Photo by Libby Anderson/Flickr/Nicolas Raymond/Graphic by Talia Moore

A weekly series about one chef who closed three restaurants during the pandemic—and intends to get them back.

(Editor’s note: In early March, we asked Gavin Kaysen if he would allow us to chronicle his experience from the moment he shut down his three restaurants until they re-opened. To our surprise, given how uncertain the future was, he agreed. The Counter’s West Coast editor, Karen Stabiner, has interviewed him every week since then. It wouldn’t be quite accurate to deem this the final installment in our series, but rather another chapter for restaurants, following an all-too-brief intermission, in America’s pandemic apologue. Re-opening is not the end anyone thought it would be, so we will check in again with Kaysen over the coming months.)

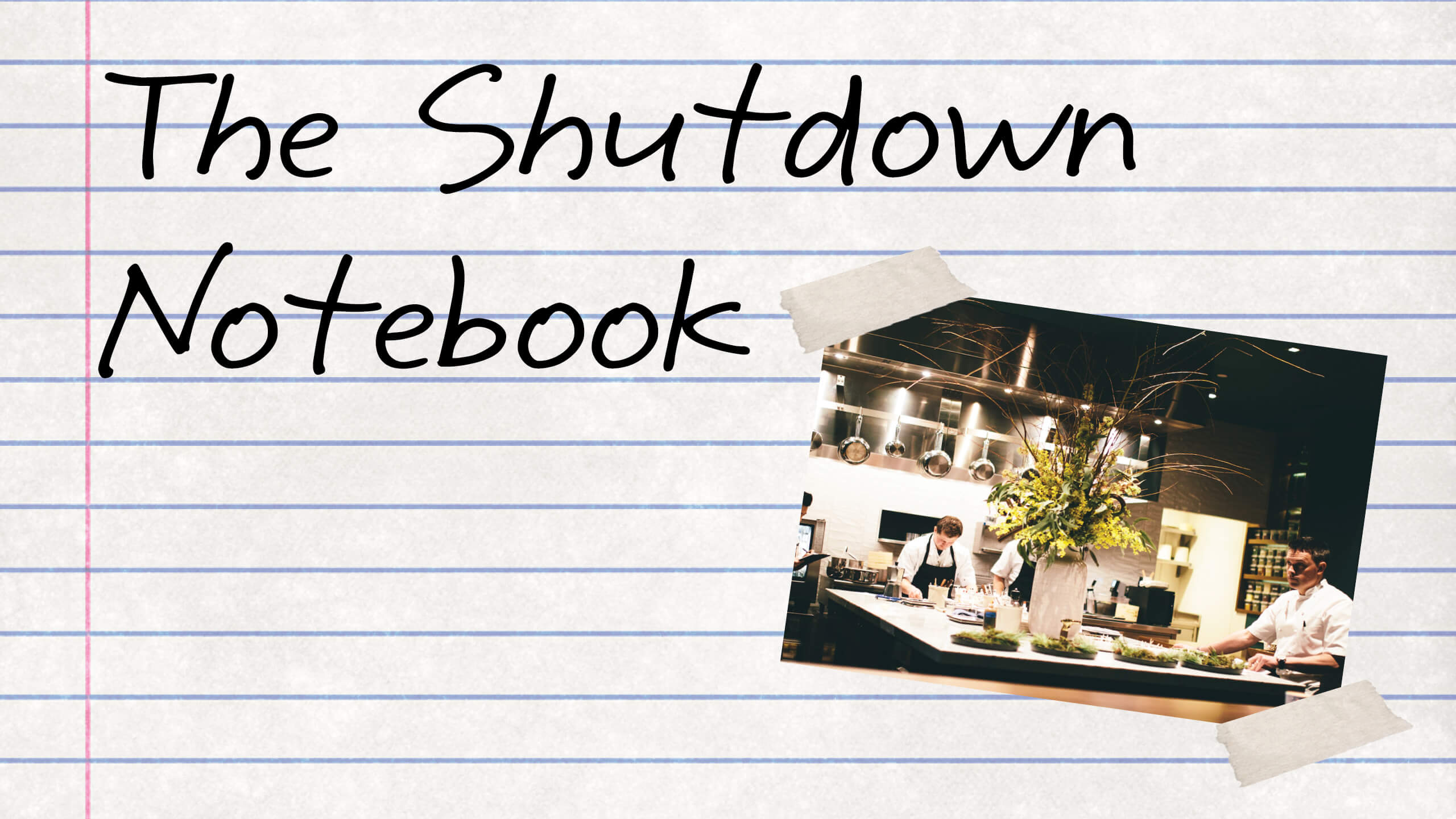

Not a bad track record, as chef/owners go: Gavin Kaysen was one of Food & Wine’s best new chefs in 2007, when he was 28, and a year later won the James Beard Rising Star Chef award. Ten years after that he won the Beard for Best Chef Midwest; his first restaurant, Spoon and Stable, was a finalist for best new restaurant in 2015, as his second, Demi, is this year. He represented the U.S.A. in the international Bocuse d’Or competition in 2007, and helped guide Team USA to second place, in 2015, and its first win, in 2017. His restaurants—Spoon and Stable, Demi, and Bellecour—have been packed since they opened. In a notoriously risky business, he is as safe as a bet gets.

