iStock / fstop123

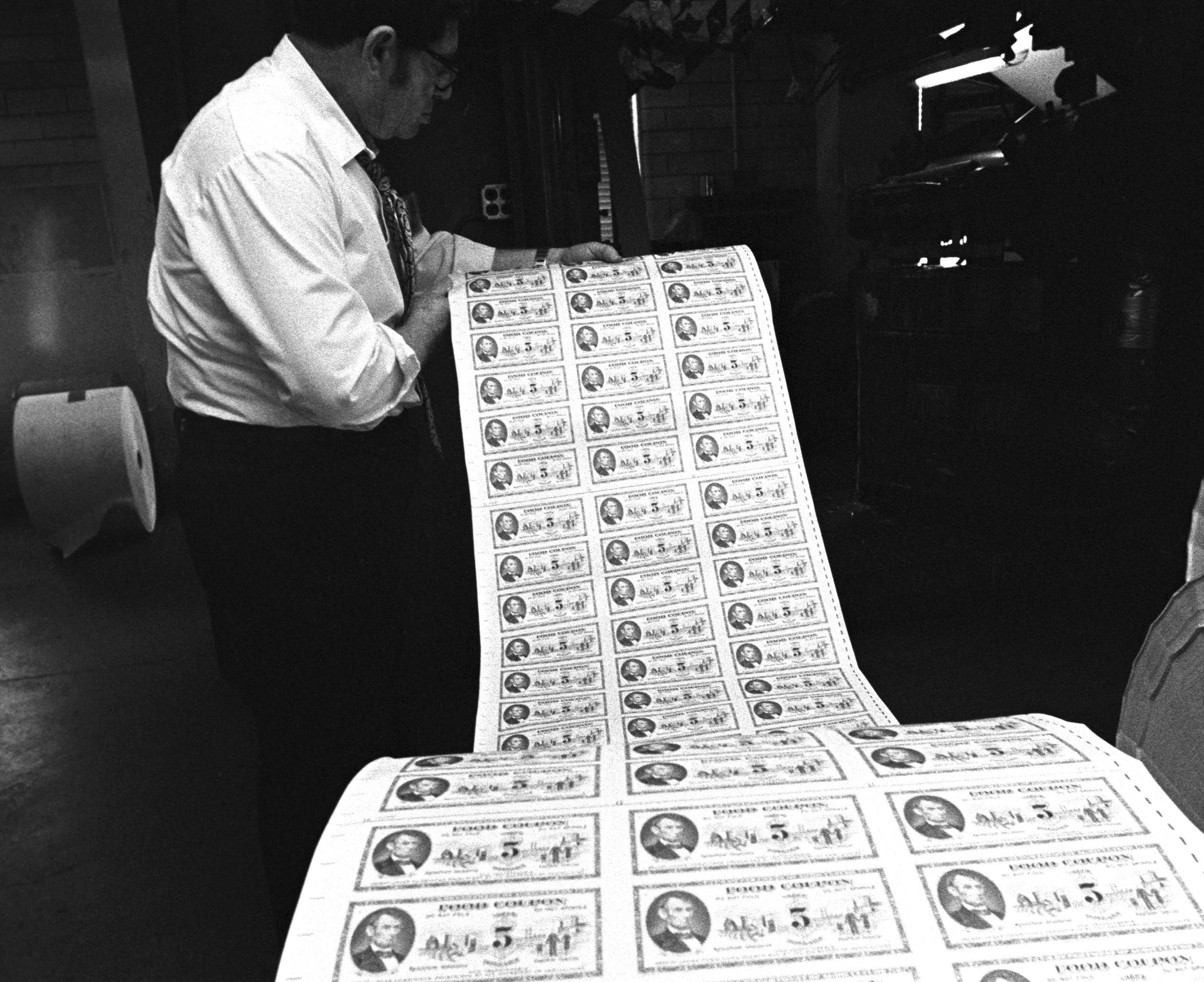

More than half of people who rely on the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP, formerly food stamps) to buy groceries run out of money in the first two weeks after benefits are issued each month, according to the most recent data from the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA). Anti-hunger advocates have long criticized the program’s funding model, arguing that it doesn’t provide a realistic monthly food budget for a truly nutritious diet.

New legislation introduced in the House by Representative Alma Adams, a Democrat from North Carolina, would change that. Adams’s bill proposes an estimated 30-percent increase in the dollar amount of benefits disbursed to each recipient every month, according to the Food and Environment Reporting Network (FERN). New York’s Democratic Senator Kirsten Gillibrand is expected to introduce a companion bill in the Senate.

