Graphic by Alex Hinton | Source Images: ProVectors/Kateryna Novokhatnia/RobinOlimb/PhonlamaiPhoto/gilaxia/iStock

Impossible Foods’ plant-based ground pork substitute is vegetarian and would likely have been permitted in both Jewish and Muslim dietary traditions. But its newness and marketing as “pork” is giving religious communities pause.

There’s a classic joke in Judaism that for every Jew there are two opinions. Meant to signify a general lack of agreement about the application of religious laws (as well as our love of argumentation), the joke is based in truth—namely that in Judaism there is no clear answer to many of the tradition’s recurring questions. The same is true in Islam, where scholars have spent centuries negotiating the application of religious principles in modernity.

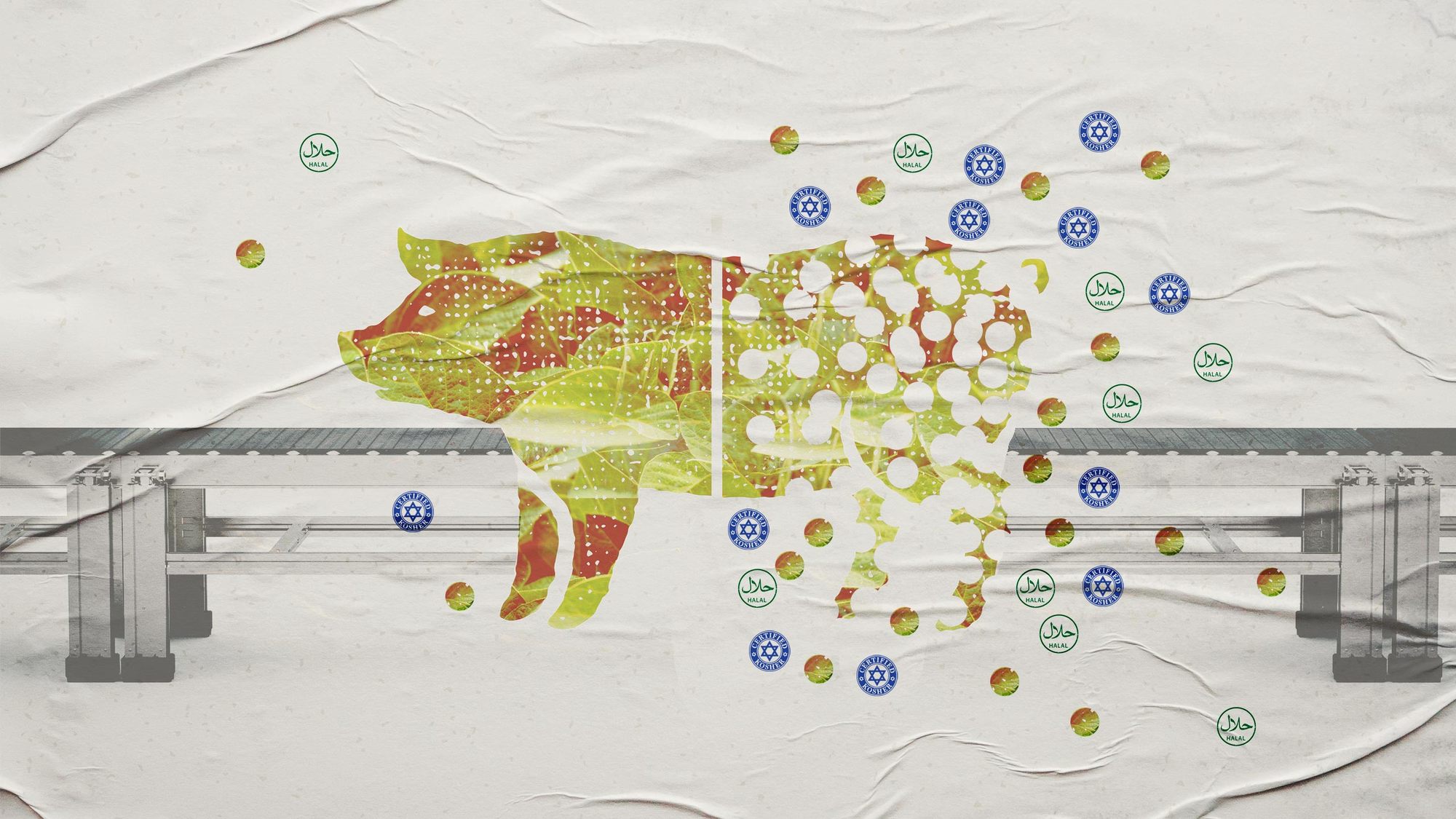

Nowhere is this lack of agreement felt more clearly than in ongoing debates about religious dietary restrictions. The growth of alternative proteins from companies like Impossible Foods and Beyond Meat, new research into genetically modified meat products, and increased attention to the ethical implications of industrial farming have forced scholars of kashrut and halal to reevaluate their interpretations of religious dietary restrictions. Caught up in a web of certifying organizations and economically-motivated food-tech companies, some religious Jews and Muslims have found that their consumption practices are increasingly divorced from the religious laws and social contexts that formed the basis of Jewish and Muslim foodways.

Both the Jewish Orthodox Union (OU), which administers the popular OU hechsher (stamp of approval), and the Islamic Food and Nutrition Council of America (IFANCA), rejected the product—not because the products were made of prohibited meat, they said, but because it resembled pork.

This conflict came to a head most recently in October, when the largest kosher and halal certifying agencies declined to certify Impossible Pork, Impossible Foods’s plant-based ground pork substitute. The alternative protein company soft-launched its Impossible Pork product in early 2020, but waited more than a year to bring it to the consumer market. While Impossible’s other products are available in supermarkets, its pork product is so far limited to a few restaurants spread across the country. In fact, it was the newness of the product that led some certifiers to approach the product cautiously.

