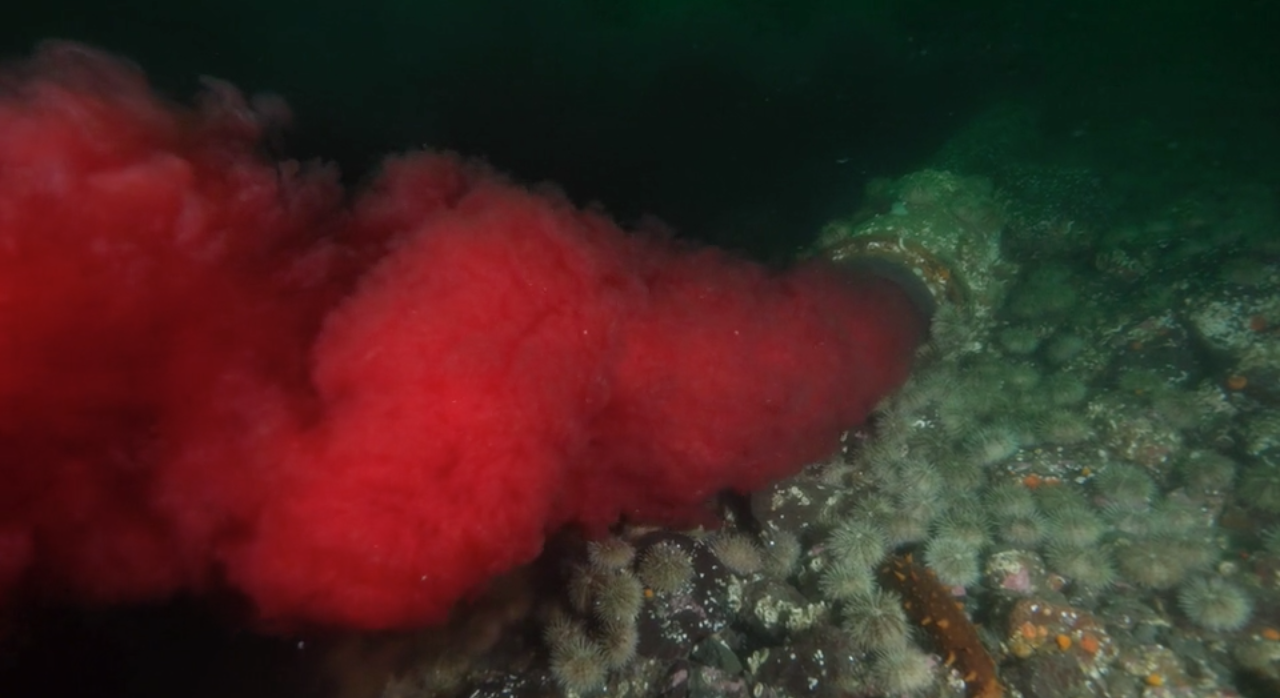

Screenshot of Tavish Campbell's video

In August, we wrote about the Great Solar Eclipse Salmon Escape of 2017, when thousands of farmed Atlantic salmon escaped their pens for the free waters of the Pacific ocean, seemingly driven mad by the moon. Since then, anti-salmon farming sentiment has been heating up along the West Coast in United States and Canada. Following the big escape, Washington governor Jay Inslee declared a moratorium on new net-pen farming operations in the state. State senator Kevin Ranker has sponsored a bill that would gradually phase out the process, ending it entirely after 2025.

The debate reached a fever pitch last week when photographer Tavish Campbell released footage of a waste pipe spewing a bright cloud of salmon blood into the ocean off the coast of British Columbia’s Vancouver Island. The “sanitized effluent” was flowing from Brown’s Bay Packing Company, a processing plant that processes over 32 million pounds of fish per year, the BBC reports. The story blew up: Buzzfeed, Quartz, the BBC, the Seattle Times, and even the Weather Network covered the graphic video.

The plant hadn’t broken any laws by releasing the waste, and representatives insisted the blood been treated to kill germs that may be harmful to wild salmon. Still, tests for common pathogens including piscine reovirus came back positive, according to BBC. The virus, which can kill up to 20 percent of infected fish in farmed salmon populations, may be contagious in wild populations as well. That’s concerning because the video also showed wild fish swimming close to the waste pipe, which is located along their normal migratory routes.

The blood-spewing pipe is a powerful visual. But there’s not a whole lot of data linking salmon pens to the spread of disease in wild populations—the industry is relatively new, and direct impacts can be difficult to prove.

Since that 2009 scare, which prompted a federal inquiry, there’s been a freeze on the construction of new salmon farms in British Columbia. That freeze is scheduled to expire in 2020.

For its part, the salmon-farming industry has made recent efforts to lessen its environmental impact, National Geographic reports. In 2013, 15 of the largest salmon companies joined the Global Salmon Initiative, a move that signaled they would limit antibiotic use and meet sustainability guidelines established by independent Aquaculture Stewardship Council.

But for some—especially those who depend on wild salmon for food and income—it’s not enough. In British Columbia, members of Canada’s First Nations and other concerned citizens have engaged in a months-long occupation of salmon farms owned by Norway-based Marine Harvest. (See Monday’s feature in Seafood News for a lengthy backgrounder on the Marine Harvest occupation, and why First Nations views the industry as a threat.) Last month, British Columbia’s Minister of Agriculture sent a letter to Marine Harvest asserting that the company should strive toward maintaining a healthy relationship with First Nations; otherwise, its fish-farming licenses may not be renewed, the Seattle Times reports.

It costs about 12 times as much to raise salmon indoors

But tensions continue to be exacerbated by the close proximity of wild populations and fish-farming pens. For now, the Namgis First Nation have advocated moving aquaculture operations to indoor tanks. According to aquaculture company Fish Information and Services, it costs about 12 times as much to raise salmon indoors, but the tanks pose no threat to wild populations. It might just be worth it.