Investigate Midwest

The reports Agri Stats produces and shares with meat processing companies are so detailed they can be used to fix prices, according to numerous lawsuits.

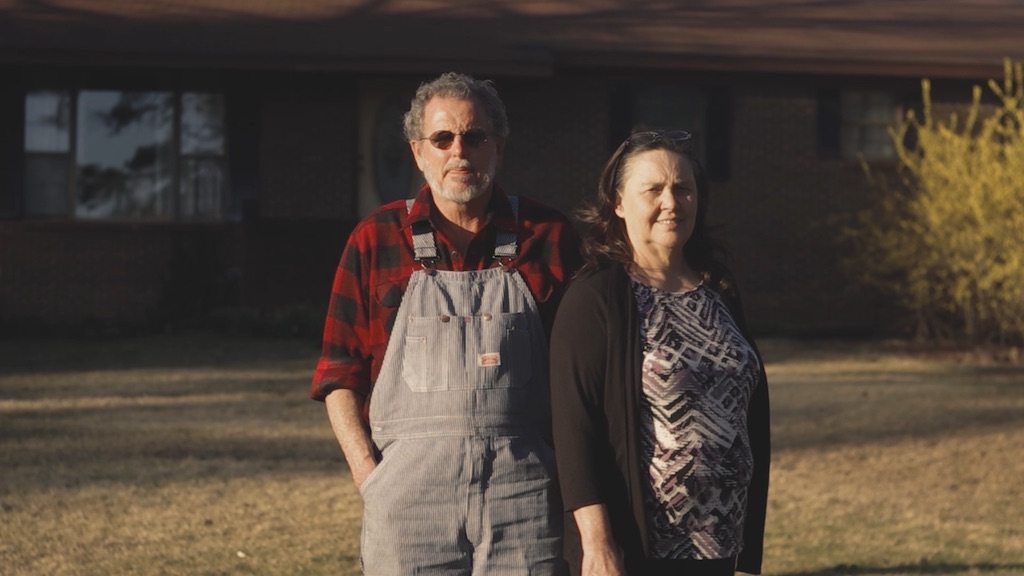

In the mid-2000s, a poultry researcher approached James MacDonald, then a branch chief for the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Economic Research Service, with some data. Its detail and depth shocked him.

This article is republished from The Midwest Center for Investigative Reporting. Read the original article here.

“My reaction was, ‘Jeez, is this legal?’” MacDonald said.

The question remains unanswered, albeit not for lack of trying: Agri Stats—a widely utilized, privately-held data and analytics firm for the meat processing industry—has been named in more than 90 lawsuits since 2016, making it the second-most sued company in the industry over that time span (Tyson Foods is first). All the lawsuits accuse the company of facilitating anti-competitive behavior because, with the almost real-time data, meat processors can see what their counterparts are planning.

Peter Carstensen, a professor emeritus at the University of Wisconsin and award-winning author on antitrust law, was also wary of the data Agri Stats compiled when he saw it.

“It looked like a serious problem,” he said. “And then the lawsuits began to come.”

“Agri Stats acted as an agent and/or co-conspirator of Defendants by facilitating the exchange of confidential, proprietary, and competitively sensitive data among Defendants and their co-conspirators.”

Most allegations are similar, even across industries. Meat producers “conspired and combined to fix, raise, maintain, and stabilize the price of” product, reads the first lawsuit, filed in 2016 on behalf of Maplevale Farms, a New York food service company.

