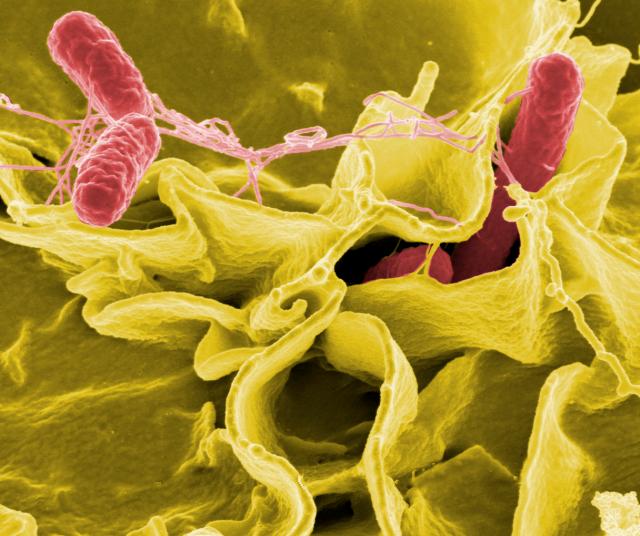

Getty Images

In 2010, the FDA recalled 550 million eggs from his plants in Iowa. Seven years later, he’ll finally be reporting to prison.

Last week, a United States District Court judge in the Northern District of Iowa made it official: Notorious egg magnate Austin “Jack” DeCoster will report to federal prison for selling the tainted eggs that led to a nationwide salmonella outbreak in August of 2010. After more than a year of legal wrangling, including an unsuccessful appeal to the Supreme Court to take up their case, both Jack DeCoster and his son Peter have been ordered to serve three-month sentences for “selling adulterated food as a responsible corporate officer.” Peter will serve first, and when he’s released from a South Dakota facility, his 83-year-old father will report to prison in New Hampshire. Each of the men pleaded guilty to a misdemeanor count and paid $100,000 in fines as a condition of their agreement. Meanwhile, the family company, Quality Egg, will pay a $6.8 million fine.

This story was a finalist for a 2018 James Beard Award Foundation in Journalism (food and health category).

Corporate executives rarely face food safety-related criminal charges as individuals (read our coverage of the first-ever corporate executive to do time for food safety violations here). But the DeCosters’ was no ordinary crime. During the 2010 episode, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) recalled a whopping 550 million eggs shipped from DeCoster-owned facilities in Iowa. The salmonella-contaminated product, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), ultimately caused a confirmed 1,939 illnesses. Based on those numbers, CDC estimated that 56,000 Americans were likely sickened.

Embed from Getty ImagesIt was a public health failure of vast proportions, tragic negligence on such an epic scale that U.S. District Court Judge Mark W. Bennett felt compelled set the tone of his dramatic, 68-page decision by opening with a passage from Marilynne Robinson’s Pulitzer Prize-winning novel Gilead. (A storm that destroys an Iowa henhouse and carries dead chickens up into the air becomes a metaphor for the bacteria that spread from Quality Egg’s disordered barns across a nation.) Even now, reading the recap in Judge Bennett’s decision, I still find myself shocked by the scene investigators found:

“…live and dead rodents (mice) and frogs found in the laying areas, feed areas, conveyer belts, and outside of the buildings; skeletal remains of a chicken on a conveyer belt; numerous holes in walls and baseboards in the feed and laying buildings; missing vent covers; rodent traps were broken, did not have bait in them, and some traps still had dead rodents in them; manure piled to the rafters in one building, which was below the laying hens; a room was so filled with manure that it pushed the screen out of the door, allowing rodents access to the building; and live and dead beetles and flies throughout the chicken barns.”

How could a company that committed violations for decades survive for so many years?

In 2010, when I was in Galt, Iowa, reporting on the recall for The Atlantic, I remember being blown away by the starkness of the details. Who would violate food safety protocols so brazenly? And how could our regulatory system allow for that level of disarray? A report issued later by the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) paints a bleak picture: Prior to 2010, USDA and the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) couldn’t even agree on which entity was responsible for inspecting egg plants and enforcing standards. USDA admits that, before the recall, the agency had “critical” information suggesting the DeCosters’ Iowa facilities had a salmonella problem. But no one could agree whose job it was to follow up. And so, nothing happened.

USDA’s Agricultural Marketing Service (AMS), meanwhile, would inspect finished pallets of shell eggs. But that amounted to a glorified sniff test: “The condition examination of shell eggs by AMS assures the eggs, at the time of certification, are acceptable, based on a visual and smell inspection,” USDA’s report said. Unfortunately, that glance-over told us little about unsanitary plant conditions, or the resultant contamination that may have lurked inside the eggs, invisible to the naked eye. USDA estimates that nearly half, and perhaps more, of the DeCosters’ recalled eggs were packed in cartons that went out with USDA’s grade mark for quality.

