In mid-May, the beaches and skies over a three-mile swath of southern New Jersey swarm with birds from the end of the world. Tens of thousands of intrepid travelers flecked in grey and salmon descend on the sandy shores and tidal flats of the Delaware Bay for a massive feeding party that can last several weeks. The annual visit is an essential stopover for the tiny-feathered visitors, shorebirds called red knots, which travel the length of the globe twice each year in what is one of the longest migrations of any animal in existence.

The red knot spends its winters along the vast and rocky beaches of Tierra del Fuego, the southern tip of South America. Each February, flocks set off on a 9,300-mile journey to the Canadian Arctic. The birds make only a few stops along the way, spending several days foraging in Brazil before pressing ahead to North America, where, for another several weeks in May and June, they blanket a small area of the Delaware Bay to bulk up on the eggs of horseshoe crabs. Reinvigorated from their nutrient-rich snack, and with their body weight nearly doubled, the birds then embark for the icy Arctic, where they spend the summer before undertaking the return journey to South America in the autumn.

Red Knots can fly up to 4,000 miles before stopping to feed, and they often soar at a height of twenty thousand feet along their eastern seaboard route. “Surely the red knot is the most spectacular migrant of all,” wrote naturalist and ornithologist Roger Tory Peterson of the bird’s staggering yearly journey.

But the red knot, named for its salmon-hued chest, has fallen on hard times in recent decades: Climate change has eroded its habitats and chipped away at its food sources. The population of red knots wintering in South America dropped about 75 percent from the mid-1980s to 2003, according to the Audubon Society and U.S. Wildlife officials. They are now listed as a federally threatened species in the U.S.

In New Jersey, overfishing of horseshoe crabs and dramatic changes to the shoreline, due in great part to massive storms like 2012’s Superstorm Sandy, have left the birds’ coveted eggs in shorter supply. The population of North American red knots stands at about 140,000, experts have estimated.

Now, conservationists and federal and state wildlife officials say, the endangered bird has a new threat in New Jersey: Oysters.

In the past several years, the Garden State’s once-thriving oyster industry has experienced a resurgence, with about a dozen oyster farmers setting up businesses in the same muddy, nutrient rich waters where the red knots pursue crab eggs.

Oyster farmers have scrambled to locate along a seven-mile stretch of the Cape May peninsula because the salinity, mineral content and other conditions are so amenable to delicious, healthy oysters called “Cape May Salts.”

“There’s really nothing like these oysters,” says Stephanie Cash, who opened the Dias Creek Oyster Company with her husband Richard during their retirement years. “The taste profile, the merroir…. Our customers are head over heels for us.”

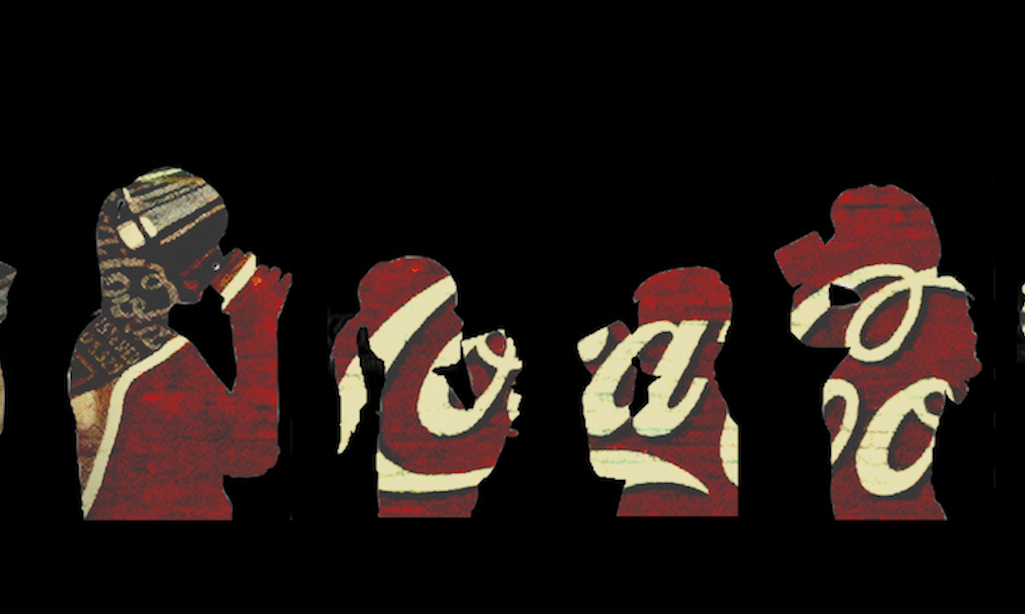

Red knots flock to the Delaware Bayshores to feed on horseshoe eggs

But oyster farmers like Cash say their work, and profits, have been slammed by unnecessary restrictions aimed at keeping beaches clear of humans and aquaculture equipment while the red knots visit each spring. Conservationists maintain that the birds are frightened by human presence in their feeding grounds and the racks, boats and equipment farmers use have made it hard for the red knots to forage—pushing them closer to extinction.