On an ingredient level, the product would likely have been permitted in both dietary traditions—it is vegetarian by definition and doesn’t contain animal by-products. Both Jewish and Muslim dietary systems restrict consumption of pork, as well as require that permissible meat be slaughtered in accordance with religious commandments. Despite this, both the Jewish Orthodox Union (OU), which administers the popular OU hechsher (stamp of approval), and the Islamic Food and Nutrition Council of America (IFANCA), rejected the product—not because the products were made of prohibited meat, they said, but because it resembled pork. If Impossible Foods distinguished between its pork and beef products even though they are made from similar ingredients, why shouldn’t the OU and IFANCA view them as two separate and distinct products, which they’d approve or reject accordingly? Indeed, Impossible’s burger and sausage products had both received certification from the agencies.

In deciding to reject a meatless product on the grounds that it resembled a restricted meat, the certifiers waded into an ongoing argument about the larger goals of religious dietary restrictions. Historically, kashrut and halal played an important role in ensuring communal continuity by separating adherents from the broader population. “Food becomes a very tangible, visceral way of expressing religious identity,” said Febe Armanios, a professor of history at Middlebury College who co-published a recent book on the history of halal with her husband, Boğaç Ergene.

Impossible Pork Char Siu Buns are sampled during an Impossible Foods press event on January 6, 2020.

David Becker/Getty Images

Early scholarship around halal and kashrut viewed dietary practices as a way to control what enters our bodies and to promote awareness of a food’s origins, rather than as a means of exclusion. “Halal has two purposes: health reasons and as a test from God. Our job is to obey God’s commandments and not eat from the forbidden tree,” said Muhammad Musri, a senior imam at the Islamic Society of Central Florida. Rabbi Daniel Nevins, a leader in the Jewish Conservative movement and a former member of its Committee on Jewish Law and Standards, has a similar explanation: “It’s like a daily training session,” he said. “By giving us control over small decisions of what to eat, the hope is that it will strengthen us in other ways to be humble, and appreciative to our tradition and our contemporaries.”

The purposes of kashrut and halal may be similar, but the two systems are not interchangeable. While both agencies rejected Impossible Pork, their reasons for doing so were markedly different. IFANCA’s rejection was based on the name of the product alone. Using the word “pork” makes the product haram, or forbidden, regardless of its contents, said IFANCA president Muhammad Chaudry. Across the board, imams tended to side with IFANCA, viewing Impossible Pork as haram on name alone. “I’m not interested in products that replicate pork,” said Imam Musri.

