Photo by Libby Anderson/Flickr/Nicolas Raymond/Graphic by Talia Moore

A weekly series about one chef who closed three restaurants during the pandemic—and intends to get them back.

Those were the days: It might have been a big birthday or anniversary, a graduation, a promotion, a new job, or just a night when cooking was too much to ask. It might have been a big-city shrine to culinary innovation, a beloved Italian place in a mini-mall, or a tamale cart.

Whatever and wherever it was, we went out to dinner to have a good time. Now most of us don’t. The ones who rushed to do so, well, we’ll see whether that turns out to be a bad move, soon enough. In the meantime, restaurant owners like chef Gavin Kaysen try to define a new dining environment that feels safe, and is still fun, for the larger wait-and-see crowd.

There is no definitive rulebook, no list of absolute protections, so he has taken to reading other states’ guidelines while he waits for Minnesota’s. Governor Tim Walz announced last week that restaurants can re-open on June 1; the meter starts running then on the crucial summer season. Kaysen won’t be part of the first wave, because it seems too little time to get ready. Still, he has to make practical decisions because there are so many to make.

And while the food won’t change much, everything else has to.

Demi’s 2019 spring menu

Demi

Kaysen’s youngest restaurant, the year-old Demi, is likely the first one he’ll re-open, because it’s small—20 seats, compared to over 170 at both Spoon and Stable and Bellecour, whose bakery used to draw lines down the block. And Demi is a controlled environment, with two seatings and an orchestrated set of about 10 courses. Spoon and Stable and Bellecour, with more people at a more irregular pace, will be harder to figure out.

So let’s go to Demi for dinner tonight.

We live our lives artificially and at a distance these days, with family dinners and happy hours on Zoom, doctor’s appointments on FaceTime, and online learning; personal experience is only immediate if you’re quarantined with family or a roommate. In context, a virtual meal at Demi is not really an odd suggestion. Do you have something better to do?

Kaysen is happy to be our host for the evening—or maybe not happy as much as willing to share the bewildering array of choices he faces before anyone can really make a reservation. There will be adjustments from the moment we walk in the door until we walk out again. His refrain, as he considers what a meal at Demi used to mean, step by step, is simple:

“That’s gone.”

