courtesy of Jamie O'Connor

Salmon fishing brings in $700 million each year to this remote, sparsely populated area. But with only 15 hospital beds and limited medical resources, local tribal leaders are wondering: Are the risks worth it?

Usually Ronalda Angasan sees her family once a year, during the two months she spends fishing in the Bristol Bay region of Alaska each summer. She grew up there, so like the sockeye salmon she’s aiming to catch, her own internal homing device tells her it’s time to return for a ritual that has been vital to the lifeblood of Alaska for millennia.

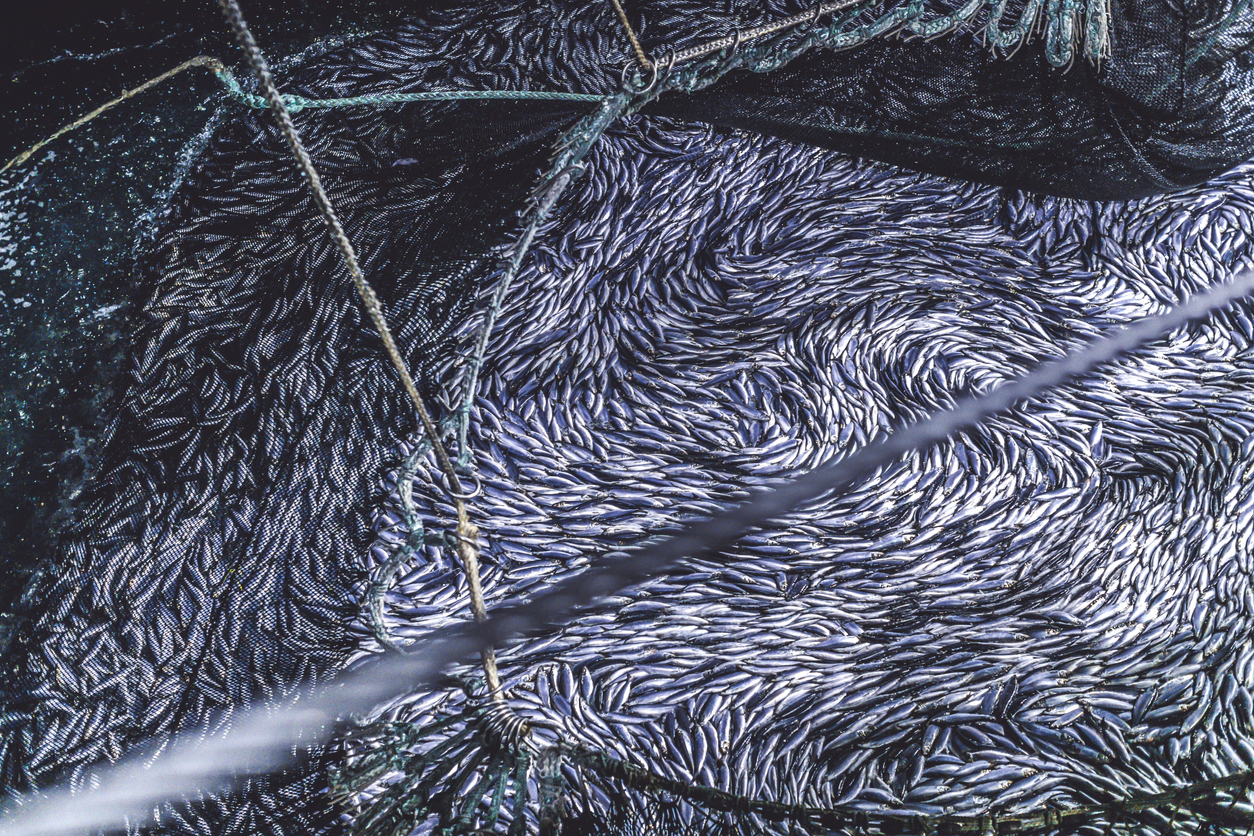

Pictured above, Jamie O’Connor, a fisherman and the Working Waterfronts Director for the Alaska Marine Conservation Council, has spent recent weeks helping to educate and prepare her fellow fishermen for the new risks they face.