That was then. This is now:

He closed the restaurants when Minneapolis shut down to keep Covid at bay, furloughed most of his staff, and went into the take-out and delivery business at Bellecour and Spoon and Stable.

He spent his downtime considering his options: plastic shields versus masks, disposable menus versus ones that could be disinfected, the labyrinth of PPP funding (which he got, returned, and reapplied for when the deadline for re-hiring was extended). He wondered how best to provide service without human contact. How to provide hospitality, a far more difficult proposition.

He didn’t always sleep well, but he managed to convey a glass-half-full attitude almost all the time. Fifty-percent indoor occupancy wasn’t enough to survive, the numbers told him that, but it was enough to get to the end of the year, closer to a vaccine. It would give him more time to figure out long-term answers, and would enable him to bring his employees and his vendors back to work, if at a reduced level.

“We are losing more than we have to gain.”

He re-opened Bellecour on June 25, followed by Demi on July 8 and Spoon and Stable on July 10. It took one week at each place to learn a harsh new lesson: People might have permission to go out to eat, but they weren’t ready; Covid and continuing protests in the wake of George Floyd’s murder, mixed with what was by now the habit of staying home, meant that even the half-inventory of seats failed to fill on weeknights.

On the morning of July 13, he contemplated just how bad it might get, and what more he might have to do to prevail. He considered a revised definition of survival, one that might not include all three restaurants, something he hadn’t thought much about before. It was important to stare it in the face, as though that would make it back off.

The next afternoon a Bellecour employee tested positive for the virus, and Kaysen shut down immediately—temporarily, he said, to deep-clean the restaurant.

A day later, he closed Bellecour permanently. It was a sadly simple decision, according to a long email he sent to everyone involved: “we are losing more than we have to gain.”

There are no safe bets in the restaurant world right now. When he got the news about his employee’s positive test, Kaysen reposted a graphic from Los Angeles chef and restaurant owner Ludo Lefebvre that read:

Many of your favorite restaurants may not reopen in

6 weeks.

Or 8 weeks.

Or 3 months.

Or ever.

—

Dave Puente/Nicolas Raymond/Flickr/Graphic by Talia Moore

Yesterday’s gone

I haven’t slept in five days. My workday starts at 6 a.m., with my lawyers, trying to figure all this out. I cried like a baby when I had to tell the team yesterday—the management team, about 15 of us overall, plus the team at Bellecour. I was not in a good place.

We had to call 80 people to tell them they lost their jobs. I put my phone on do not disturb but I saw a tweet in the two seconds I looked, a state commissioner talking about jobs coming back to Minnesota, and I wanted to write back and say, Really? But I just didn’t have the energy.

Everyone’s in trouble; it just looks different from one restaurant to another.

This is a tidal wave. It took us out in a heartbeat.

A lot of the messages we’ve been getting are, If you can’t make it, what does that mean for everyone else? But everyone’s in trouble; it just looks different from one restaurant to another.

I thought Bellecour would have a hard time bouncing back, but I never realized how hard it would be. I don’t think that the one positive test sped it up; it just forced me to understand reality. Gave me time to look at the numbers. And to see the financials—it just really fucking sucks.

We need to understand that it’s for the greater good to save restaurants, and I’m only talking restaurants because that’s my business, but there are so many other industries impacted as well. Honestly, if we’re not going to get any more government help then every restaurateur should look at their books right now, and ask, How will I get through the next six months, and what does that look like, and ditto for one year.

It is a really, really somber moment.