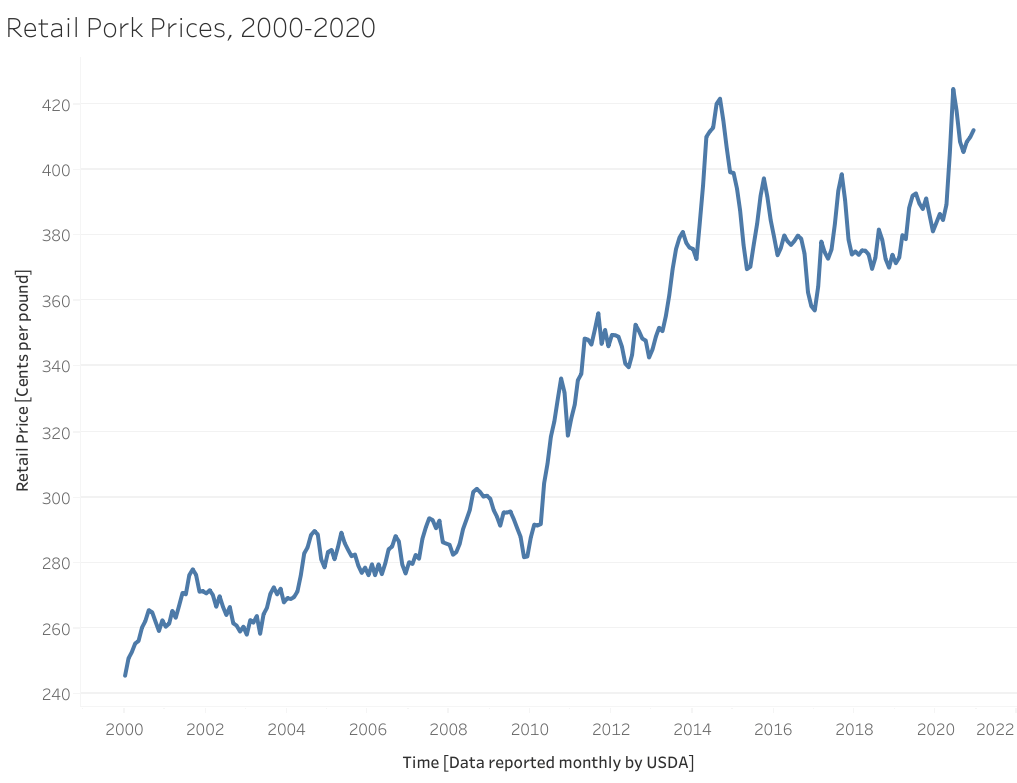

Wholesale and retail price data from the USDA reflects a rise and stabilization in consumer prices since early 2008, when the conspiracy is alleged to have started affecting the market, particularly in pork.

After remaining relatively stable between 2000 and 2008, pork retail prices shot up almost 50% from January 2008 to a then-record high in September 2014. After that peak, retail prices remained high, always at least 25% higher than 2008 levels.

Link to interactive chart here.

Investigate Midwest

The numerous complaints allege Agri Stats, which saw its earnings nearly triple over about the scope of years highlighted in lawsuits, is part of the set-up.

“Agri Stats acted as an agent and/or co-conspirator of Defendants by facilitating the exchange of confidential, proprietary, and competitively sensitive data among Defendants and their co-conspirators,” according to Maplevale’s filing.

Agri Stats did not return multiple requests for comment that included detailed questions about its operations and function.

The litigators could form a well-rounded food court: Buffalo Wild Wings, Chick-fil-A, Hooters, Sonic and Whataburger. Target, Walmart, Sysco and U.S. Foods have also sued. Geographically, the lawsuits span the United States—the state of Alaska and commonwealth of Puerto Rico are among filers.

Most of the lawsuits have been folded into industry-specific complaints for poultry, pork and turkey. Some have been settled.

Pilgrim’s Pride pled guilty to price-fixing and faces a $107 million fine as the result of an ongoing U.S. Department of Justice investigation into chicken industry price-fixing.

Tyson Foods, one of the largest meat processing companies operating in the U.S., will pay over $220 million to avoid liability in poultry price-fixing cases. In the turkey industry, Tyson has also agreed to smaller monetary settlements that include cooperation with providing documents, data and record of communication between the other defendants, which include Agri Stats.

Though a monetary amount was not noted in a federal court filing, Perdue has settled—pending judicial approval—a different class action poultry price-fixing case that doesn’t name Agri Stats as a defendant. And in pork, JBS reached a $20 million settlement while denying allegations.

Pilgrim’s Pride pled guilty to price-fixing and faces a $107 million fine as the result of an ongoing U.S. Department of Justice investigation into chicken industry price-fixing. Four of the company’s executives, plus Koch Foods, were indicted Thursday by a federal grand jury on price-fixing charges. (Agri Stats was not mentioned in the indictments.)

As Agri Stats finds itself at the center of price-fixing conspiracy allegations, it maintains a low profile. Its website is simple, its social media presence is minimal and its nondescript office sits in a business park in Fort Wayne, Indiana.