This year, even though she’s only miles away from her parents and extended family, she likely won’t see them. Angasan, her husband Brad, their son and two crew members will spend the bulk of the season sequestered in their boat. She doesn’t want her home community of Naknek, Alaska, to worry about her crew being potential carriers of Covid-19.

Located in the southwestern region of Alaska, the 21 rural communities that make up Bristol Bay are only reachable by boat or plane. Spread across a region roughly the same size as Virginia, the total population tops out at just 6,700 people, the majority of whom are Alaska Native.

In Bristol Bay, Alaska the majority of the estimated 12,000 seasonal fishery workers coming to the region are planned to arrive on a rolling basis over the next few weeks

Jamie O’Connor

Even as many parts of the U.S. grappled with spiking coronavirus infections and deaths over the past two months, the Bristol Bay region didn’t have a single Covid-19 case until May 16, just weeks before most fishermen will hit the water for the commercial fishing season. A seasonal employee of Trident Seafoods tested positive after completing a mandatory two-week quarantine. While the state is confident that the worker didn’t transmit the disease locally, residents are worried. The bulk of the estimated 12,000 seasonal fishery workers coming to the region are slated to arrive on a rolling basis over the next few weeks, with the fishing season starting in mid-June.

Residents are concerned that the influx of workers will bring new cases of the virus to their normally isolated communities, and some leaders have debated whether to allow the fishery to open at all, citing the overall risk and lack of hospital capacity. But the fishery, which produces 40 percent of the global wild sockeye salmon catch and is valued at over $700 million after processing, is a vital economic driver of the region.

More than one-sixth of the local population works on the boats or in the factories, making the fishing industry the area’s biggest employer.

Yale said if they get even 10 serious Covid-19 patients, the hospital would be at capacity.

In April, Alice Ruby, the mayor of Dillingham, the largest community in Bristol Bay, and Thomas Tilden, the First Chief of the Curyung Tribal Council, wrote a letter to Alaska Governor Mike Dunleavy asking that he consider closing the Bristol Bay commercial salmon fishery for the season.

In the letter, the duo said that the processing plants that operate in their community will bring thousands of workers to and through Dillingham.

“We must consider that we have limited medical resources in rural Alaska (and all of Alaska); including within the Bristol Bay region,” the letter stated. “We must decide now whether those resources should be devoted to current residents or instead to a temporary labor force?”

The following day, Linda Halverson, President of the Naknek Native Village Council, home to the bulk of the Bristol Bay canneries, sent the governor a letter adding that the Tribal Councils she oversaw stood with Dillingham. “Our people and our culture are at risk,” if the season continues, the letter said. Hospital leaders at the Bristol Bay Area Health Corporation also called for the closure of the fishing season and residents have recalled stories of the 1918 flu that decimated the region, wiping out as much as half the local population in some communities.

More than one-sixth of the local population works on the boats or in the factories, making the fishing industry the area’s biggest employer

Jamie O’Connor

Since the letters, Governor Dunleavy has issued a series of safety measures aimed at preventing the novel coronavirus from taking root in fishing communities across the state, including mandatory testing, requiring captains and managers to make exhaustive plans, and a two-week quarantine for arriving fishermen and processing plant workers.

“We’re doing our best to put in place a management program that will minimize risk to everyone,” said Alaska Department of Fish and Game Commissioner Doug Vincent-Lang, adding that the program includes protocols for what to do if the virus does take root.

Many of the processing companies intend on quarantining employees at hotels in Anchorage before flying them to Naknek and Dillingham on chartered flights. Fishermen, however, have been told to quarantine on their boats.

“This year is different. We’re not going to have that back-up plan of running to the store. This will be a big change.”

It isn’t clear how quarantines will be enforced. At present, the state’s policy is that anyone entering Alaska, resident or otherwise, needs to quarantine for two weeks upon arrival. But, the quarantine mandate has thus far relied on voluntary cooperation. No one in the state has been cited or arrested for breaking the two-week quarantine mandate.

