Olivia Box

Returning to my parents’ home in the wake of Covid-19, I learned how intense a compost routine could be.

I felt lazy this morning and dumped my coffee grounds in the trash. They were still warm, slightly gummy from the pourover my brother had just made. The grounds fell from the reusable filter, landing on top of the layers of multi-colored plastic in the trash can. Inky black and baby-warm, they looked quite out of place amongst the taffy-colored Market Basket bags and the clear cellophane wrap that had been covering the peppers.

I knew my careless behavior was wrong.

I knew it was wasteful to dump coffee grounds in the trash when they could have been used to fertilize our fruit trees. I knew about the crisis of crowding landfills and the pounds of perfectly good food that went to waste each day. But I did it anyway. I proceeded to close the trash lid and make my own cup of coffee, then joined my Zoom meeting for Sustainability Science, a class I help teach. The irony is not lost on me.

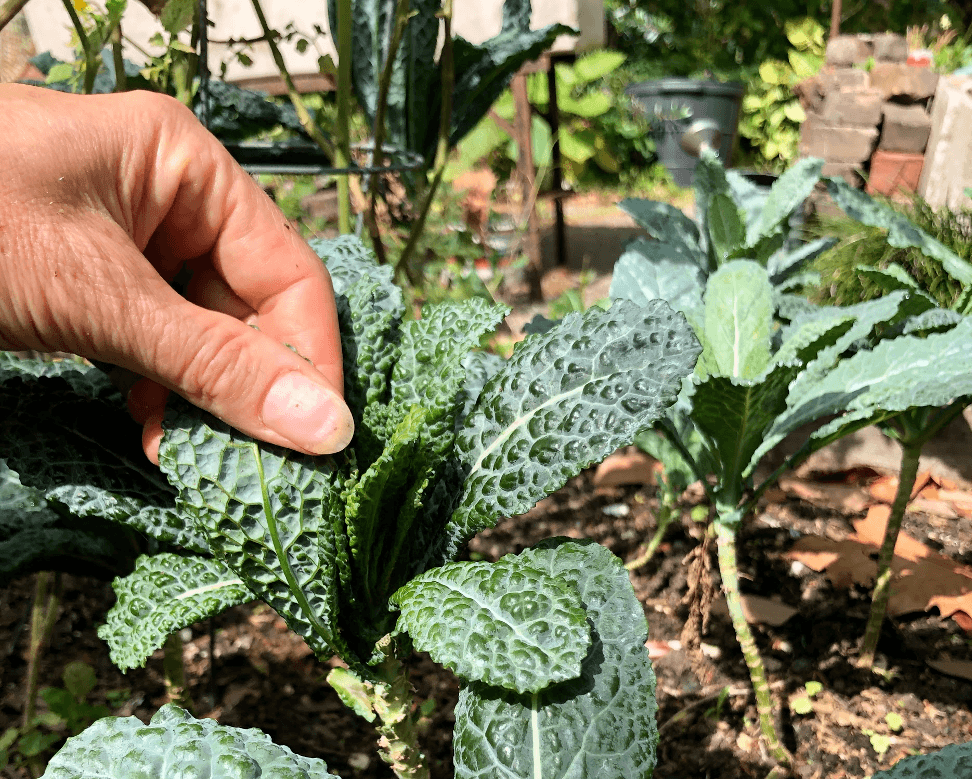

The author’s family’s rigorous composting provides nutrients to the soil and food for their chickens.

Olivia Box

Covid-19 made me feel like I couldn’t be both safe and sustainable. In a more eco-conscious era of my life, I lived in a co-op named “The Beet” and ate a primarily plant-based diet sourced from a Trader Joe’s dumpster. It felt like overnight I had to switch back to single-use plastic and disposable masks.

In my life before the pandemic, I was a graduate student studying forest ecology, running statistical models, and writing about climate change. I ate local, protested often, and complained even more. I thought of myself as progressive and eco-conscious, but returning to my parents’ home in the wake of Covid-19, I remembered how intense a compost routine could be.

Some families go to the Cape in the summer, some love New England sports. We’re the kind that has three different composts: a bin for the chickens, one for the organic garden, and another for the acidic-loving blueberry bushes.

I thought of myself as progressive and eco-conscious, but returning to my parents’ home in the wake of Covid-19, I remembered how intense a compost routine could be.

All our crumbs have their place.

“Who eats banana peels?” my older brother asks my dad. “Chickens!” my dad replies.

“Orange peels?” I ask. “Blueberries love ‘em,” he responds, not missing a beat. The compost fills up quickly and the chickens are happy.

Expiration dates—like most dates now, really—seem not to matter in the time of quarantine. The red lettuce gets weepy, so we wrap it in a towel and let it recuperate in the fridge. The half-and-half curdles a bit in my coffee, and I swish it with a fork, ignoring the chunks that linger. I pick a piece of shell out of my eggs and take it to the appropriate compost bin—for the garden, of course. Having a place for everything makes me feel like I have some sort of control, and I feel less like a hypocrite.

It is a form of self-care for me. It lets me contribute to things bigger than myself: our garden, chicken nutrition, decomposition, and regrowth.

The compost almost offsets my guilt when we unwrap our bimonthly ordered groceries from their plastic bags and disinfect the packaging with Lysol. Then, we throw the plastic bags and Lysol wipes away. Good luck decomposing, I think, as I take off my gloves and dump them, too, into the trash.

Moving back in with my parents has felt unnatural after years of independence, but composting has not. It is a form of self-care for me. It lets me contribute to things bigger than myself: our garden, chicken nutrition, decomposition, and regrowth. Plus, in my family, it’s pretty much mandatory.