Jessica Fu

On Thursday afternoon, New York City elected officials introduced a first-of-its-kind resolution that, if passed, will call on municipal agencies and the private sector to sever ties with food companies linked to deforestation in the Amazon. Council member Costa Constantinides, Democratic representative for the 22nd district in Queens, announced the proposal on the steps of City Hall against a backdrop of environmental activists. A few hours earlier on the West Coast, a Los Angeles official made a similar plea.

“I hope that we are able to make sure that city agencies and the mayor’s office understand the stakes that are in play here and the necessary nature of what we’re trying to accomplish,” Constantinides said.

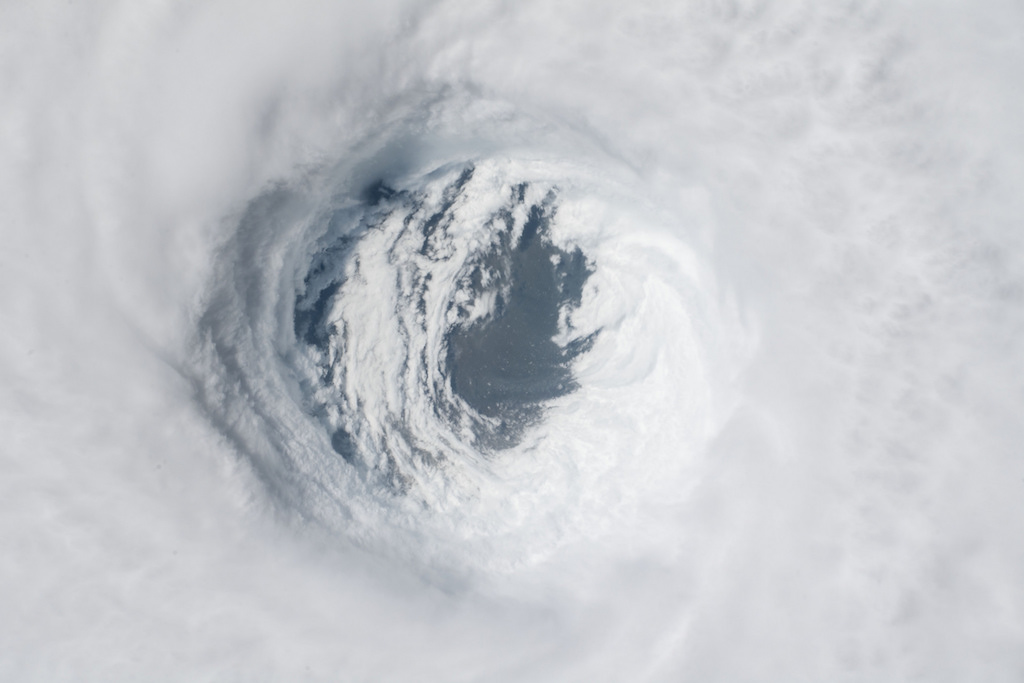

Both pieces of legislation were drafted in response to growing concern about wildfires in the Amazon, the number of which spiked significantly this year, per data from Brazil’s space agency. In August NASA corroborated the findings, noting that the 2019 fires were significantly more intense than previous years. The news raised alarm bells for scientists, environmentalists, and politicians, and drew renewed attention to the crucial role that the Amazon rainforests play in absorbing climate-shifting greenhouse gases. The fires also threatened indigenous tribes whose territories are located in the rainforest.

Council member Costa Constantinides announces a proposal to end ties with food companies linked to deforestation of the Amazon

Farmers in Brazil—which contains a majority of the rainforest—commonly take a “slash-and-burn” approach to production, in which forest vegetation is cut or set on fire to clear land for cattle-grazing or crop production. Brazil’s forest code permits some degree of deforestation in the Amazon, the extent of which varies based on vegetation type. Under President Jair Bolsonaro’s administration, however, enforcement of the code has declined. The economic and policy factors that drive this deforestation are manifold, but the issue is deeply linked with high demand for two of the country’s biggest exports: beef and soy.

If metropolitan cities boycotted, say, Brazil’s beef giants, those companies might be compelled to stop sourcing cattle from deforested land, the bill’s reasoning goes.

“Companies like Marfrig, JBS, and Cargill are some of the main culprits in this issue—we need to cut ties from them,” said Brooklyn borough president Eric Adams, while introducing the motion at City Hall. Marfrig and JBS are Brazil’s two biggest beef processors. Cargill is an enormous American agricultural company that produces foods including beef and soy, some of which it sources from Brazil. (It’s important to note that U.S. officials banned imports of fresh beef from Brazil over food safety concerns in 2017. That could change in the near future. In the meantime, the U.S. continues to import processed beef products like beef jerky and corned beef.)

Unlike laws, resolutions, if passed, form an official position for New York City, which it can then use to advocate for policies at a state or national level. Council members have adopted resolutions on a wide range of issues, from calling on the city’s Department of Education to stop serving processed meat last year, to opposing the Congressional actions that led up to the Iraq War in 2002.

At this time, the proposed New York City resolution does not list companies from which it urges a boycott, nor does it specify any criteria for determining them. To Scott Swinton, a professor of agricultural and environmental economics at Michigan State University, this lack of clarity could render the resolution rather toothless.

An environmental activist holds a sign prior to proposal announcement outside of City Hall

Swinton also noted that New York City is a comparatively insignificant market for Brazilian exports, when compared with the scope of global trade. Meanwhile, the ongoing trade war between the U.S. and China has driven the latter to buy more food from Brazil.

Some advocates believe policymakers would have a better chance at reducing deforestation by giving farmers in Brazil economic incentives to preserve the Amazon. Otherwise, “there’s a perception that the developed world doesn’t want the emerging economies to emerge,” says Daniel Nepstad, forest ecology scientist and executive director of rural development nonprofit Earth Innovation Institute.

Nepstad encourages participation in programs like REDD, which attempt—though not always successfully—to compensate communities for the opportunity cost of preserving forests.

The New York City resolution, which currently has the backing of three council members, can be found here. The Los Angeles resolution can be found here.

We’ve reached out to JBS, Marfrig, and Cargill for comment and will update this post if we hear back.

Update: After publication, a Cargill spokesperson provided the following statement: “Illegal deforestation and deliberate setting of fires in the Amazon is unacceptable, and along with others in the food and agriculture industry, we will continue to partner with local communities, farmers, governments, NGOs and our customers to advocate for approaches to preserve this important ecosystem.” Additionally, the statement cited the company’s participation in the Amazon soy moratorium, a voluntary agreement to not purchase soy harvested on land deforested after 2006.