Ronalda Angasan said her crew is taking it exceedingly seriously, with plans to quarantine in both Anchorage and then again in Bristol Bay. But for Angasan, forgoing the season isn’t an option. She and her husband bought a new boat last year and are required to make a $50,000 payment on it at the end of the season.

Because her five-person crew plans on extreme social distancing, Angasan is currently working on making a shopping list for the entire two months.

“Every year, no matter how much coffee I bring, we run out and usually we’re able to pull up to the dock to get more,” Angasan said. “But this year is different. We’re not going to have that back-up plan of running to the store. This will be a big change.”

Jamie O’Connor usually spends the entire season working and camping on a beach with other crews, a concept that will drastically change this year.

Jamie O’Connor

Ten-patient capacity

Even with fishermen and processors willing to make big adjustments, Lee Yale, Chief Nursing Officer at Kanakanak Hospital in Dillingham, is worried.

Kanakanak is the lone hospital in the region. Usually their summer concerns are treating crush injuries and removing wayward hooks. At present, the hospital has just 15 beds and two ventilators, though they’re trying to remodel a former nursing home to add an extra 20 beds in case of a surge in Covid-19 cases. Hospital officials plan to medevac the hardest-hit patients to Anchorage, over 300 air miles away.

Yale said if they get even 10 serious Covid-19 patients, they’d be at capacity. While the state plans to open a screening center by the harbor in the coming days, Yale is concerned it won’t be enough.

Social distancing could prove hard for fishermen and processors. By nature, their roles set up prime conditions for a virus to spread through close contact.

“They keep saying ‘test, test, test,’ but that test is only good for the moment,” Yale said. “Today you could test negative. But the next day you could be positive and not know it.”

At present, the hospital only has a few dozen tests on hand, though the state has supplied 8,000 tests for the harbor site and has plans to send another 8,000 in two weeks, Yale said. That system is able to test 16 people per hour, though should any test be positive, it needs to be sent to Anchorage for verification, a process that takes about a day.

Alaska so far has the fewest infections of any state, with 402 confirmed cases, 36 of which were active as of May 21. The state was ranked as the third most aggressive in terms of limiting exposure, largely due to early adoption of social distancing guidelines and quarantine rules.

But social distancing could prove hard for fishermen and processors. By nature, their roles set up prime conditions for a virus spread through close contact.

Unlike chicken and beef plants, where the employees go home each day, cannery workers stay in big communal bunk houses.

While in the two-week quarantine, most of the fishermen will stay in the harbor. The marina is similar to a car parking lot, with the vehicles resting inches apart. And even onboard, there often isn’t much space to move around—usually the crews share a cramped sleeping quarters.

The processors at the 24 canneries spend much of their days working on a line, similar to the ones at meat processing facilities that have been hit hard by outbreaks of the disease. But unlike chicken and beef plants, where the employees go home each day, cannery workers stay in big communal bunk houses.

The fishermen-funded Bristol Bay Regional Seafood Development Association (BBRSDA) has recently developed a response team to try to mitigate potential outbreaks. It ordered thousands of Buff-brand headbands to be used as masks and are providing boats with two flags: the Lima, Peru, flag, to be flown when they’re quarantining and the Quebec, Canada, flag to fly when they’re in the clear. The association also worked to provide discounted medevac insurance.

“There are a lot of people who have a very strong incentive to keep people healthy as best they can and keep this fishery happening,” said Gunnar Knapp, a retired University of Alaska, Anchorage, professor who taught courses on the economy of fishing in Alaska.

The Alaska Department of Fish and Game is predicting a harvest of 34.6 million sockeye salmon in Bristol Bay this season

Jamie O’Connor

A vital industry

The fishing industry is a key driver of Alaska’s economy. It’s expected to be a boom year—the Alaska Department of Fish and Game is predicting a harvest of 34.6 million sockeye salmon in Bristol Bay this season.

The Bristol Bay is arguably the most valuable wild salmon fishery in the world. Sockeye salmon usually makes up more than half of the state’s total salmon value and Bristol Bay rakes in more than two-thirds of Alaska’s sockeye. During peak season in July, millions of salmon are harvested each day. It’s a frenzied time, with fishers and processors working up to 20 hours per day.