The OU’s decision, on the other hand, was not a blanket rejection so much as a postponement of a final decision. “It was really a marketing issue, in the sense of people’s sensibilities,” said Rabbi Menachem Genack, CEO of the Orthodox Union’s kosher division. In other words, approving the product would have undermined the OU’s credibility as a brand. Genack added that Jewish law was a minor factor in this decision, as the primary impetus was a lack of consumer comfort with the product. He drew conclusions based on feedback from congregants and the fact that the product is still relatively new to the market.

Across the board, imams tended to side with IFANCA, viewing Impossible Pork as haram on name alone. The OU’s decision, on the other hand, was not a blanket rejection so much as a postponement of a final decision.

This is not an uncommon occurrence in the world of kosher certification. Last year in Israel, the country’s Chief Rabbinate ordered a kosher restaurant to change the name of its lamb-based bacon to “Facon” to avoid confusing consumers. And several years ago, the OU forced a kosher restaurant in the Soho neighborhood of New York City to change its name from Jezebel on the grounds that the biblical connotations of the name were too much for consumers to stomach.

To some degree, this contrast in approach is based on differing attitudes toward the pig itself. Within the food industry, kashrut and halal are often grouped together under the umbrella of dietary restrictions, despite the fact that the two operate on distinct logical frameworks. When it comes to pig, Judaism’s prohibitions on consuming the animal are far less comprehensive than in Islam. “The pig for Jews is symbolically and historically the major prohibited animal, but the prohibitions in Jewish law aren’t actually that strict,” said Joe Regenstein, head of the Cornell Kosher and Halal Food Initiative and a professor emeritus of food science. “The Koran, on the other hand, does separate out the pig as uniquely prohibited, so for them, it is a stronger prohibition.”

While Jewish law prohibits consuming the flesh of the pig, Islam prohibits consumption of the animal itself. This has led to a strange situation where, in some cases, consumption of pig byproducts (or products resembling pig meat) could be deemed kosher. Regenstein noted that JELL-O, for instance, has received a hechsher from a certifying organization despite containing gelatine sourced from pigs, something a Muslim certification agency would likely never abide.

Impossible Pork has caused something of a reckoning regarding the purpose of certifying organizations and the logic underpinning their decisions. While there is widespread consensus among religious Jews and Muslims that pork feels wrong to consume, some, like Rabbi Justin Held, a director of education at a camp for young Jews, saw the OU’s decision not to certify a meat-free alternative as the organization taking an overly zealous approach to a cultural issue that fell beyond its purview.

Impossible Pork has caused something of a reckoning regarding the purpose of certifying organizations and the logic underpinning their decisions.

“I don’t think that Moses ever heard anything about Impossible meat,” said Held. Held, who said he feels comfortable eating Impossible Pork, is enthusiastic about the product’s role in expanding the range of meat alternatives and feels that the OU overstepped its bounds by denying a hechsher solely “because it sounds gross.”

Kosher certifying organizations also face a unique situation in that their target demographic isn’t necessarily the community of religious Jews. According to Timothy Lytton, a law professor at Georgia State University and author of Kosher: Private Regulation in the Age of Industrial Food, religious Jews comprise just 8 percent of the 12 million consumers buying kosher food every year. The vast majority are individuals with other dietary restrictions who trust a hechsher as a certificate of purity.

For example, someone with a severe dairy allergy may not trust a brand’s decision to call itself “dairy-free.” But that same consumer may trust the OU’s decision to certify the product as pareve—meaning that it was not produced with meat or dairy—on the basis that those religious restrictions are more stringent.

“I don’t want to suggest that any certifying agency is going to sacrifice their religious principles for marketing,” said Lytton. “But they’re also not going to stick to their religious principles without thinking at all about the marketing implications of them. For example, the OU is not going to certify something that they feel is a clear violation of halacha [Jewish law]. On the other hand, they may not want to create stringencies that they feel are going to unnecessarily restrict the market.”

A similar debate has emerged in the nascent field of so-called lab-grown meat, or meat made from cell cultures. While these products are still early in their development, they have raised questions in both Jewish and Muslim communities about whether they should be permitted and how they should be categorized.

To some religious leaders, it seems that food-tech companies have pushed forward with meat-like products, muddying the waters around religious dietary restrictions, without adequately engaging with the communities they claim to want to attract.