That’s the nature of Agri Stats, which “has always been kind of a quiet company,” then-company president Blair Snyder said in a 2009 meeting with a poultry producer’s shareholders. (Snyder’s brother, Brian, now occupies the role.)

“There’s not a whole lot of people that know a lot about us obviously due to confidentiality that we try to protect,” he said. “We don’t advertise. We don’t talk about what we do.”

Data not seen ‘anywhere else in other industries’

Agri Stats reports, when discussed in court documents and among experts, seem almost mythical. Some people have seen portions of them, some people know some people who have seen portions of them.

The reports are widely utilized. In that 2009 meeting, Snyder said about 97% of the poultry industry and 95% of the turkey industry were working with Agri Stats. While he didn’t offer a number on pork industry participation, Snyder called the companies “pretty much a list of who’s who” in swine.

Even the federal government has used the company’s data.

While the terms of the contract aren’t perfectly clear, the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service, or APHIS, has purchased data from Agri Stats over the last decade—something that surprised MacDonald, who worked in a different area of the USDA.

“Wow,” he said when asked about the government’s purchase orders. Because of meat production’s concentration and buy-in from the biggest companies, “Agri Stats is this industry statistics source in a way that you don’t really see anywhere else in other industries,” he said.

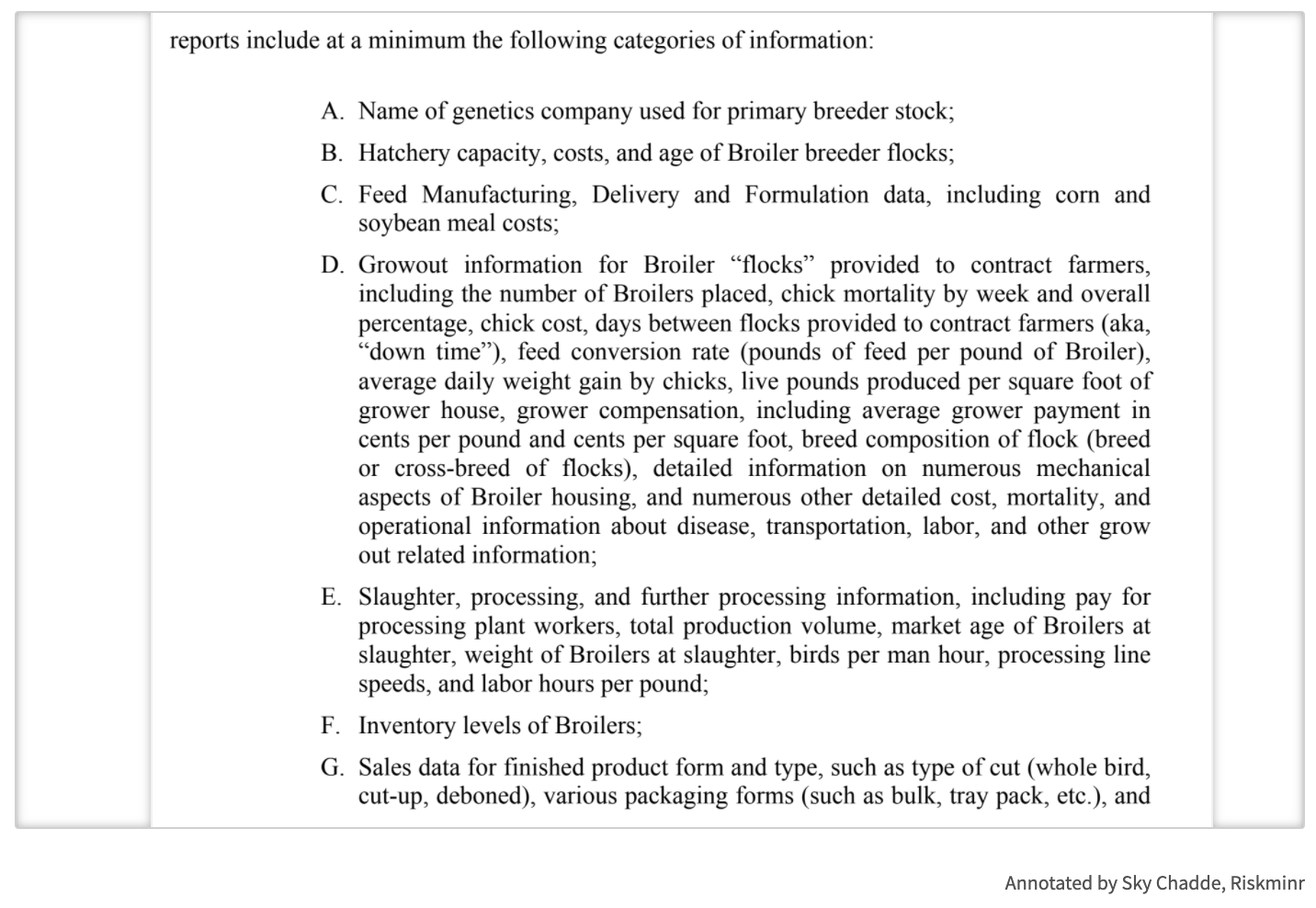

Poultry lawsuits also allege reports contain information on chick placements, various cost metrics, inventory levels, sales data and processing plant worker pay.

An APHIS spokesperson said the department purchased data to calculate indemnity values for poultry should animals need to be euthanized due to a disease outbreak.

“Agri Stats was chosen as a data source for APHIS to calculate the fair market value for various types of poultry because some of these animals are not commonly bought and sold on the marketplace, so price data is not publicly available,” the spokesperson wrote in an email.

But that rather niche information seems to be only a little bit of what’s included in the reports. Elusive as the specific contents may be, court documents outline some of the believed metrics within Agri Stats reports.

Pork litigation court filings allege there were nine sections to reports in 2009, which included animal feed composition, how many animals were at various stages of production and profit margins—essentially information on all aspects of meat production.

Poultry lawsuits also allege reports contain information on chick placements, various cost metrics, inventory levels, sales data and processing plant worker pay.

Agri stats report categories. Link to document here.

