In one of his final acts completing a historic tenure as governor, Terry E. Branstad last week commuted the execution sentence delivered earlier by the Iowa Legislature for the Aldo Leopold Center for Sustainable Agriculture at Iowa State University in Ames. Branstad agreed to allow no funds for the center, but he did not dissolve it as the legislature wished. In that sense, Branstad did not shame Iowa for one of its most celebrated native sons. We can be grateful yet disappointed that we are starving the innovative research that explored how to farm sustainably for profit.

It is appropriate to consider Aldo Leopold. He was a native of Burlington who went on to become America’s leading voice for conservation from the University of Wisconsin at Madison. His A Sand County Almanac stands in the great lexicon of American conservation philosophy with Walden Pond by Henry David Thoreau. While Thoreau was a Massachusetts idealist, Leopold was very much the Iowa pragmatist who tried to figure out how humans could live industriously within the landscape and not spoil it. That’s what the Leopold Center is about.

Lesser known is a collection of Leopold’s essays in a book The River of the Mother of God (1938). You won’t find it at the Storm Lake Public Library, sadly. One would think anything by Aldo Leopold, Ruth Suckow or other great Iowa rural polemicists would be in the stacks, but this is Iowa after all. We prefer to become familiar with other peoples’ history, if any at all.

Two essays stand out, recommended by a friend months ago: “The Farmer as Conservationist,” and “Engineering and Conservation.”

He offers us food for thought as Iowa continues its struggle to move agriculture forward. Looking to our past reveals our future. Leopold wrote of the very same issues eight decades ago.

“The Mississippi dams involve a more subtle issue. That the great river is sick all will agree. Treatment can be applied either to the channel where the symptoms are most conspicuous, or to the deranged watershed which gives rise to the symptoms. The engineers start to bandage the channel with steel and concrete before giving ear to the question of what ails the organism as a whole. The case of course involves many other issues which I do not here discuss. I point out merely the seeming assumption that skillful structures can solve our water problems, and (by implication) exempt us from the penalties of bungling land use.”

The Iowa Voluntary Nutrient Reduction Plan drafted at Iowa State University without consulting the Leopold Center scientists embraces the notion of skillful structures saving us from ourselves, that we can re-engineer the northern Iowa landscape to accommodate that which puts us out of balance. But to every action there is a reaction, as anyone who took high school physics should remember.

“I mention last what to me seems the least discussed but most regrettable instance of short-sighted engineering — the wholesale straightening of small rivers and creeks. This is done to hasten the runoff of local flood waters, and of course aggravates the piling up of flood peaks in major streams. It is, on its face, a process of pushing trouble downstream, of seeking benefit for the locality at the expense of the community. In justice the stream-straightener should indemnify the public for damage; in practice I fear the public may at times subsidize him with relief labor.”