Angela Weiss/AFP via Getty Images

When the first cell-cultured burger was unveiled in 2013, Islamic and Jewish leaders tentatively supported the product. Abdul Qahir Qamar of the International Islamic Fiqh Academy in Saudi Arabia told Gulf News at the time that the product would be permissible, but questioned whether it would be considered meat. Jewish organizations were similarly unsure, with the OU initially classifying it as pareve. In an interview for this story, Genack of the OU reversed that position, saying that the organization would classify cell-cultured meat products as meat. “The OU’s position is that we’re going to consider it meat,” said Genack.

To some religious leaders, it seems that food-tech companies have pushed forward with meat-like products, muddying the waters around religious dietary restrictions, without adequately engaging with the communities they claim to want to attract. “When companies become successful, they become arrogant,” said Chaudry, the head of IFANCA.

When Impossible CEO Pat Brown was asked in 2019 about pushback from religious communities over Impossible Pork, he struggled to understand the gist of religious prohibitions. “It’s a product made entirely from plants,” he told CNET. “It would surprise me if that raised any issues just [by] being called pork.”

While some Jewish religious leaders find the notion of consuming pork to be discomfiting, few found the product itself as objectionable as the logic behind it. “If you are inclined to practice kashrut, you’re supposed to just practice for the sake of the elevated level of consciousness and holiness that brings to you,” Rabbi Alan Cook of Champaign, Illinois said. In other words, workarounds to prohibitions may not be explicitly prohibited but they do go against the core purpose of kashrut.

Both Judaism and Islam are rooted in a long history of textual interpretation and disagreement, particularly concerning the way that tradition should intersect with modernity. However, many religious leaders find that tech companies ignore these issues, seeing long-standing traditions as rules to be skirted rather than complex laws that hold a positive value for religiously observant followers.

“If the job of [religious] lawmakers is to create continuities between old and new tech, many modern tech firms, with their ‘move fast and break things’ culture, often seem hellbent on tearing them apart,” wrote David Zvi Kalman, director of new media at the Hartman Institute, in an op-ed about Impossible Pork.

Still, the discourse surrounding fake meat products reflects the core purpose of religious practices like halal and kashrut: to find a path to modernity through debate and discussion.

The rapid development of these technologies has resulted in a lack of consensus within religious communities regarding the place of alternative protein products, Kalman said. He fears that this disagreement could result in additional rifts within the Jewish community, with some households deeming these products acceptable and others finding them to be unkosher. While certifying organizations like the OU will play a role in these intercommunal negotiations, many of the decisions will be made on an individual basis.

Most observant Muslims have decided against eating the alternative protein, citing Islam’s firm ban on pork. “Anything that sounds like pork, looks like pork, or tastes like pork we avoid,” said Bassem Chaaban, who leads an Isamic community organization in Florida. However, some younger Muslims said they’re willing to try it. “I don’t have a problem with veggie sausages, so I wouldn’t see a huge issue with it,” said Raheela Shah, a career advisor in London. “I mean, we need to consume less meat anyway.”

Several religious Jews noted that existing fake bacon products already have a hechsher, making debate about Impossible Pork irrelevant to them. “I wouldn’t get upset if someone served it to me, but I wouldn’t go out of my way to find it,” said Ed Bromberg, a retired research scientist from Dr. Phillips, Florida. Emily Birnbaum, a doctoral student at the Graduate Center at the City University of New York, said she has no issue with eating Impossible Pork since she has already been eating fake sausage products. “I didn’t particularly like the sausage, but that’s because it was spicy,” she added.

Still, the discourse surrounding fake meat products reflects the core purpose of religious practices like halal and kashrut: to find a path to modernity through debate and discussion. “These are rules made on the go. It’s the nature of Islamic law throughout history—they’re based on constant negotiations between people,” said Ergene, the co-author of Halal Food: A History and a professor of history at the University of Vermont. Kalman said the same is true of Judaism. “Kashrut is one of the most sophisticated ways that Jews have engaged with technology in the 21st century and 20th century,” he said.

The best way to understand how these negotiations play out in the modern world is to look at large catering events, according to Regenstein, the Cornell professor. He pointed to the process of normalizing margarine as an example of how a religious community could navigate the introduction of a new food. When the butter alternative first appeared on the market in the early 1900s, it would be served at kosher events with its wrapper visible. That way, religious Jews knew that margarine wasn’t actually dairy and could be eaten with meat. Over the intervening century, though, the wrapper was slowly removed from under the margarine, as diners began to accept that meat dinners would only ever come with a yellow block of oil, salt, and water.