Investigate Midwest

(Information distributed by Agri Stats on wages has also been the target of litigation. Pilgrim’s Pride agreed to a $29 million settlement in a wage-fixing lawsuit that includes Agri Stats as a defendant.)

Reports go down to the plant level—even breaking down different sections of a single plant, like labor and supervision within a processing step, Snyder said.

It’s this degree of detail that’s used as evidence of the alleged price-fixing scheme.

“That’s the kind of information no rational competitor would reveal to its competitors, unless it was reciprocated with an understanding that we’re going to use this to control production,” Carstensen said.

Pork suits argue—and the company itself agrees—that Agri Stats’ role wasn’t just to distribute data, but to help participating companies learn from it, too.

“We constantly get asked on an airplane, somebody will say, ‘Blair, what do you do?’ I work in the poultry industry. ‘Well, do you pluck chickens?’ Well, sometimes I feel like I do.”

“The information provided by Agri Stats was so detailed,” the 2020 pork lawsuit reads, “that clients frequently requested the site visits by Agri Stats employees to assist the co-conspirators in understanding the intricacies and implications of the data. Agri Stats’ employees each possessed expertise in a specific area of production, and the value added by their insights was as important to the producers as the data in the books.”

In his 2009 call with shareholders, Snyder alluded to how closely the company works with industry producers.

“We constantly get asked on an airplane, somebody will say, ‘Blair, what do you do?’ I work in the poultry industry. ‘Well, do you pluck chickens?’ Well, sometimes I feel like I do,” he said.

Agri Stats also serves as an internal performance metric for some producers’ employees, not just an indicator of efficiency or profit.

“Every Monday morning we begin our work week talking about Agri Stats,” Sanderson Farms CEO, Joe Sanderson, said in a 2009 investors meeting. “Our operational goals for the year are based on Agri Stats. Half of our bonus of the year … are based on Agri Stats.”

Sanderson Farms did not respond to questions about its current relationship with Agri Stats and whether bonuses are still calculated based on its reports.

How the past can control the future

Part of Agri Stats’ defense against antitrust claims is that data provided in reports is historical, not a forecast. But even some historical metrics can be helpful in monitoring competitors’ participation in a price-fixing scheme when delivered with the nearly real-time nature of Agri Stats’ services, experts said.

Chick placement, MacDonald said, is especially important to a potential scheme: That metric indicates how many chickens there will be down the road. In a price-fixing agreement to keep production low, he said, that’s valuable.