—

Dave Puente/Nicolas Raymond/Flickr/Graphic by Talia Moore

The realities of reduced occupancy

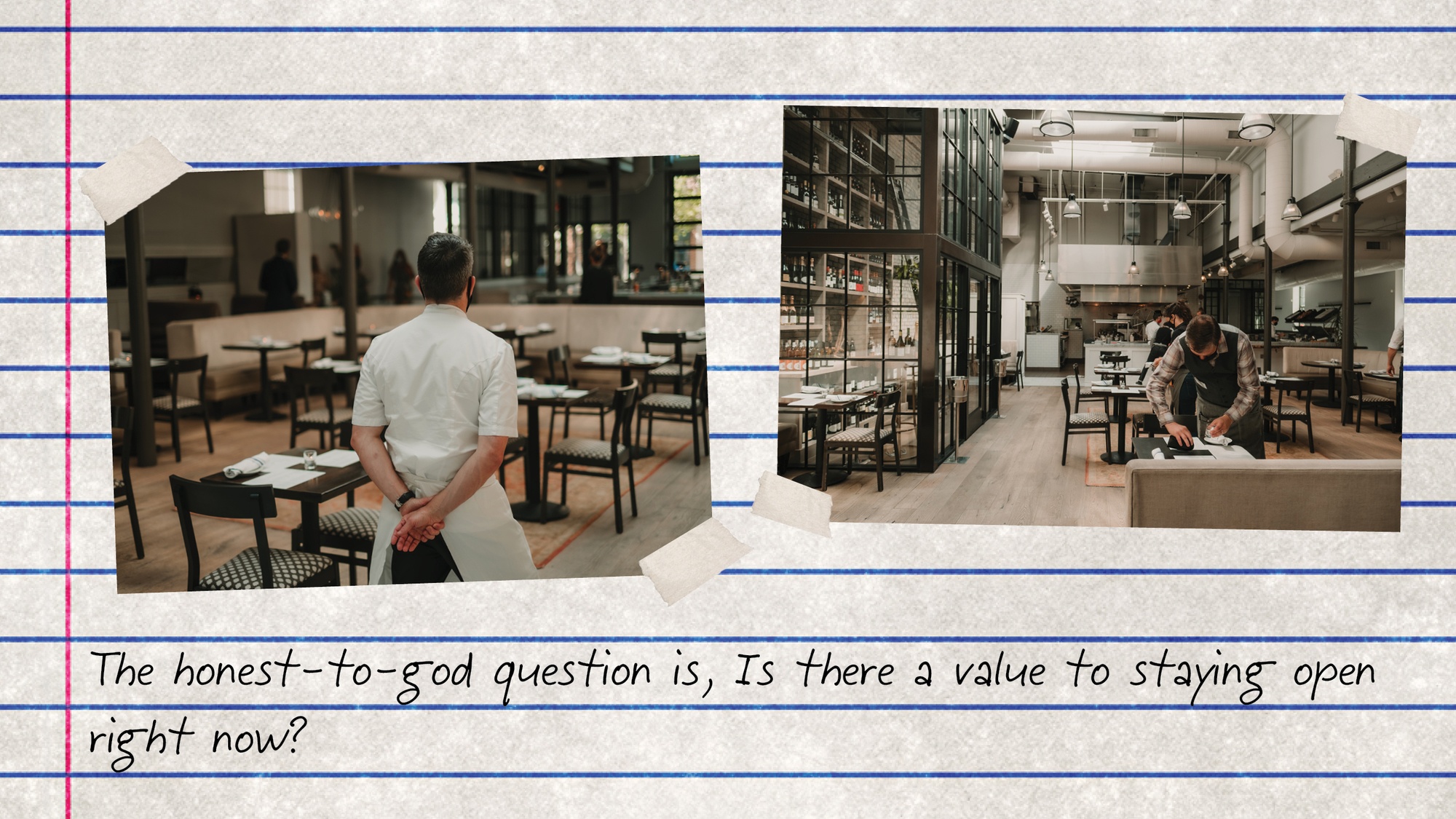

The honest-to-god question is, Is there a value to staying open right now? With everything we have to deal with on a day-to-day basis—and I don’t have data yet, but I will—I have to think about whether it’s worth it.

Take last Monday night at Spoon. We only had 40 reservations, even though at 50-percent capacity we could still feed 120 people. It’s very slow. The first Friday and Saturday were both fully occupied at 50-percent capacity. The first Sunday was not. We did about 60 percent of what we were allowed, 80-something people, and the rest of the week was what I would call slow.

In a normal summer, at 100-percent occupancy, an average Monday would be 160-170 people. Now we’re talking about 40. It’s crazy to say the least. I mean, it’s good some days, not so good other days, but it’s surely not business as normal, and even the full 50 percent is 50 percent of our revenue. If we’re lucky.

In a normal summer, at 100-percent occupancy, an average Monday would be 160-170 people. Now we’re talking about 40. It’s crazy to say the least.

And what if we get down to 75-percent less revenue than usual? Is it valuable for us to stay open, for the brand? What will it cost us to stay open? I don’t know the answer to that question. But I will.

I’m a little bit surprised by it, but I guess nothing should surprise me at this point. There are no business travelers, no company outings, no ‘Let me take out clients because we just closed on a deal,’ and I’m not sure how long restaurants can survive without that income. Minnesota is trending to be the second lowest state in the country, in terms of virus infections, which is a great thing to see—but a lot of people are feeling, That’s great, but the storm’s not over yet, how can we be sure? People are still scared of the virus, and we wrestle with the civil unrest here. I think people who have summer cabins have left for summer.