—

Photo by Libby Anderson/Flickr/Nicolas Raymond/Graphic by Talia Moore

The untouchables

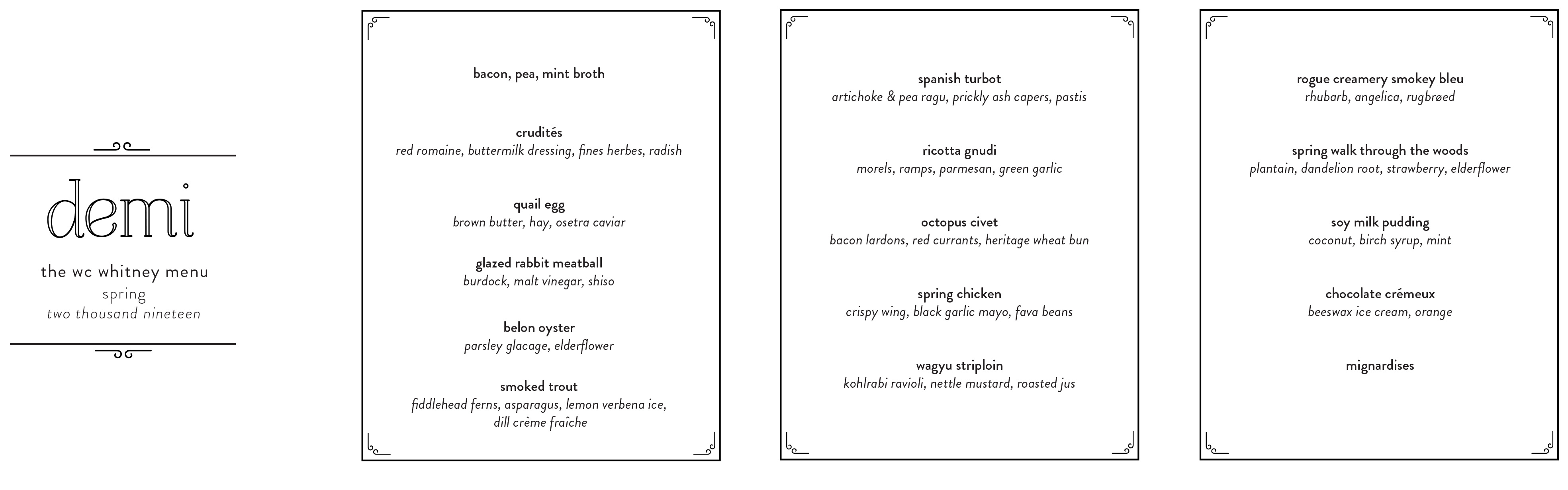

We used to do 40 people on a given night, five days a week. To reopen we can only do 24 people a night, 60 percent occupancy to keep us at six feet of social distancing, but the seating is at a counter. Do we have to put plexiglass up between guests and the kitchen team? They’re less than six feet away, but how is it any different than if you go to a restaurant and someone brings you your plate? Maybe we don’t have to put plexiglass up.

When you walk into Demi you walk into a small space, a bar, a lounge, a living room, really. No menu, no bar menu, no drink menu. You talk to the bartender and host, there are card games if you want to play cards. It’s very interactive: someone wants to know, what do you think you want to drink?

The point to that experience is that we want to remove the idea of expectation. Usually, when you go into a bar or restaurant and you feel uncomfortable, you grab a menu and that becomes your distraction for a moment. But we want to expose that. Don’t worry about this, let’s be uncomfortable and vulnerable together, and while we are, let’s talk about your favorite champagne or gin and we’ll get it for you.

Before the pandemic, Kaysen greeted his guests with a handshake. The bartenders asked guests for their preferred spirits to deliver a personal cocktail or beverage. These interactions will have to change when Demi re-opens.

Libby Anderson

That whole experience has to go away because we can’t put them in this little confined space anymore. What will that look like instead? Can we bring them in in a different way, can we use some outdoor space to bring them in? We have some outdoor space that’s covered and heated for winter, but it’s not that big.

Then they sit down and we bring them a drink.

The next step of service would actually be a welcome, in which we offer a handshake to the guest to greet them. That’s gone. For some people that handshake was a little bit odd, but we’re trying to instill a sense that this is not transactional: what you’re about to be a part of is very meaningful to us and we want it to be meaningful for you. We recognize that it took time to get a reservation, you’re spending hard-earned money to eat here, it’s an expensive meal.

We’ve been talking—masks are great, we’re happy to wear them, but are we better off wearing a face shield? You can see our faces, it’s easier to understand what we’re saying, but I can’t imagine greeting guests wearing a face shield.

We don’t want to start with the mindset of, Hi, my name’s Gavin and I’ll be your server tonight.

And there’s the question of what we’re wearing.I’ve started to read some guidelines. Minnesota’s haven’t come out yet, but yesterday I read California’s guidelines. We’ve been talking—masks are great, we’re happy to wear them, but are we better off wearing a face shield? You can see our faces, it’s easier to understand what we’re saying, but I can’t imagine greeting guests wearing a face shield.

And I don’t know how much heat a plastic face shield can stand.

I just don’t know. I don’t know what’s better.

We used to offer a warm towel. That’s probably gone.