Right now, all SNAP benefits are determined based on USDA’s Thrifty Food Plan (TFP), a “national standard for a nutritious diet at a minimal cost,” that serves as the basis for maximum food stamp allotments. For 2019, the Thrifty Food Plan budgeted a maximum of $38.30 a week for females aged 19 to 50.

But if more than half of people who rely on it can’t make the TFP last a full month, where did that allotment come from in the first place?

According to Angela Babb, a post-doctoral research fellow at Indiana University who wrote her dissertation on the TFP, the calculation dates back to the 1970s. That’s when Miriam Rodway, a woman from Jamaica, New York, sued USDA, arguing that food stamps weren’t worth enough money to purchase a “nutritionally adequate” diet—a directive of the 1964 Food Stamp Act. The court ruled with Rodway et al., and the agency was forced to rethink the system.

Instead of setting a monthly allotment based on the true cost of a healthy diet, however, USDA created a diet that justified the existing allotment. “The USDA resolved to create a computerized, mathematical program that would set the existing budget, and calculate a diet that met that budget in order to prove that the budget was enough,” Babb says.

Thus, the TFP was born. But even in the beginning, it wasn’t built around recipients’ real food and nutritional needs. A closer look at the numbers reveals that the total allotment is based on some surprising (and frankly weird) assumptions about what people might have to eat in order to achieve a “healthy” diet that also costs them less than $40 a week. On the TFP, it’s suggested that an adult woman, for instance, might need to drink three cups of milk per day. It also lumps meats and beans together into one of the five major food groups.

Babb found other nutritional gaps in the TFP, too. In the most recent USDA analysis of the updated Thrifty “market basket”—a model of suggested food consumption patterns—researchers concluded that most TFP baskets exceeded the Dietary Guidelines for sodium. What’s more, they couldn’t come up with a hypothetical basket that would provide adequate levels of vitamin E and potassium for all age groups.

Babb filed a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request to learn more about the manual adjustments researchers made to the mathematical equation to force it to fit into the existing allotment. “The most outrageous one is they adjust the constraint for females 14-18 so that they’re allowed up to 40 times the [recommended] meat,” she says.

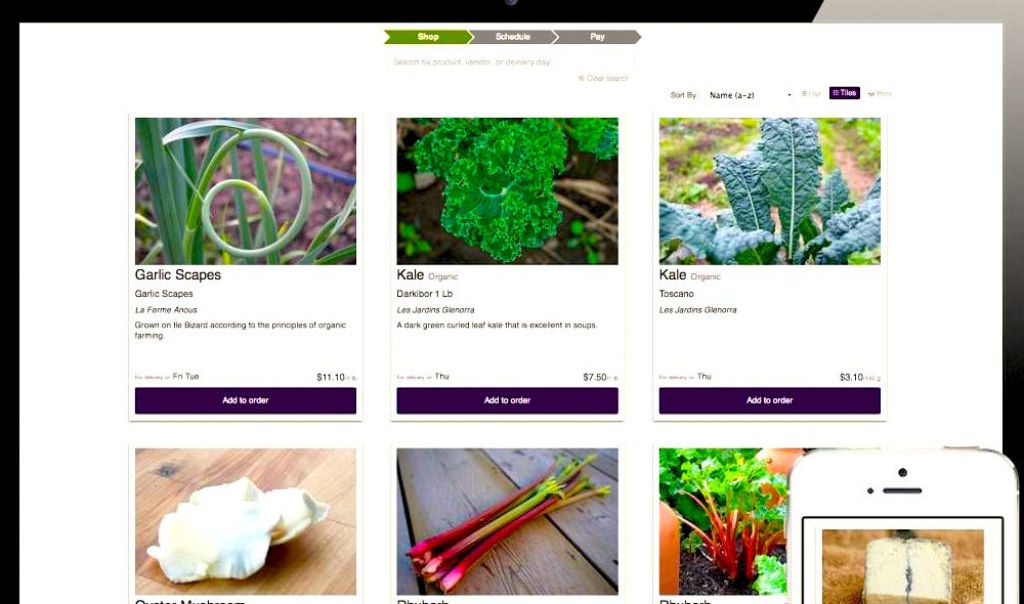

There’s no telling whether Adams’s bill will get any traction in Congress. As FERN reported, she filed similar proposals in the Republican-controlled House with little success. And it’s unclear that the Low-Cost Food Plan would adequately fund nutritious diets across the board, either. MIT’s Living Wage calculator estimates a Brooklyn-based woman needs $290 a month for food, roughly $85 more than the Low-Cost Food Plan allotment.

In the meantime, looks like it’s milk for breakfast, lunch, and dinner for most TFP eaters.