Spoon is the one that shell-shocked me, because it’s always been consistently busy. But we’re not in an environment now where people are ready to celebrate: The allowance of 50-percent occupancy does not mean that 50 percent of the people want to come out to eat. They could tell us we can go back to 100-percent occupancy; it doesn’t matter. It will continue to be a struggle until there’s a vaccine or an assurance that if you get sick you’ll get well.

I’m not a pessimist but I want to look at the facts. I want us to be thoughtful about this.

—

Dave Puente/Nicolas Raymond/Flickr/Graphic by Talia Moore

Truth or dare

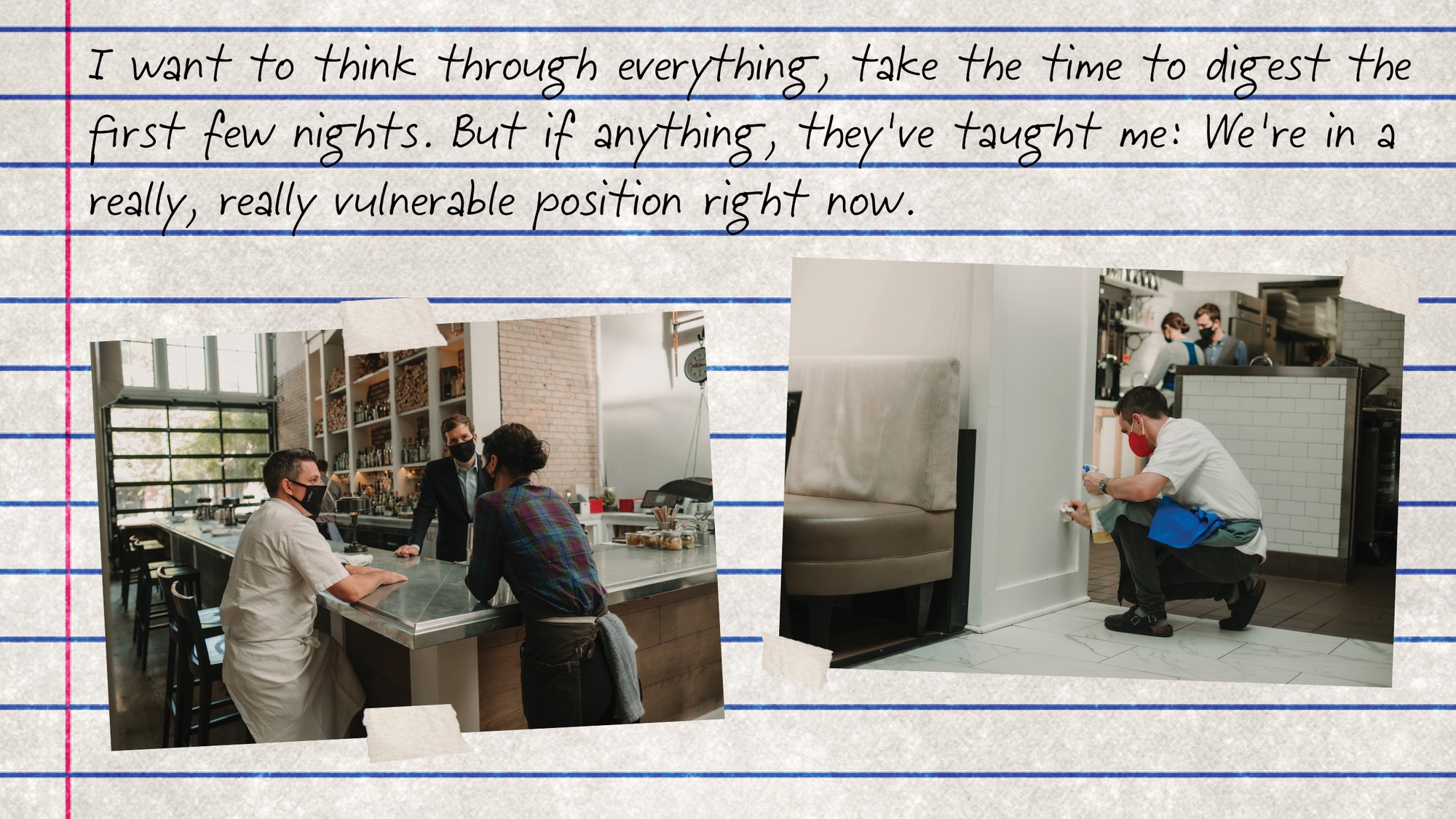

I haven’t thought through all the pros and cons of closing again. We’d have to strip everything down to make sure we had enough capital to re-open. We’d have to lay people off rather than furlough them. The expenses are too high to furlough them; we can’t afford to pay for insurance. And the question, in terms of furlough or laying off, is how long will it be? I didn’t think it’d be this long, this time.

But we didn’t need the full staff today.