—

Photo by Libby Anderson/Flickr/Nicolas Raymond/Graphic by Talia Moore

The evening meal, or what’s left of it

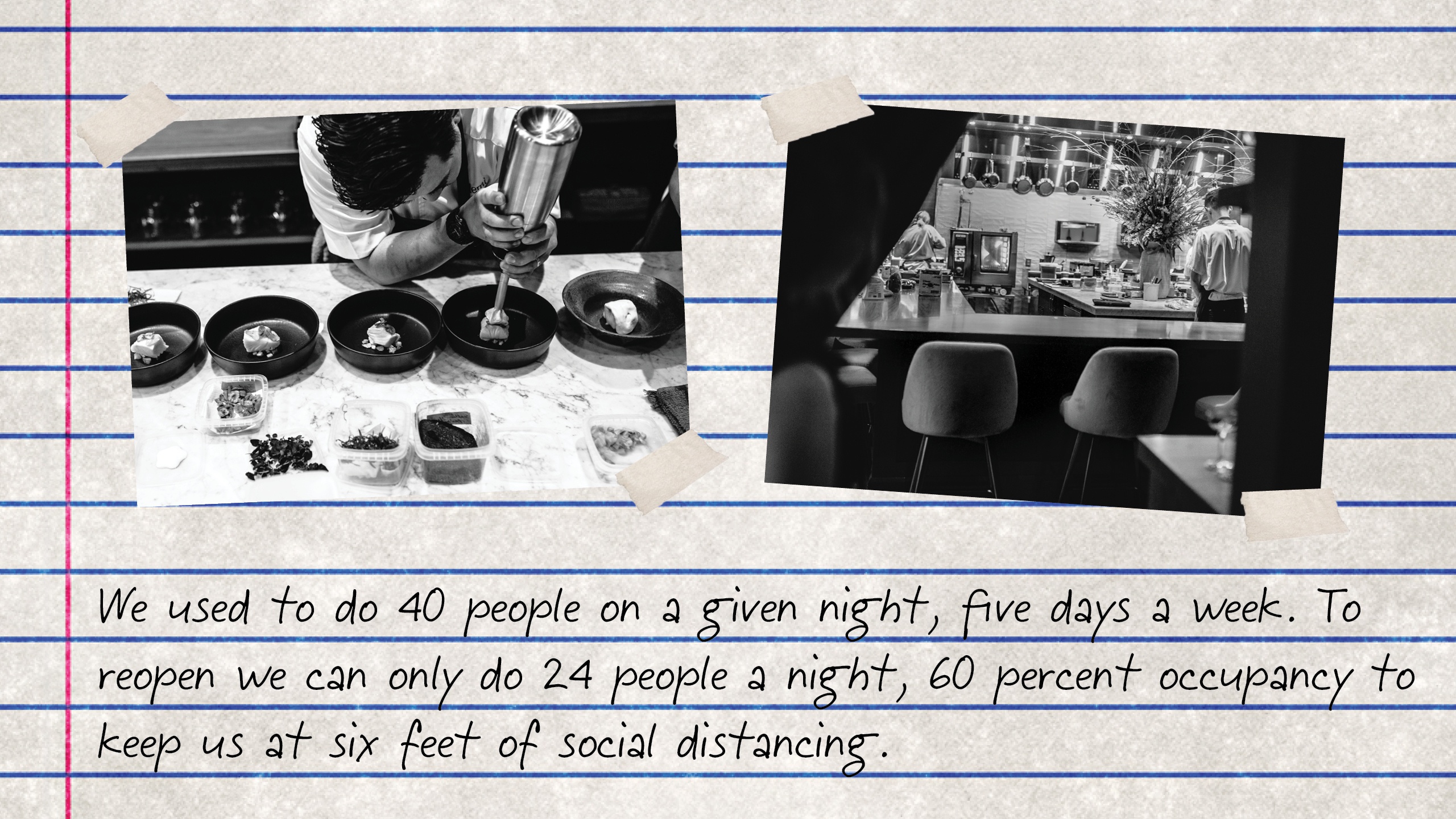

There’s a lot of tableside service: sauces tableside, broth poured tableside, your main course is beef, maybe that’s sliced tableside. All of these fascinating experiences that we think about, and want to direct attention to, and what we’re realizing is that this portion of the experience will likely go away. If it does, how and when do we replace it, and what do we replace it with?

We used to carve the duck tableside, directly in front of you, and if I can’t do that, if I have to carve it in the kitchen, what do I do—or was it always more meaningful to me than to you?

I think part of this is how we perceive it. It’s a comfort level thing: Are the guests comfortable with this now, or not? We don’t know the answer yet. Some of it might be trial and error, until we see how guests respond.

Normalcy’s the wrong word, it won’t be like it was, but I want the feeling that in some ways was a kind of freedom.

