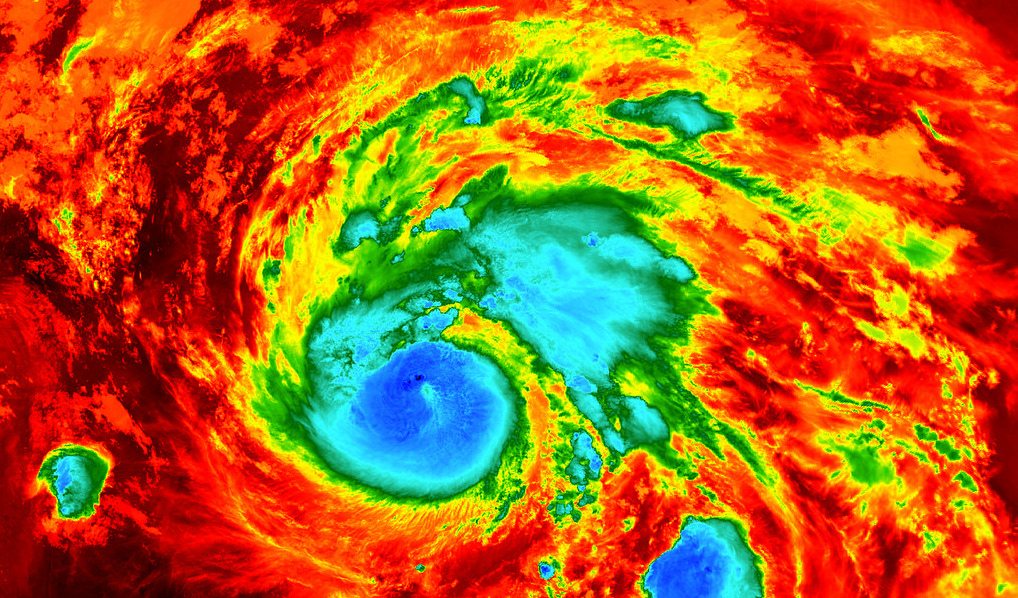

By now, Houston-related headlines are rising as quickly as the rainfall totals are. And you surely know the facts: Late last week, Tropical Storm Harvey developed into a Category 4 hurricane, colliding on Friday night with Southeast Texas near Corpus Christi, and then hovering—parking, really—over Houston and its surrounding areas. Four days later, the result of Harvey’s slow and soggy wrath, now moving east into Louisiana, is what the National Hurricane Center has called “ongoing and catastrophic life-threatening flooding.”

And still the rain falls.

But Texas, home to the country’s fourth-largest city, is also home to the most cattle, sheep, and goats in the nation. It also leads the United States, according to the Texas Department of Agriculture, in number of farms and ranches, with nearly 250,000 of them covering 130.2 million acres.

And many of those ranches lie in floodplains. A herd of cattle outside of Dayton, Texas on Monday required a police escort to relocate to higher ground, quickly resulting in a viral video, shot and posted on Twitter by CNBC producer Harriet Taylor. Similar imagery emerged from Bay City, La Grange, and Beaumont.

We can’t yet imagine the full measure of Harvey’s impact on Texas and Louisiana’s agriculture industries—and likely won’t for many weeks and months to come. But we do know this: “The 54 Texas counties declared a disaster area due to Hurricane Harvey contain over 1.2 million beef cows, or more than one-fourth of the state’s cowherd.” That’s according to Blair Fannin of Texas A&M AgriLife Extension, who wrote about the numbers for AgUpdate on Tuesday.

Police moving cattle to higher ground just outside Dayton, TX with team @contessabrewer @CNBC pic.twitter.com/yRuqvahPOw

— Harriet Taylor (@Harri8t) August 27, 2017

AgriLife is coordinating with 59 sheltering sites (many of which are de facto holding facilities) across the state, that have posted their available space on this list. Those spaces include veterinarian’s offices, fairgrounds, show barns, horse shelters, expo centers, and even a church. “Open to Cattle Only—Bring your own Feed, Water, etc. Owner is Solely responsible,” read the listing for Four County Sale Barn, an auction facility in Austin. “Horses and Livestock, Near Capacity, Call Before Going,” wrote the Dimmit County Fairgrounds, located near the southwestern tip of the state.

Just an hour’s drive west of Corpus Christi in Alice, Texas, Eddie Garcia watched the weather forecast closely last week. On Wednesday, August 23, he announced an open-door policy at Gulf Coast Livestock Auction via Facebook, saying he would shelter livestock of all shapes and sizes at his auction house. Water and hay were free of charge. “I just thought it was time to do the right thing,” he said when reached by phone on Tuesday. “You can’t charge people during crisis.” His post was shared more than 900 times.

Most of the people who responded to Garcia’s message were total strangers in need, from nearby Rockport and Corpus Christi. “I had a seventy-year-old lady and some fifteen-year-old girls drop off horses,” Garcia said. Over the last week, his facility has sheltered 60 horses, 50 goats, 30 head of cattle, a couple of donkeys, and one potbellied pig named Penny.

Penny and about half of the horses have already been released back to their respective homes. Garcia said the owners of the remaining animals are likely stranded without water and power. But his auction barn is equipped to hold 2,000 head of cattle, and he’s prepared to take care of the stranded livestock for as long as necessary. “This is a way for me to give back,” he said.

Of course, the vast majority of Texas’ 12 million cattle are probably not being sheltered in auction barns. But not even the industry’s trade groups have a full handle on the situation. In a post on its website, the Texas and Southwestern Cattle Raisers Association wrote that “News about ranchers and livestock in the area affected by Hurricane Harvey has been slim since Friday,” followed by a call for personal anecdotes from members. The association is holding conference calls with relevant government agencies for affected cattle ranchers every afternoon.

Comments on the Cattle Raisers’ website paint a fractured picture of ranchers’ experiences thus far: “Cows were stranded on mound. They swam to me and we put them in the meadow. Feeding out hay,” wrote rancher Pat Leidner. “Please turn off the rain.”

“Lots of cattle have been moved so hopefully livestock losses should be minimal. Flood is predicted to be long lasting so hay supplies may be critical for some,” wrote Coleman Locke of J.D. Hudgins, Inc., a Brahman cattle beef producer in East Bernard, Texas. “We did not have the catastrophic damage that the coastal cities and now Houston is having, but the wind was constant and damaging,” added Audra Schulz, another poster in central Texas, east of San Antonio.

Just as status reports are hard to come by, so too could be post-crisis relief for producers without farm and ranch insurance. Like homeowner’s insurance, farm and ranch insurance will cover personal property in dwellings for those who also live on the land on which they produce. It will also cover farm personal property, like machinery and farm tools. But flood protection is specific to each insurer’s list of qualified “perils,” and riders (or extensions) often need to be added to cover structures and food-producing animals in the event of adverse weather.

The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) and Farm Service Agency (FSA) have a livestock indemnity program (LIP) that provides benefits to cattle, poultry, swine, goat, and sheep producers for livestock deaths “in excess of normal mortality caused by adverse weather.…” And “LIP payments are equal to 75 percent of the average fair market value of the livestock.” The program factsheet lists tropical storms, hurricanes, and floods on its roster of eligible adverse weather events.

The agency has also partnered with the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) to establish a Disaster Resource Center that supplies information on crop and livestock loss. (For a complete listing of USDA disaster assistance programs, click here.)

But before tolls are officially taken, before the flurry of claims are filed, before recovery, and removal, and rehabilitation, there is little to do today but watch the sky and wait for tomorrow to come. There are, after all, many long, wet tomorrows ahead.