If you have outdoor space you’ll tend to be more full, but Spoon doesn’t have the luxury of outdoor space; we’re confined to the indoors. We could invest money in building an outdoor space, go through the permit process, let’s say we go at impossible lightning speed and it’s done August 1, I’d still only have it for two months of good weather. And even in the summer, managing weather is incredibly difficult: There have been nights recently where we had a beautiful day and afternoon and then all of a sudden a storm rolls in for 15 minutes and wipes out the patio. You have to think about those little things.

I feel a lot less confident about getting to the end of the year.

If you do invest, what does the return on investment look like? I want to think through everything, take the time to digest the first few nights. But if anything, they’ve taught me: We’re in a really, really vulnerable position right now.

I feel a lot less confident about getting to the end of the year. If we’re only full at 50-percent occupancy on Fridays and Saturdays at Spoon, our whole business model will have to change again. This restaurant has always worked off a pretty consistent set of numbers. To see it be in flux, it’s tough to know how to navigate.

Bellecour was running at 50-percent occupancy before we closed—which are the numbers we’d put out in a winter setting, and winter months are when we lose money. It was busier than Spoon because it has outdoor space and it’s open all day, but it still wasn’t the summer-month business we count on.

I don’t know. We are in a tough spot right now.

—

Dave Puente/Nicolas Raymond/Flickr/Graphic by Talia Moore

The once and future restaurant

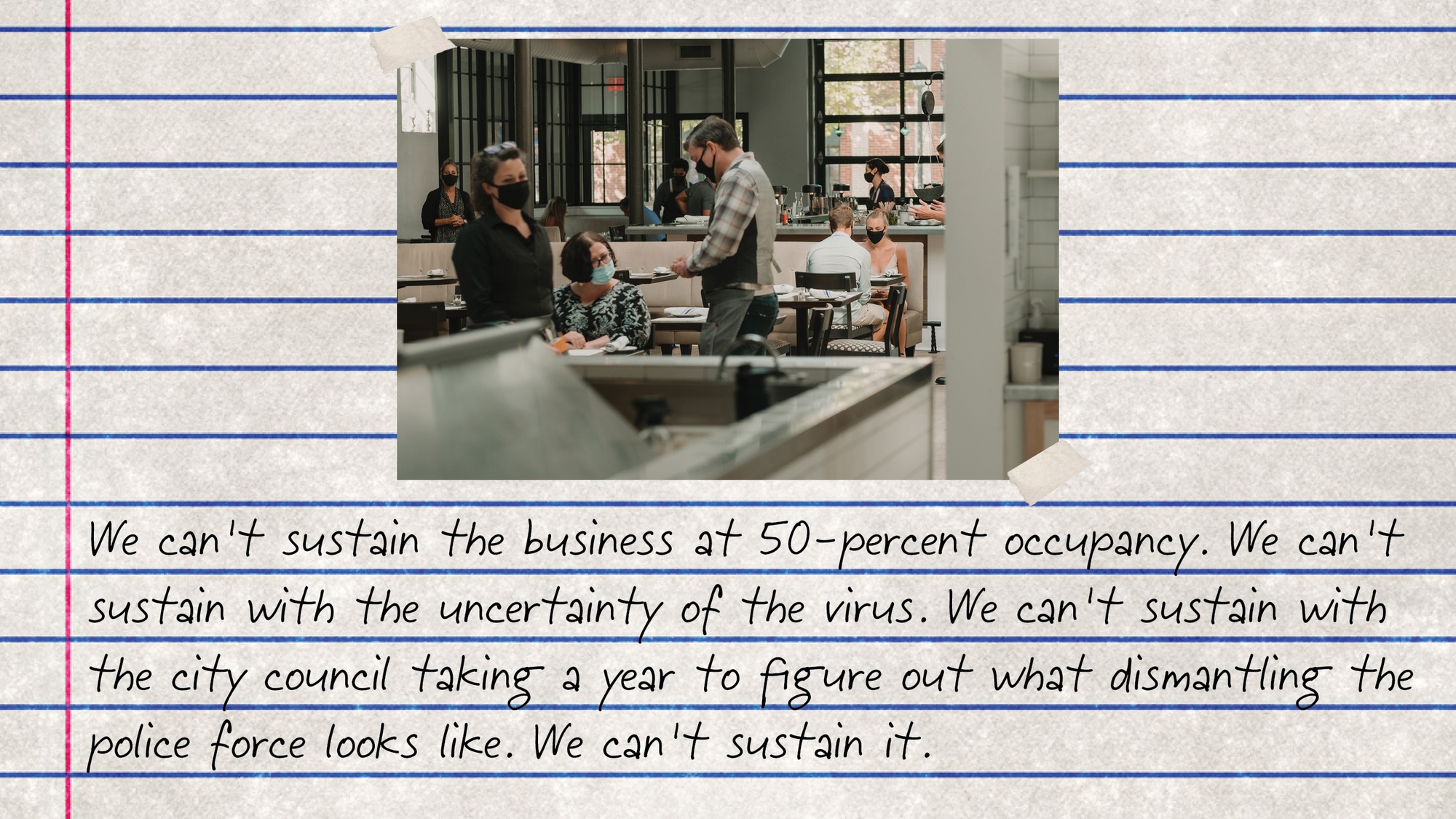

Demi’s doing great in the sense that it’s full at 50-percent occupancy almost every night. It’s a space where people feel safe. With all the guests and entire team you have maybe 17 people in the whole space, and you can see everybody. It’s a little bit of a dinner party, but you have your own six-foot section to yourself. Because of the higher average check cover, and the way the business has always run itself—it’s a ticketed event, so we understand the revenue before we walk in for the day, and can adjust based on what we have—I feel better about Demi, which gives us a bit of optimism.