One thing with Demi that’s always powerful to me is that when guests come in they allow themselves to leave behind wherever they are in their heads, and just be there. Libby, our communications director, deals with social media, and at a meeting a week or two after we opened she said that we don’t get a lot of social media posts while guests are dining. It’s a day or a couple of days after they eat here, and they do it in a different way. It’s not, Hey, look at me, I’m at dinner at Demi. It’s, If you don’t want to ruin the experience of eating here don’t look at the photos. People are not actively taking tons of photos. They’re there to experience Demi and have a good time.

I wonder how we can capture that again, once people have a desire to go out. Normalcy’s the wrong word, it won’t be like it was, but I want the feeling that in some ways was a kind of freedom.

—

The broth

Libby Anderson

The green mint and pea broth from Demi’s spring menu

The first course would be the warm broth that’s poured tableside into a bowl. I think that would still be okay to do, because the little pot we pour the broth into is for you, the guest, and then it’s brought back to the dishwasher and sanitized and cleaned for the next guest. That would seem to be okay.

But as we go through each of the courses, we’re going to have to pull back on those pourings and preparations, unless they’re specific to that party. If there are 12 people we can seat two deuces and two four-tops. And if we do that, we need to have four sets of everything for those people, one set for each party.

Before, we might only use the pot for two tables, because the broth has herbs or flavorings steeping inside, and after the second round it loses a bit of its power. Now it will have to be one pot for each individual set of guests. This is a bad example, but it’s one everyone can relate to: You’re at a diner and the person who pours coffee stops at your table, pours, and then walks to the next table and pours coffee, and on and on.

That won’t work. That teapot, while it is perfectly safe and sanitary for multiple parties, and nobody’s touching it except me or a cook, might be perceived as not okay.

—

The raw course

The first course would typically be a raw course, raw or slightly cured. We would still do it. I don’t think people would shy away from it. In general, the actual food we cook or serve won’t change that much. It’s more of how it’s served. If we served raw food before, I’d still feel comfortable doing so. We’re just trying to balance the weight of having the guest feel comfortable in the space, or having them feel “enter at your own risk.”

Right now, in Minnesota as in most states, menus already have a note about food that’s raw or undercooked being potentially dangerous, so people are aware of that.

On the service side of things, we normally change out your silverware at every course, and with 10 courses that’s a lot of silverware. We’re not going to be able to do that, most likely. The amount of interaction, of touching, might seem invasive to people. Maybe we’ll build a little box. You open it up, here’s your silverware for the evening, here’s the best way to use it, here’s the sequence.

And let’s say that courses one, two, and three require the same pieces of silverware. After course three we’ll take away the dirty silverware, and you’ll look at your card for your next set of instructions.

Those are the things we’re starting to think through. How do we keep the fun, playful interaction alive? That’s one way. Normally we’d give you the menu at the end of the experience, but now we might package it all up for you right away. You can look at it in advance, and maybe the guest might feel a little more in control of the experience.

—

Photo by Libby Anderson/Flickr/Nicolas Raymond/Graphic by Talia Moore

No more sharing. Maybe.

