The farm bill—the omnibus spending bill that determines the lion’s share of federal food and agricultural policy—is set to expire this year. And Secretary of Agriculture Sonny Perdue on Wednesday unveiled details of the newest iteration, along with a skimpy-on-specifics legislative priority list for 2018. The document doesn’t tell us much, and checks all the expected boxes: Support farmers from economic hardship, protect consumers from foodborne illness.

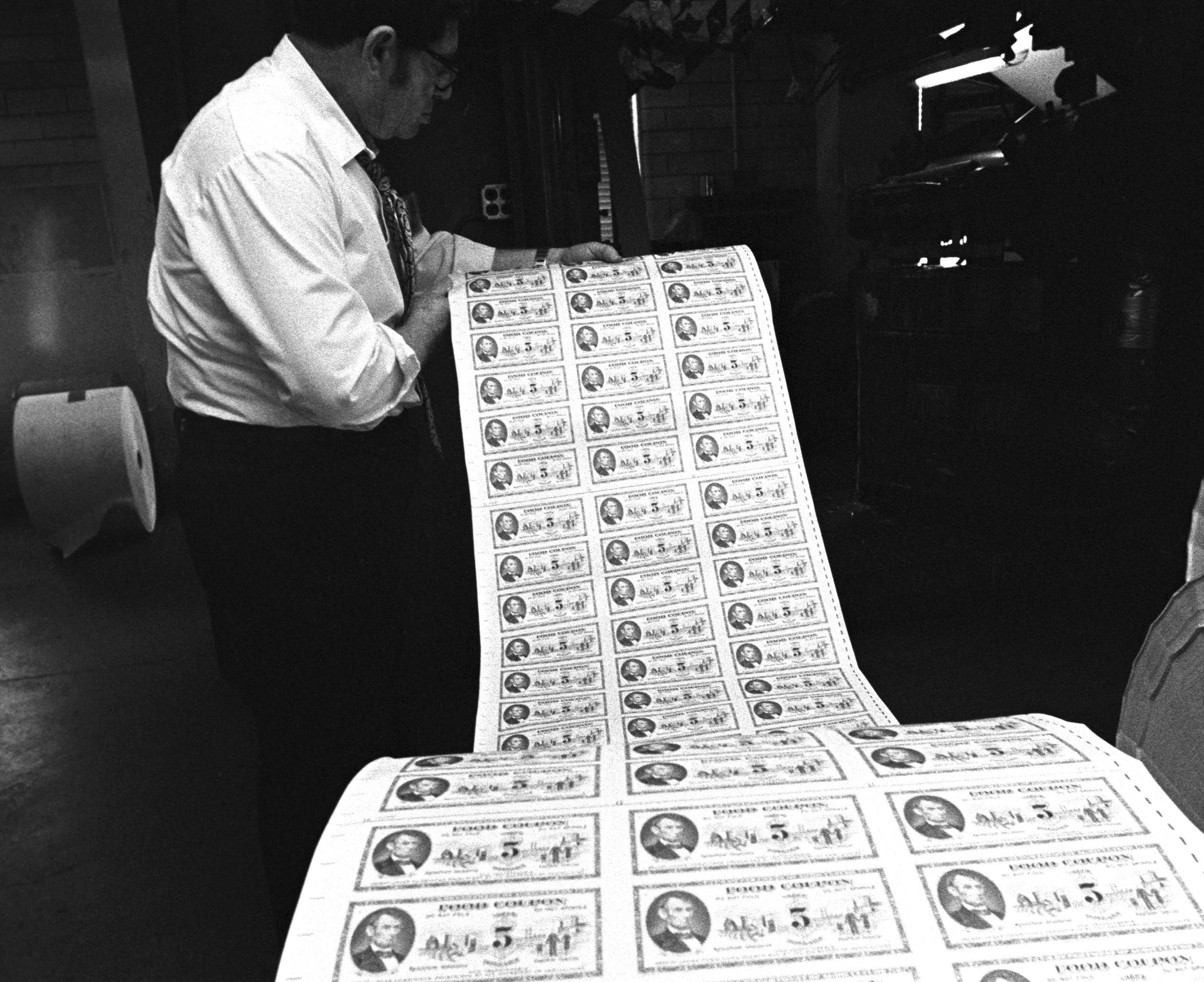

But looking through the document for specific legislative priorities, one line in particular sticks out: a promise to “protect American taxpayers by reducing waste, fraud and abuse” in food and nutrition programs. That phrase alone pretty much guarantees we’ll see some contentious debate over the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP, formerly known as food stamps) in the coming year.

For the record (really, once and for all), let’s be clear: SNAP rules already require that all recipients meet work requirements unless they are a child (duh), a senior, or a person exempt because of a disability. According to the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), those three groups represent two-thirds of SNAP recipients.

But look out for lots of bandying about the acronym ABAWD, “able-bodied adult without dependents,” an especially contentious group aged 18-49 who can only receive benefits for three months in any three-year period. After those expire, ABAWDs are required to work 80 hours a month, participate in job training for the same time period, or do unpaid work under a state-approved program to qualify for benefits.

Some states with particularly high unemployment or an inadequate number of available jobs can apply to waive that restriction for ABAWDs, and more than 40 did just that during the height of the global recession. (The state of Illinois requested and was approved for such a waiver for all of the year 2018, citing high unemployment in a number of counties.) But in the summer and fall of 2017, as the economy continued to improve, a number of states moved to reinstate the work requirements, Tennessee and Alabama among them.

No wonder the Kansas City Star editorial board in May called SNAP “the country’s most misunderstood welfare program.”

As we head into peak farm bill season, there are a couple of things worth knowing. First, SNAP usage has trended steadily down from a post-recession high in 2013 of just over 47 million participants to 42 million in October of 2017—the latest available month of data. Next, Congressional gridlock over the program is all but guaranteed: Democrats strongly oppose cuts (especially after having weathered more than $8 million of them during the 2014 farm bill negotiations) while Republican lawmakers focused on wider entitlement reform will hold the line.

One thing does seem clear: the future of nutrition assistance is anything but.