Rows of Jack Decoster-owned barns in Galt, Iowa

Joe Fassler

This all gets to the dirty secret of the American food system: Our regulators are overcommitted and underfunded, and inspections don’t happen the way they should. Still, even considering the lax regulatory environment, the DeCosters had to pull some strings to let things get that bad. The court found that that the company filed falsified paperwork to its distributor, U.S. Foods, which mandated an annual facility inspection and paperwork check. Then, when an AMS inspector found that shell eggs leaving the facility weren’t up to muster, DeCoster employees paid the auditor off with a $300 petty cash bribe. Moreover, the court found, employees routinely faked pack dates, selling eggs that were often days or even weeks older than they appeared.

These are flagrant violations, no doubt. Still, there’s a broader issue at play. It’s not just that a facility in Iowa sent out half a billion sketchy eggs one time, and our regulatory system missed it. Jack DeCoster is a serial corporate offender. Plants he’s owned in Iowa and Maine have been plagued with serious issues over the years, from allegations of unsafe working conditions and sexual abuse, to public health infractions and animal welfare concerns. It’s such a long, well-documented (though much of what was written about his offenses was pre-internet), and outrageous track record that, by 2010, Jack DeCoster arguably shouldn’t have been in business at all.

In a timeline for The Atlantic, I outlined the stunning number of lawsuits and violations racked up since 1949, when 16-year-old Jack DeCoster began to oversee a flock of 150 chickens on his family’s farm in Turner, Maine. It’s a long list, with criminal complaints dating back to the mid-1970s. The company was fined for doctoring log books, and, numerous times, for withholding pay from workers. There were allegations that child laborers operated hazardous equipment onsite. And out-of-control manure pits, fly infestations, and appalling smells spawned countless lawsuits. Twenty-seven residents of Turner, Maine filed a $5 million suit alleging that beetles—trucked in by the company to control fly problems—overran the town in biblical proportions. Former Maine District Attorney James Tierney, who had numerous run-ins with DeCoster during his tenure, told me a number of disturbing stories—including an incident when, after 100,000 laying hens were killed in a barn fire, company employees allegedly used a backhoe to dig a huge pit, burying the corpses in a reeking mass grave.

This all gets to the dirty secret of the American food system: Our regulators are overcommitted and underfunded, and inspections don’t happen the way they should.

In 1995, the state of Maine won a civil suit alleging that DeCoster Egg Farms kept workers in broken-down, company-owned trailer homes, without adequate water, using intimidation and physical barriers to bar employees from speaking to legal counsel. In 1996, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) levied an $80,000 fine after a man died in an explosion while welding inside a DeCoster-owned feed mill; the facility contained high volumes of dust, and the agency felt the victim was not adequately warned by his employer. That incident may have paved the way to the historic, $3.6 million fine OSHA imposed later that year for “egregious and willful violations of health and safety and wage and hour laws,” including exposed electrical wiring, exposing workers to industrial contaminants, not properly reporting workplace injuries, and refusing to offer prompt medical treatment.

The company ultimately paid $2 million, but even that wasn’t enough to improve the company culture. In 2002, DeCoster Farms settled in a suit brought by 11 female employees who alleged they were raped or otherwise coerced into having sex with their male supervisors at DeCoster-owned Wright County Egg. No criminal charges were filed, but the settlement was $1.5 million.

When I was reporting on the outbreak in Iowa back in 2010, I saw pigs carelessly thrown in dumpster outside a DeCoster hog facility

Joe Fassler

This is all just skimming the surface—my complete timeline has many more examples. But the question remains: How could a company saddled with decades of not just allegations and settlements but government citations, and record-breaking fines, and even convictions, survive for so many years?

The answer is despairingly simple. You can make a lot of money factory farming eggs. The money DeCoster’s egg businesses paid over the years—well over $10 million—just wasn’t enough to slow the rapid pace of growth. It’s almost like he could afford to factor out punitive damages as just another cost of doing business.

Until the very end, Jack and Peter DeCoster claimed they did not know about the unsanitary conditions that led to the recall. They argued that they shouldn’t be held criminally responsible, in the words of Judge Bennett, “based upon the fact that someone else subordinate to the defendant broke the law.” For the court, that just wasn’t good enough. In food and drug law, guilty intent—as Judge Bennett takes great pains to point out in his decision, citing years of legal precedent—is not necessary to bring a conviction. In other words, even if the DeCosters didn’t know what was going on under their noses, they should have.

Which brings us back to last week’s news. This is a case of two executives who faced everything over the years—lawsuits, fines, horrible press. Everything, that is, except jail time. And that’s important. When it comes to high-level corporate crimes, the prospect of serving time may be the best deterrent our society can exercise. Financial penalities, workplace violations, outraged news coverage can just be absorbed. But not so much the shame and public disgrace of conviction, the life disruption of a stint behind bars, the horror and monotony of losing one’s personal freedoms, temporarily or not.

When the regulatory system fails the public, and when companies make too much money to be threatened financially, the personal, legal culpability of executives is all we can count on. Let’s hope these two three-month prison sentences will be enough to convince the company to clean up its act, finally bringing the DeCosters’ long legal saga to a close.