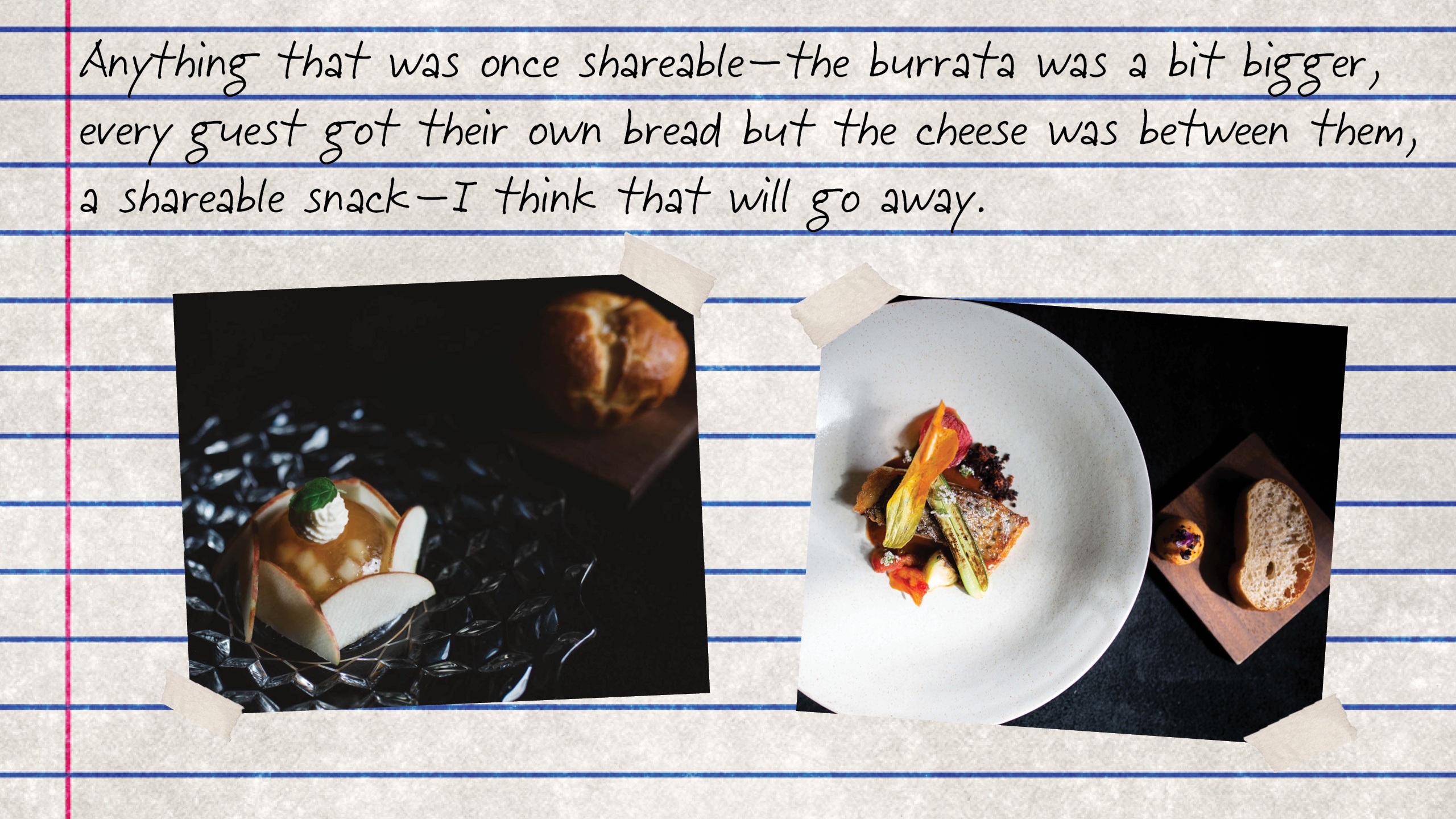

Then there’s always a course, we call it the bread-service course, could be with burrata cheese, or snap peas, or whatever, but there’s a bread component that’s the more substantial part of the course. Typically that’s baked fresh for each guest, and we put it on a little tray for each guest. That won’t go away, that will still live, but anything that was once shareable—the burrata was a bit bigger, every guest got their own bread but the cheese was between them, a shareable snack—I think that will go away. But then there’s the argument that if you’re eating with another person you probably feel safe sharing the burrata.

The bread’s been proofed and prebaked a little bit to hold the structure, but we basically bake the little roll to order, for about 12 minutes, we time it out with the course.

If we serve a brioche bun, doesn’t matter what else you serve that night, could be diamonds on a plate, but people will say, The brioche is the best thing I ate all night. It’s homey, it’s nostalgic, it’s baked just for me, and you can smell it. You walk into the restaurant and once the first set of guests gets that bread, the scent fills the air.