To minimize the human-bird interaction, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Services this year instituted new rules that ban farmers from reaching their oysters for the two hours before and after high tide, each morning and evening, from May 1 to June 7. In addition, they are banned from farming activities on weekends.

Cash, who produces a nutty, creamy delicacy she dubbed “Venus oysters,” says her original farm location off a rocky beach in Cape May County “has essentially been condemned.”

“They (conservationists) are working to preserve this bird that needs to be preserved…and that’s good. But the lengths to which they are carrying this would meet every one of the five criteria of junk science. They are alarmist in a way that’s not science. They are looking with a bias toward a certain finding,” she says.

The debate presents a special challenge for federal and state regulators working to protect the unique bird from extinction while promoting oyster growing, a sustainable and green source of jobs and revenue.

“We are playing Solomon in this,” says Larry Hajna, spokesman for the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection, “We’ve spent many years trying to protect the red knot and many years trying to restore the oyster industry.”

The growth of aquaculture and ecotourism in southern New Jersey has been seen as a tonic for a region that has suffered numerous financial blows, with sinking fortunes in Atlantic City and higher-than-average unemployment and crime rates in cities like Camden and Trenton.

Horseshoe crabs migrate to the Delaware Bay around the same time as the Red knots

Oyster champions, like Mike De Luca, the director of Rutgers University’s Aquaculture Innovation Center, says growth in the state’s south is now pinned to developing aquaculture, eco-tourism and other environmentally-sustainable sectors, with many of those opportunities presented by the 780-square mile region around the Delaware Bay, an estuary outlet of the Delaware River into the Atlantic Ocean.

“I firmly believe that shellfish farming is perhaps one of the greenest industries on the planet,” De Luca says. “They are filter eaters, so they clean the water. They also provide structure, or habitat, for other fish and shellfish.”

Cape May Salts are cultivated using a rack-and-bag method, a system widely used in France. The oysters are placed in mesh bags tied to a steel rack in the tides, usually reachable only by foot. The oysters are carefully tended until they grow to market size, and the bags are power washed to rid them of non-harmful Polydora worms that might gather on the surface. In what is already an ecologically sound industry , the rack-and-bag system has minimal environmental impact, supporters say.

Last year, nearly 1.5 million Cape May Salts were sold to restaurants and markets—up from 100,000 just 15 years earlier. But Cash and other oyster farmers believe they could be farming far more bivalves if their work was not restricted during key harvesting weeks in the late spring. Last year, Dias Creek Oysters produced 10,000 oysters in what Cash calls “an extreme regulatory environment.”

“It’s been frustrating, to say the least,” she says.

De Luca says information is still lacking on how the birds will react to the human presence in their Delaware Bay feeding ground. “With better science information, obviously, we’ll be able to guide the expansion of the industry better. I really believe co-existence is possible here,” he says.

Many Cape May oysters are cultivated using a rack-and-bag method, which has minimal environmental impact but can also prevent the crabs from reaching the beach to lay their eggs

Tim Dillingham, executive director of the American Littoral Society, says that argument is “misleading.”

“There’s plenty of science out there, and it’s all been made available to the industry by the Fish and Wildlife Service’s work, that shows that when the operators are out on the racks several times a day, that disturbs the birds away from their feeding on the foraging grounds.”

Dillingham added that the racks also prevent the crabs from reaching the beach to lay their eggs.

“We’d like to see the industry accommodated. But the aquaculture industry wants to expand into critical habitats that are vital for the protection and recovery of these shorebirds. And they wanted to do so in the times that the birds are there in a manner that would have created harm to the bird’s survival,” he says.

De Luca believes one possible solution to the red knot versus oyster controversy could rest in deep water.

“If we really want to see some broad expansion of the industry, we are most likely going to be looking for subtidal waters, which has been a popular practice in other areas of the world,” he says.

According to De Luca, deep water Shellfish farming in the Delaware would come with challenges. Farmers would need to use boats and other heavy gear to access their stocks, while the winds, currents and wave conditions of the bay are often hostile.

The oyster beds in Cape May are largely reachable on foot. Oyster farmers may need to move into deeper waters in order to expand

The New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection says both federal and state agencies are using an adaptive approach to protect the interests on both sides. “Essentially we are seeking balance,” Hanja says.

Oyster farmers, some clinging for survival, have organized cooperatives to share processing facilities and boats and to step in and help fill orders when stocks fall short. Cash says the red knot regulations, along with a dizzying catalog of 12 other agencies to which the farmers must report, has made for some unlikely relationships.

“The truth is, this whole experience has brought us closer to our regulators,” she says.

For Dillingham, the debate has an easy solution: Simply ban oyster farming from the small stretch where the birds feed.

“What’s unfortunate about this is that it’s really an argument we don’t need to be having,” he says. “There are a couple of operators who want to operate in the red knot habitat. Rather than relocate, which may have some cost to them or inconvenience, they chose to make this argument.”

“We are talking about an endangered species. Extinction is forever. Once this bird is gone, it’s gone.”