It’s at capacity, and we added two tables outside for an additional four to eight people a night. Frankly, if we can do those eight, it means we’re doing only eight less people than we normally do, which is huge. That can be the difference between the success and failure of that space, but those tables go away in the winter. Or maybe not. The outside tables are underneath an awning that turns into a heated vestibule in the winter, that used to be for people who wanted privacy, or to have a cocktail and not stand at the bar. Maybe we can make that into a space, though not when it’s 30 degrees with a wind chill. But maybe it could extend our time outside a bit.

Demi feels the most stable to me. We even had first-timers who said they had had a reservation in March or April for their wedding anniversary. Once we re-opened, there they were. And a couple of guests said they were worried about coming over, but later in the meal said that it was very comfortable. I felt good. Maybe there’s just a lag time and eventually things will pick up, get to be more consistent.

I could imagine a situation where we have Demi, period. We can’t sustain the business at 50-percent occupancy. We can’t sustain with the uncertainty of the virus. We can’t sustain with the city council taking a year to figure out what dismantling the police force looks like. We can’t sustain it. I say that not as a threat but as actuality and fact. There is a future where that might happen, where we might have one restaurant, if things don’t turn around. But a more immediate possibility would be that we close down a second time, if we have to, and wait it out a little bit, see what that means.

—

Dave Puente/Nicolas Raymond/Flickr/Graphic by Talia Moore

What’s next?