—

The tableside debate

Moving on to the meat course, the protein. The plating of the vegetables is done in the kitchen, we bring that to you at the counter, and then there’s a tray we bring, that my brother made. With it there’s a knife, a little bain-marie with a spoon, a trivet with a sauce pot, and then we bring the protein. Let’s say it’s the bison, on a little cutting board. We slice in front of the guest, wearing gloves, always did that, and then we put on a little fleur de sel and give it to the guest. Now: do we do that in the kitchen or still in front of the guest, and what’s the argument either way?

Many courses at Demi were plated in front of guests, but they may have to be prepared in the kitchen, depending on what makes guests feel most at ease.

Libby Anderson

I think if the guest feels comfortable in the space—because now there are only 11 other people, and there aren’t 100 other people like there are at Spoon and Stable—maybe we continue to slice it in front of them.

—

Guilty pleasure

There are usually two desserts, but those are typically plated so I don’t see an issue there.

For the last portion of your meal you get two things. We present a full tray of petits fours, chocolates and candies Diane has made, we allow you to choose what you’d like off the tray, and then we use wooden tweezers to move them from the tray to your plate. That will likely not happen. We will likely create little boxes for each guest to take these to go.

The most heart-wrenching course for me, which I’m going to try to keep, is our Rice Krispies bars, my favorite guilty pleasure…I don’t know. I’m going to fight for this one, figure out if we can keep it.

The most heart-wrenching course for me, which I’m going to try to keep, is our Rice Krispies bars, my favorite guilty pleasure. Instead of making them ahead of time and cutting them into squares, we make them fresh and they come out still warm, fleur de sel on top, in a little copper pot with two spoons, and we say, “This is chef’s favorite guilty pleasure, we encourage you to enjoy the way he does, just eat it warm right out of the pot.”

I don’t know. I’m going to fight for this one, figure out if we can keep it. It goes back to the broth issue. That pot of Rice Krispies bars is only for you, nobody else gets it, so it should be okay. Maybe we give everyone their own pot, we have enough of them, instead of two people sharing.

I just think it’s a chance to have fun, to experience all of what we’re missing, that human connection. So I’m trying to think it through. We want to do the right thing, but part of the difficulty is that we don’t have clarity about what that is, about everything, not just what to eat.

—

Photo by Libby Anderson/Flickr/Nicolas Raymond/Graphic by Talia Moore

Data-driven dinner

When you have a friends-and-family dinner, when a restaurant’s opening up, those people leave a comment card. Yes, you just got a free meal, but tell us, what do you think? Maybe we should start to think about that now, with all our guests: get some feedback, where is their confidence, what are their concerns, even if it’s just the first three or four weeks. That might be enough data to pull together a sense of where everybody feels comfortable.

When we all first open again we’re going to be opening based on assumptions. We obviously don’t have the intention of doing the wrong thing, our every intention is to do the right thing, but we have to figure out what that is. If we can gain even a week’s feedback, once we open, that’ll help us understand. We want to be cautious, not to blow this out of proportion but to make people feel safe and secure.

With Demi, we could even send that card before they dine. You get a confirmation of your reservation four days in advance and maybe there’s a little questionnaire with it, five questions, very specific, to give us a sense of where you are as a guest. We can alter the interaction based on that. Demi is so controlled. At Spoon, you have walk-ins, but maybe you could do it a little bit, get some information.

Everybody has such a different perception of what to do, and that’s where it gets tough. So many perceptions change. It’s a tough balancing act.

At Spoon, the shared plates will all go away. There aren’t that many, a section on the menu with three to five dishes that were shareable. But a lot of people, if they were a table of four to six, would each order an appetizer and a main course and then order two or three pastas as a middle course, to share.

That revenue stream will likely change unless we can come up with a different way to prepare and serve the pasta. Maybe people ordered that way because an appetizer size was too big for one person? Maybe we have to have three tiers of sizes now.

Are we having fun yet?

I was talking to someone who told me that up until recently they would cook the salad they got for takeout. “I’d order a salad and take it home and cook it to kill the virus,” they said. Everybody has such a different perception of what to do, and that’s where it gets tough. So many perceptions change. It’s a tough balancing act.

I should’ve asked what kind of salad. I hope at least it was a kale salad. That would’ve been a little better.