percent of U.S. counties, independents account for just 11 percent of total grocery sales, according to the USDA report. Compare that to the big four, who alone represent over 42 percent of sales. Their market share has increased every year since 2012, according to unpublished research by USDA economist Howard Elitzak.

Welsh says the downturn is due to increased competition from a variety of sources—whether it’s convenience stores adding milk and bread to their assortments, or direct sellers online, or corporate-owned “neighborhood markets,” like Walmart Express and Publix’s expanding line of smaller-scale GreenWise Markets.

“In the Southwest, neighborhood markets have done really well,” says Welsh, who comes from a family of independent grocers in El Paso. If they were still in the business today, he says, they’d be a target for corporations, eager to home in on the corner-store market share.

Meanwhile, independent store strongholds remain in Great Plains states and low-income and rural environments, according to USDA. That shouldn’t come as a surprise. For one—and it’s obvious—larger chains just don’t think they can turn a profit in a small town.

“It’s the old Willie Sutton line,” says Nedelman. “Why do you rob banks? That’s where the money is.”

But even there, a profit isn’t guaranteed. Welsh says independent grocers—which are primarily superettes, according to the USDA report—are now facing stiff competition from dollar stores. As convenience stores did in the city, these value-minded outlets cut into grocers’ turf, adding perishables, money services, and affordable private-label products.

Ultimately, the average independent grocer can’t provide the fresh produce that a supermarket can

Still, rural America’s rapidly changing demographics—with Hispanics representing half of the population growth—may create opportunities for independents. The USDA study finds that independents are three times as likely as chains to meet the culinary needs of growing minority populations. That may be because independents have the flexibility to respond to a community with shifting tastes. They can change the product mix, or the store concept, or even the name, without red tape. Independent stores in rural Texas, for example, often change to cater to Latinos, says Welsh.

Despite the stiff competition from deep-pocketed corporations, though, Welsh doesn’t think independents are permanently screwed in cities. One thing that keeps independents growing, at least in his experience, is when large chains, up to their eyeballs in debt, go belly-up and sell off their stores.

Look at what happened to Furr’s, a Texas grocery chain. In the late 1980s, backed by foreign capital, the Lubbock-based company completed a federally contested purchase of 59 Safeway stores and warehouses, expanding its reach into New Mexico. But within a few years, the company buckled under the weight of too much real estate, and was forced to liquidate its assets—before eventually declaring bankruptcy. Welsh says independent grocers, like his family, were the beneficiaries, and gobbled up the stores on the cheap.

Call them the leftovers.