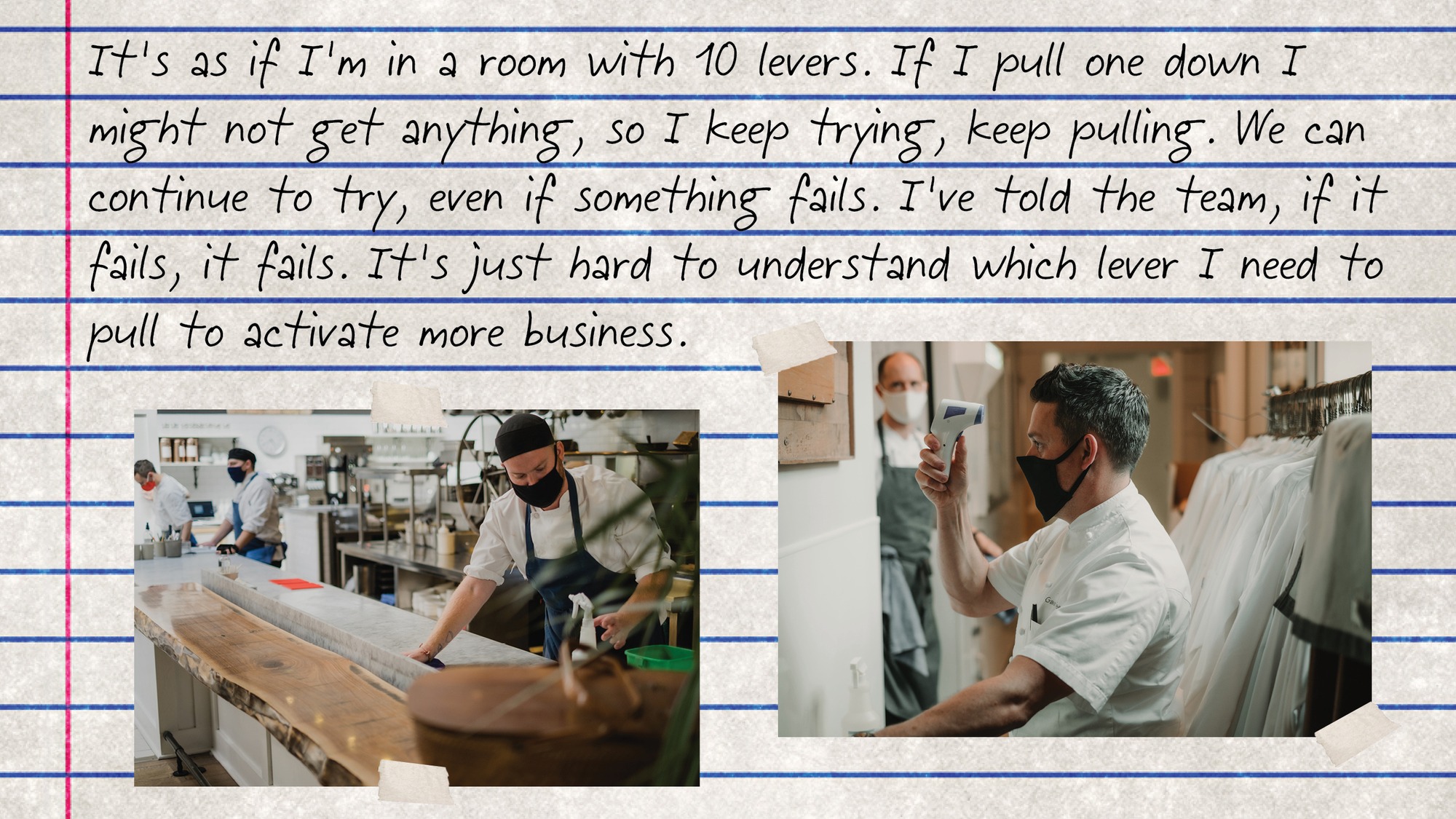

I’m trying to find a balance, understand what we can do to make it work. It’s as if I’m in a room with 10 levers. If I pull one down I might not get anything, so I keep trying, keep pulling. We can continue to try, even if something fails. I’ve told the team, if it fails, it fails. It’s just hard to understand which lever I need to pull to activate more business.

We opened a Bellecour pop-up directly across the street from Spoon, in Cooks at Crocus Hill, a retail cooking store like Sur La Table. They have cooking classes so they have a lot of space, and two coffee shops in the North Loop had shut down, so we said, ‘Well, what if?’ It feels like a big victory. A regular customer came by and said, Thank God you’re here, I can stop going to Starbucks. Those little snippets, that’s a part of restaurant humanity that’s being lost so quickly people can’t even grasp what it means to the community.

The pop-up is in some ways pulling a lever, let’s see what happens, there’s very little financial commitment to it, and on the first day it was steady and busy all morning. People were happy, neighbors are happy to have a space to go to, they’re grateful. Maybe we’ve helped create a new routine for them. Maybe we’ll create a little joy, and it’s fun to see people over there doing their thing.

People were happy, neighbors are happy to have a space to go to, they’re grateful. Maybe we’ve helped create a new routine for them. Maybe we’ll create a little joy, and it’s fun to see people over there doing their thing.

The pop-up has been a breath of fresh air. All the problems are good ones to have: We’re really busy this morning, we need a bigger van, that kind of stuff, I welcomed those calls at 7:30 in the morning. The Cooks people are happy, they said it’s so much fun, people are smiling, we’re all excited to be here. We’re just trying to figure out if we can bring a little joy to the neighborhood.

We have to figure out where to make the pastries for the pop-up, now, but we’ll figure it out. I want it to live as long as it can, and I want it to thrive. I went over at one o’clock to grab an iced coffee and a salad for lunch, and they were completely sold out of everything. They were sold out of the pastries by nine, and there’s a lot of energy and excitement.

There were two coffee places in the neighborhood that closed. Who knows. Maybe we’ll open a little Bellecour someday.

And we’re bringing take-out back to Spoon, because we got calls from regulars who said they wanted to support us but weren’t comfortable going out yet.

—

Dave Puente/Nicolas Raymond/Flickr/Graphic by Talia Moore

The waiting game

What’s frustrating for me is that Minneapolis is in a position to make some important strategic moves to help make it better as a community, and hopefully to help other communities see it as an example of how to be better. But I talked to a city council member last Friday who said he intends to spend the next year looking at data to figure out how to proceed. I said, You spend a year and I’m out of business. I can’t watch politics for a year.

Several business owners around me who own buildings are ready to sell, and others who have one year left on their lease are not going to sign another lease. Some huge shift needs to be made, but I don’t know how to effect it or help it. I have no idea what to do. I just feel that taking this much time to create a plan seems irresponsible. I’m all for whatever we need to change structurally—but can’t we find a way to make it safe for people to go out?

During the week, we used to get a ton of business traffic, people who work downtown, casual drop-ins for a snack and a drink on the way home. That’s gone. Downtown’s a ghost town.