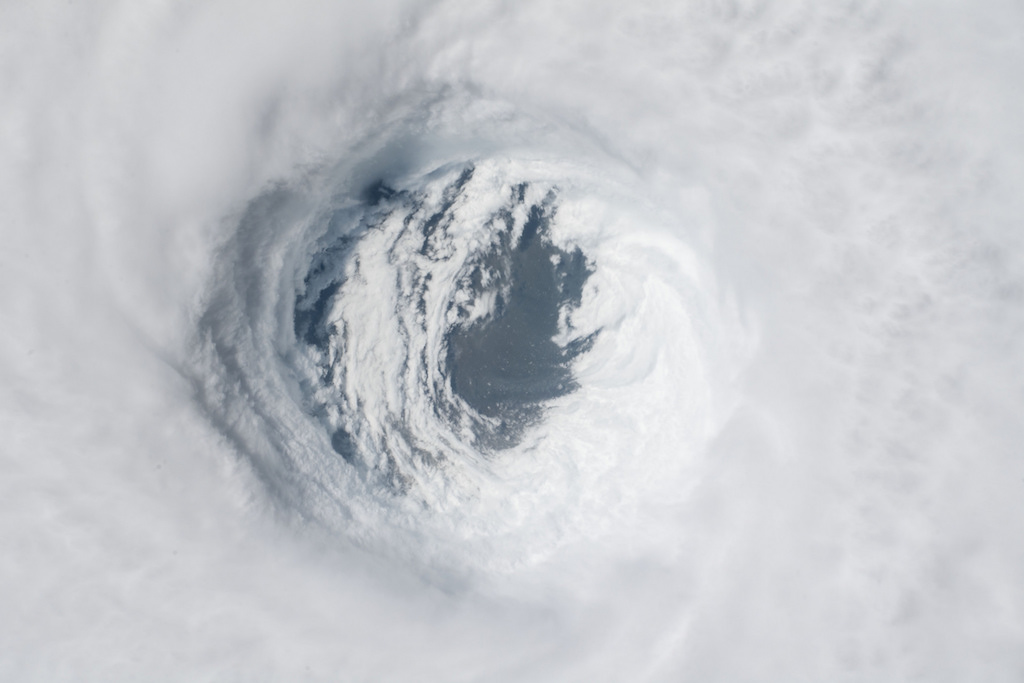

Isn’t that why Cedar Rapids has a 500-year flood every 10 years? Isn’t that why the Des Moines Water Works sued Buena Vista, Calhoun and Sac counties over nitrate pollution of the Raccoon River? Isn’t that why there is a dead zone depleted of oxygen in the Gulf of Mexico, a hypoxia the size of the state of Connecticut, and growing? And isn’t that why the Rock River near Luverne, Minn., has no aquatic life and was declared functionally dead last year by the State of Minnesota?

“I admit, too, that the engineer is not the only focus for biological discontent. The chemist scattering new comforts with one hand and new pollutions with the other, evokes in us the same disquiet. Both professions exemplify priority for the synthetic over the natural, a certain atrophy of esthetic discrimination, a yearning for prosperity and comfort at any cost. I do not claim that we, the disaffected, disdain the prosperity and the comforts. Our only contribution to the idea that the cost is large, unnecessarily large.”

The monarch butterfly is in peril with the bumblebee that pollinates our crops. And so are Marathon and Laurens and Pickerel Lake and Rush Lake and Mallard and Havelock and Maple Creek and Hanover. And all the aspirations that led to their demise die with it.

“When land does well for its owner, and the owner does well by his land; when both end up better by reason of their partnership, we have conservation. When one or the other grows poorer, we do not.

“Few acres in North America escaped impoverishment through human use. If someone were to map the continent for gains and losses in soil fertility, waterflow, flora and fauna, it would be difficult to find spots where less than three of these four basic resources have retrograded; easy to find spots where all four are poorer than when we took them over from the Indians.”

When the first white surveyors found Storm Lake in 1854, it was clear and blue, lined by cobblestones and surrounded by spongy marsh. When my father-in-law started farming at St. Joe along the Des Moines River, it was a community with a school and grandmothers helping mothers maintain a home and grandfathers helping sons plant and harvest. It is gone but for the church and the elderly. Every late summer Hanover invites us to rediscover what we lost with its festival.

“Look, for example, at the eroding farms in the cornbelt. When our grandfathers first broke this land, did it melt away with every rain that happened to fall on a thawed frost-pan? Or in a furrow not exactly on contour? It did not; the newly broken soil was tough, resistant, elastic to strain. Soil treatments which were safe in 1840 would be suicidal in 1940. Fertility in 1840 did not go down river faster than up into crops. Something has gone out of order. We might almost say that the soil bank is tottering, and this is more important than whether we have overdrawn or underdrawn our interest.”

Soil erosion and lake sedimentation have increased exponentially since 1980, according to Iowa State University research, much of it generated by the Leopold Center. We did not want to hear about it in 1940, either.

“It is the individual farmer who must weave the greater part of the rug on which America stands. Shall he weave into it only the sober yarns which warm the feet, or also some of the colors which warm the eye and the heart? Granted there may be a question which returns him the most profit as an individual, can there be any question which is best for the community?”

Iowa was a community. Terry Branstad says there is a war underway between rural and urban, between farmer and water consumer, between capital and the land. Leopold said this:

“He is reminiscent fellow, this farmer. Get him wound up and you will hear many a curious tidbit of rural history. We will tell you of the mad decade when they taught economics in the local kindergarten, but the college president couldn’t tell a bluebird from a blue cohosh. Everybody worried about getting his share; nobody worried about doing his bit. One farm washed down the river, to be dredged out of the Mississippi at another farmer’s expense. Tame crops were over-produced, but nobody had room for wild crops. ‘It’s a wonder this farm came out of it without a concrete creek and a Chinese elm in the lawn.’ This is his whimsical way of describing the early fumblings of ‘conservation.’”

The people of Iowa wanted to bury Aldo Leopold and strip him of recognition at Iowa State University, the first people’s land-grant university for agriculture, research and extension. Terry Branstad couldn’t go quite that far. He is keeping the name around to make us think we learned something from 80 years ago. But there will be no money spent on the prattle he put up, in the way an Iowan might think about it today. You cannot farm without Monsanto and Dow-DuPont. But you can do just fine without Aldo Leopold. You don’t even need him in your library anymore. That’s how we think today.

As he said,

“We end, I think, at what might be called the standard paradox of the 20th Century: our tools are better than we are, and grow better faster than we do. They suffice to crack the atom, to command the tides. But they do not suffice for the oldest task in human history: to live on a piece of land without spoiling it.”