What’s the value of “authenticity” at a Japanese restaurant? Apparently, a little under $4,000. That’s how much a ramen restaurant in New York City is coughing up after the United States Department of Justice (DOJ) found that its former chef had refused to hire a waiter because he wasn’t Asian.

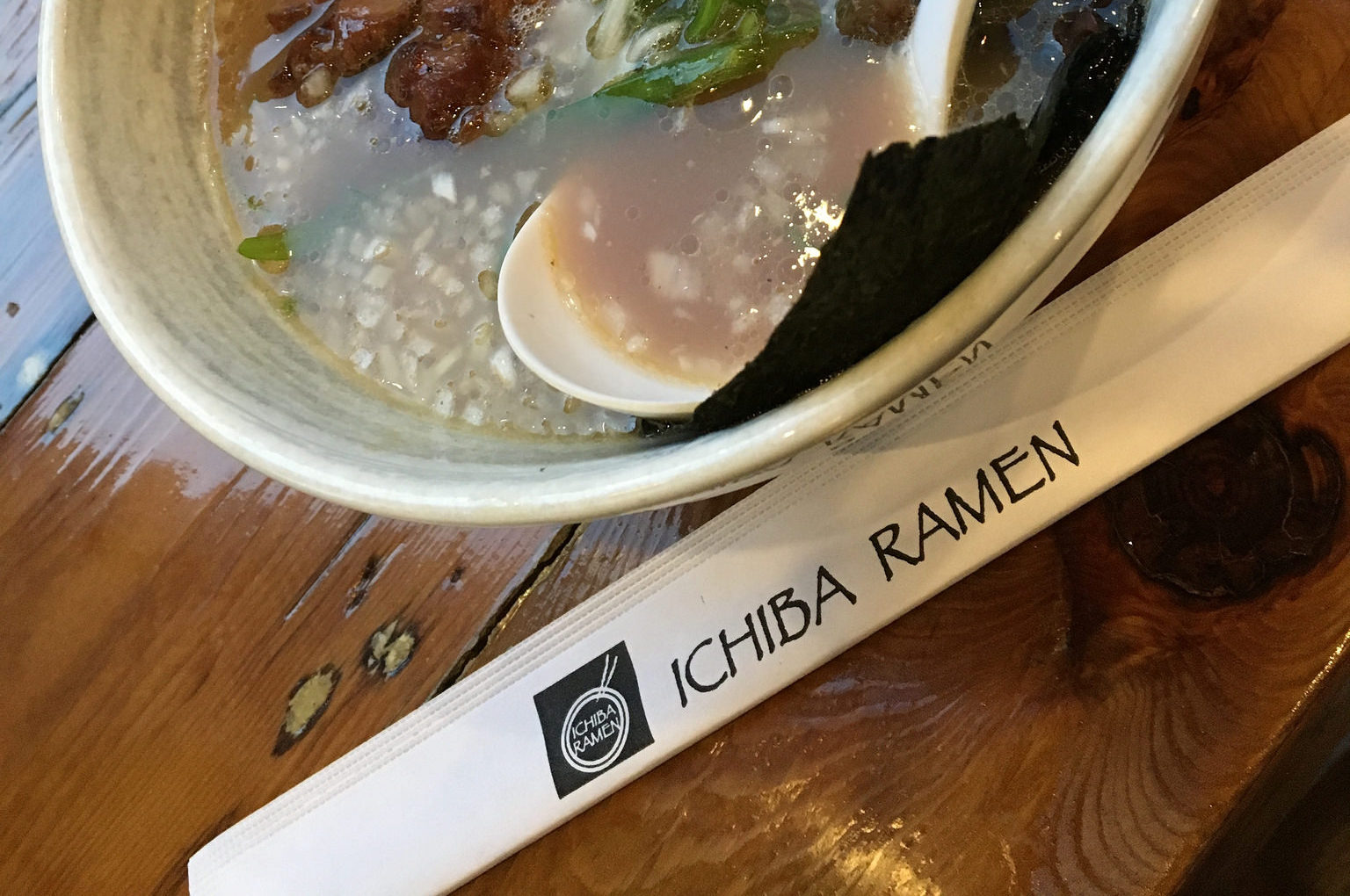

The trouble started last July, when the department’s civil rights division received a complaint from a job applicant alleging that Ichiba Ramen, a then-new ramen joint inspired by Tokyo’s Koreatown, wouldn’t hire him as a waiter because he wasn’t Japanese or Korean. After an investigation, the department found he was right. Ichiba had discriminated against him on the basis of national origin, it said, which is illegal under federal employment laws.

As a consequence, Ichiba will pay the job seeker $1,760, another $2,000 to the U.S. Treasury, and for a year, submit to periodic inquiries from DOJ to make sure it’s following the letter of the law. The settlement doesn’t say what will happen to the restaurant if the owners violate employment law again, either within the year covered under the settlement, or beyond, after the agreement expires.

Despite that law, and the potential illegality of ignoring it, the notion that the people serving your food should resemble the people who’ve historically made that food seems to endure, particularly in New York. Two years ago, for example, the city fined a kosher Indian restaurant $5,000 for seeking an “experienced Indian waiter or waitress” on Craigslist. Then there’s when keeping it real goes horribly wrong: Last year, one of New York’s most prominent sushi chefs, who is white, was fired for using a fake Japanese accent while serving customers.

But arguments of that kind haven’t held up in matters related to race, ethnicity, and nationality. As a government lawyer explained to Freakonomics, her office successfully sued a Mexican restaurant in Houston that had fired black and Vietnamese waitstaff because they couldn’t speak Spanish. The restaurant’s “diverse” clientele didn’t only speak Spanish, she said. Therefore, language skills weren’t a “business necessity.” Nor, presumably, were more subtle attributes of service work—like an appearance of authenticity.

Of course, there’s plenty of gray area. Many of us are used to eating in restaurants where employees seem to embody or visually represent the food that’s on the plate. Does that mean illegal discrimination actually occurred? Maybe job applicants are self-selecting. Maybe no one wants to take it upon themselves to complain, or knows who to complain to. And maybe the issue is just one of those icky things no one wants to talk about. Restaurants provide a kind of theatre, after all, and even if it’s unequal under the eyes of the law, there’s no fun in shattering the illusion.