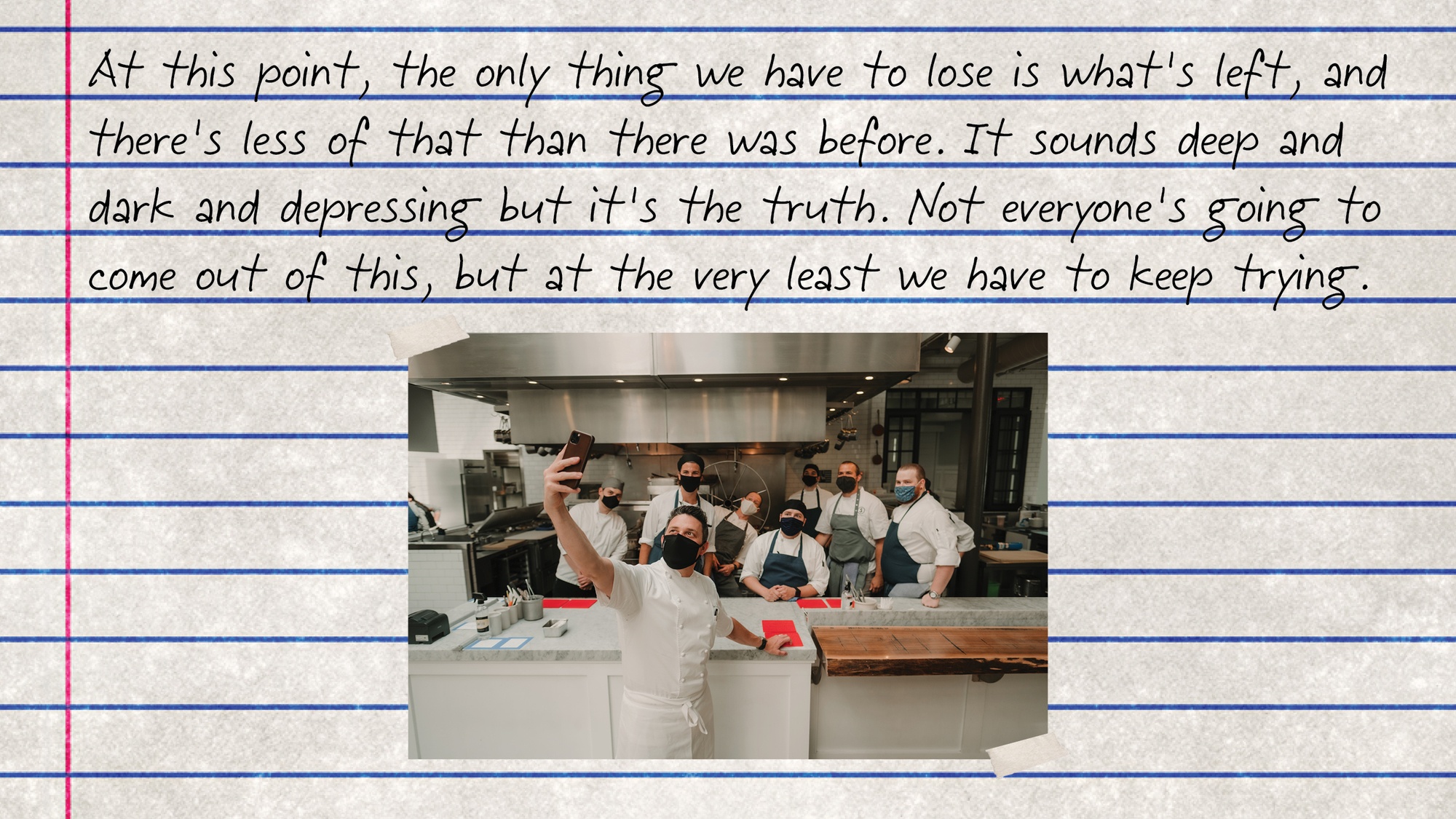

At this point, the only thing we have to lose is what’s left, and there’s less of that than there was before. It sounds deep and dark and depressing but it’s the truth. Not everyone’s going to come out of this, but at the very least we have to keep trying.

The restaurant community in general has been and will continue to be altered forever based on what happened. If I watch a movie now and there’s a scene in a restaurant or a coffee shop, all I think is, When will it be like that again? I can’t even hear what the actors are saying. When will that come back? And it’s not a financial thing, that question, it’s about the community. When does that come back? I can honestly tell you I have no idea.

It’s so important. There’s one regular, a guy who lives in the neighborhood and eats at Spoon all the time, he came in, and as a thank-you gift we gave him one of our leather-bound wine books filled with blank pages for him to write in, with a note from each of us. I went over to say hi and he was almost in tears. I was, too.

We need all to remind ourselves, educate ourselves, that food is not convenience, a restaurant is not only for convenience, it’s for restoration. You go in, you get to know the general manager, the owner, the chef, you have your regular favorite items on the menu. But you’re not there for any one of those things specifically—it’s for how that makes you feel. You want it to be a place that has a lot of soul.

At this point, the only thing we have to lose is what’s left, and there’s less of that than there was before. It sounds deep and dark and depressing but it’s the truth. Not everyone’s going to come out of this, but at the very least we have to keep trying.

Worst case scenario, we rebuild.