“Knowing this and having this information allows me more assurance that my rivals are cooperating with me,” MacDonald said. “Timely information on production at individual complexes or processing plants is, I think, really crucial to doing that stuff.”

Agri Stats does forecasting work through a subsidiary company, Express Markets.

“Express Markets and EMI Analytics was formed to be able to solve that part of the equation which is talking about what’s going on with agriculture, commodity production, with supplies,” Snyder said during the 2009 call. “It is a very more fact based modeling type process that allows us to put our neck on the line and say we think this is what’s going to happen in the future.”

“Information is not all evil. But what these guys were doing was generating the kind of information in a format that allowed anybody who knew the industry—this at least are the allegations and I’ve not seen any real denial—anybody in the industry is going to be able to really see which plant is which.”

Confidentiality is also key to Agri Stats’ pitch. Its mission statement mentions “preserving the confidentiality of individual companies,” even while providing plant-by-plant information.

In reports, according to the lawsuits, that means company names are stripped from plant information and replaced with numbers. A company can see which plants are its own, but—theoretically—can’t identify competitors.

Lawsuits also spelled out a number of ways the system allegedly fails to maintain confidentiality: Reports are sometimes sent to the wrong company, revealing a competitor’s numbers—which aren’t changed—and plants. It could be possible for some experts to decipher plants based on data alone.

“Information is not all evil,” Carsentensen, the professor and antitrust law expert, said. “But what these guys were doing was generating the kind of information in a format that allowed anybody who knew the industry—this at least are the allegations and I’ve not seen any real denial—anybody in the industry is going to be able to really see which plant is which.”

Then there was a revolving door of employees.

“Agri Stats knew that the anonymity of its system was compromised by individuals who had gleaned knowledge of competitors’ identification numbers, but reassigning numbers was an arduous undertaking the company was not eager to embark on.”

Alaska’s complaint alleges that employees moved both from Agri Stats to participating companies and vice versa. According to their LinkedIn profile, one current Agri Stats vice president joined an Agri Stats subsidiary company from a kettle cooking processor, left to direct sales for a poultry producer, then rejoined Agri Stats. (The company did not respond to a request to speak with the executive.)

Those employees bring knowledge of confidential information as they go, a degree of familiarity with client companies’ operations that Sanderson, the poultry CEO, brought up in the 2009 investors meeting.

“Blair (Snyder) and his company know more about Sanderson Farms than anybody else,” he said, “and Blair knows about all the other companies that are in Agri Stats.”

The pork lawsuit argues a bottom line: “Agri Stats knew that the anonymity of its system was compromised by individuals who had gleaned knowledge of competitors’ identification numbers, but reassigning numbers was an arduous undertaking the company was not eager to embark on.”

Link to document here.

Investigate Midwest

Could courts set a standard for data sharing?

There may well be more lawsuits and settlements, but the complaints—and Agri Stats’ role and function—point to some legal debates.

Then-judge Sonia Sotomayor’s 2001 opinion in Todd v. Exxon is quoted in the pork filing as one standard for determining whether an information exchange between competitors is legal: “Another important factor to consider in evaluating an information exchange is whether the data are made publicly available. Public dissemination is a primary way for data exchange to realize its procompetitive potential.”

Carstensen, who at one time worked as a trial attorney with the DOJ’s Antitrust Division, praised that opinion, but he wants more clarity to come from courts.

“You really need to say, ‘Here’s the kind of information that can be exchanged through a neutral third party in ways that homogenize it so that you can’t tell who’s doing what.'”

“You really need to say, ‘Here’s the kind of information that can be exchanged through a neutral third party in ways that homogenize it so that you can’t tell who’s doing what,’” he said.

That requires setting a boundary somewhere along the information-sharing spectrum, Carstensen said, because he’s sympathetic to the need for some data sharing, too.

“On the other side, it’s terribly important for businessmen to have some idea of what the hell’s going on in the market,” he said. “Why? Because I’ve got to have some idea of what the stuff (I’m selling) is worth. I really have no idea unless I’ve got some sense of the market … I need that information.”

But, Carstensen concludes, “Agri Stats was not producing that.”

UPDATE: This story was updated after publishing to include the news that four of Pilgrim’s Pride’s executives were just indicted on price-fixing charges.