In 2019, the initial Bristol Bay catch was worth over $300 million, though the value of the salmon increases at each stage of the distribution chain. By the time it’s processed, it’s price has risen to over $700 million.

Closing fisheries could cause a domino effect that would topple an industry valued at $5.6 billion, a devastating loss.

According to a study by the Institute of Social and Economic Research at University of Alaska, Anchorage, co-written by Knapp, for “every dollar of direct output value created in Bristol Bay fishing and processing, more than two additional dollars of output value are created in other industries, as payments from the Bristol Bay fishery ripple through the economy. These payments create almost three jobs for every direct job in Bristol Bay fishing and processing.”

The state’s other two leading industries, oil and tourism, have taken big blows due to Covid-19, in the forms of crashing oil prices and cancelled cruises and vacations. Closing fisheries could cause a domino effect that would topple an industry valued at $5.6 billion.

“Everyone is working really hard to make sure this goes well, but only tomorrow will tell,” Yale said.

A test run in Cordova

Cordova, Alaska, nearly 500 miles away in south-central Alaska, is the first fishery in the state to open in mid-May each year. Though Cordova’s operations are significantly smaller, Bristol Bay is anxiously watching to see how the early days of that season play out.

Within a few days of staff arriving, it was announced that one processing worker in Cordova tested positive for Covid-19 despite quarantining and testing negative in Anchorage. Officials rushed to isolate that individual and tested all who came in contact with him. They now consider the case to be contained, though it is still unclear how that person became infected.

“We’re certainly not going to jeopardize public health unnecessarily,” said Vincent-Lang. “We will study closely what we’re seeing and observing in Cordova and will take the appropriate actions moving on. Right now, we’re going to put the infrastructure in place to be able to manage the Bristol Bay fishery, if we can conduct it in a safe and healthy manner. I’m pretty confident, based on what I’m seeing in Cordova, that we’re going to be able to have those fisheries.”

“We’re going to follow the mandates and social distance and practice good personal hygiene and really just hope for the best.”

Bristol Bay will see more than triple the number of newcomers that Cordova does. It’s estimated that the bulk of non-Alaskans working in Bristol Bay (one-third of the fishermen and two-thirds of processors) come from California, Oregon, and Washington, some of the states first hit by the coronavirus. At present, five non-resident seafood workers have tested positive for Covid-19 across the state.

Hoping for high numbers of fish but a low number of infections has proven to be a common thread for the fishermen planning to return to Bristol Bay this year.

“We’re going to follow the mandates and social distance and practice good personal hygiene and really just hope for the best,” fisherman Brad Angasan said.

Jamie O’Connor, a fisherman and the Working Waterfronts Director for the Alaska Marine Conservation Council, has spent recent weeks working to help educate and prepare her fellow fishermen for the season to better improve the odds.

“The future of the season, of our food supply, of the safety of our friends and neighbors is in all of our hands and we have to take this seriously.”

“The future of the season, of our food supply, of the safety of our friends and neighbors is in all of our hands and we have to take this seriously,” O’Connor said. “I’ve been fishing my whole life and this will be a season unlike any I’ve ever seen before. As an industry, we’re going to have to change the way we do almost everything.”

O’Connor said she’s mourning the loss of the pre-season, a period she says is marked by reunions and excitement, as well as the social aspect of fishing. As a set-net fisherman, O’Connor usually spends her entire season working and camping on a beach with other crews (many of whom she’s related to), a concept that will be foreign this year.

But, despite the added hoops, the extra costs and the uncertainty, Angasan and O’Connor said they can’t imagine not participating.

“This is our livelihood, we are fishermen,” O’Connor said. “It is what we do to feed ourselves, it’s what we do to feed the nation. We are an essential piece of our food supply. Local fishermen are depending on that season. It’s not just something we decided to do—these are small businesses that have been built over lifetimes. We’re ready to adapt, but a closure would be devastating.”