“You could have a kosher kitchen of the future with one set of dishes in which you cook both meat and dairy and you serve them together. And it’s all fine from a kashrut perspective, because it’s not from living animals. But you’ll have lost something distinctive about the Jewish kitchen.”

Regenstein believes a similar trend is likely to occur with Impossible Pork and cell-cultured meat. “It’s controversial for a period of time,” he said. “Then it becomes normative.” While that normalization may be a natural occurrence, some faith leaders are concerned about how it will affect the broader purpose behind these practices. “There’s a little piece of me that does worry about the loss of distinctive Jewish foodways,” said Nevins, the Jewish Conservative movement leader. “You could have a kosher kitchen of the future with one set of dishes in which you cook both meat and dairy and you serve them together. And it’s all fine from a kashrut perspective, because it’s not from living animals. But you’ll have lost something distinctive about the Jewish kitchen.”

These foodways are also being chipped away at on a policy level. The EU’s highest court ruled in late 2020 that member states could instate bans on ritual slaughter, paving the way for country-level laws in Belgium and Greece last year. These laws mandate that animals be stunned before they are killed on the grounds that traditional ritual slaughter, which involves cutting the throat of the animal in one stroke, causes it undue suffering. Jewish and Muslim organizations say pre-slaughter stunning may end up killing or seriously maiming the animal before it is slaughtered, something that would make it both unkosher and haram.

The consensus among scientists studying religious foodways is that ritual slaughter is both fast and humane. At best, Regenstein said, these laws are visceral reactions to the bloodiness of ritual slaughter. At worst, they’re motivated by anti-semitism and Islamophobia. “It’s what makes Jews and Muslims different … and I think in Europe that does play badly,” Regenstein said.

Like alternative protein products, laws banning ritual slaughter are made by those outside the community, often without consulting religious communities. “It never even occurred to me,” Brown, Impossible’s CEO, said when asked in 2019 about pushback to Impossible Pork from Jewish and Muslim leaders. (Impossible declined The Counter’s request to interview Brown for this piece.) Similarly, there was little effort among European countries that enacted ritual slaughter bans to engage with religious leaders. Regenstein was part of a group of academics that submitted a paper to the European Court of Justice in defense of non-stun ritual slaughter—he was never contacted to discuss his findings and says the court’s final ruling showed no indication that it was read by policy makers.

In 2008, an immigration raid at one of the largest kosher meat processors in the U.S. revealed a history of unethical and illegal labor practices, including forced overtime and the use of child labor. These raids and poor working conditions are commonplace in the food industry writ large, but many Jewish consumers had believed that, by buying kosher, they were opting for an ethically produced product. In the wake of the raid and the processor’s bankruptcy, many liberal Jews began to move away from industrially-produced kosher meat, which they viewed as incompatible with the original intent of kashrut.

In line with a broader wave of skepticism toward alternative protein products, proponents of eco kashrut and green halal argue that these substitutes may further degrade traditional religious foodways.

Instead of prioritizing institutional certification, some observant Jews began to focus more on conscious consumption. In the intervening years, ethically-focused certifications like Magen Tzedek gained popularity and the eco-kashrut movement was born. A smaller, parallel movement in Islam—green halal—has also grown in recent years. Both movements encourage consumers to look for locally-produced meat processed under ethical conditions, whether or not it was slaughtered according to religious requirements.

In line with a broader wave of skepticism toward alternative protein products, proponents of eco kashrut and green halal argue that these substitutes may further degrade traditional religious foodways. Alternative proteins like Impossible Pork are highly industrialized products that require significant resources to produce. “Take Impossible Pork and compare it to a homemade falafel, which has [historical] authenticity and isn’t processed,” said Armanios, who co-authored Halal Food with Ergene. In other words, the former is a risky bet, religiously speaking, while the latter’s safety is proven by centuries of consumption. It also brings with it a historical connection to traditional observance and Islamic culture.

These newer approaches offer an alternative to the existing frameworks of halal and kashrut, but also risk further dividing the community. However, it’s these divisions that have historically pushed Islam and Judaism forward. After all, Lytton said, “one person’s workaround is another person’s disciplined halachic decision.”