Lela Nargi

As we rely more heavily on managed bees—largely for California’s $5.6-billion almond crop—wild bees are increasingly under threat.

The U.S. Geological Survey’s Native Bee Monitoring and Inventory Lab in Beltsville, Maryland, occupies a metal garage surrounded, on a recent “Queen Quest” afternoon, by November-brown fields. Inside, old wildlife books, antique taxidermy, and stereo microscopes are framed by a ribcage of stacked pizza boxes holding tens of thousands of pinned Hymenoptera specimens. They represent 20 years’ worth of work by wildlife biologist Sam Droege.

Droege runs both the Quest and the lab, the founding mission of which is at once specific and amorphous: “To develop survey programs for native bees”—like the Bombus, or bumblebee, queens he’ll be seeking this day—“so we could talk about whether they’re declining or not,” Droege said. Basically, we know bees are out there, some 4,000 species native to the U.S. alone. But we understand so very little about them and the ways they work within the ecosystems they inhabit. Droege’s lab exists to try to correct that.

Droege delivered scant instructions to a group of Questers armed with spades. These were best guesses about where in the ground to look for holes that Bombus queens dig to overwinter in: “Where the dirt’s loose, and there’s evidence they like to be in the shade,” maybe facing north, Droege said. He led the hunters out to a windbreak of hemlocks. Everyone dug fruitlessly between tree roots for a while. Then they moved over to some abandoned sheds that once housed a government breeding program for endangered whooping cranes. Dilapidated and overgrown with pokeweed, the sheds contained—no real surprise—no bumblebee queens. No Bombus fervidus looking like a lemony pompom. No Bombus impatiens with her velvet-black abdomen. An hour’s worth of toil ended where it began: with a persistence of not-knowing.

Wildlife biologist Sam Droege digging for queens

Lela Nargi

The plight of honeybees succumbing en masse to disease, mites, and the case-of-the-missing-pollinators known as Colony Collapse Disorder (CCD) has received heavy media coverage since 2006. And much has been made of the critical necessity of honeybees to our global food supply. But if you eat fruits and vegetables that you didn’t raise in your own little garden, chances are high that you’ve eaten something—greenhouse tomatoes or strawberries, orchard-grown apples or cherries, blueberries from Florida fields—that was pollinated by other kinds of commercially managed bees. These bees are raised in labs or collected from fields by “bee ranchers.” They report for farm duty in cardboard “hives” or in some cases still snoozing in their own cocoons, ready—or almost ready—to buzz off to work.

Agriculture in the U.S. employs almost 3 million honeybee colonies every year, largely for California’s $5.6-billion almond crop. But it’s begun relying ever more heavily on managed native bees—honeybees are transplants from Europe and elsewhere—as renting honeybee services becomes more expensive, as more crop production moves indoors, as we learn more about the ways pollination from multiple kinds of bees can lead to better yields. At issue, though, is the potential for these other species of managed bees to spread disease to wild bees, and the devastating impacts that might be having on our ecosystems.

“Queen Quest” hunters dig for Bombus queens beneath hemlock trees

Lela Nargi

Eleven miles southwest of Droege’s Queen Quest, at the University of Maryland’s (UMD) Honey Bee Lab, researchers reported that in 2018 and 2019, commercial honeybee colonies experienced their worst winter die-off, with a 38 percent loss. It’s just the sort of bad news that continues to fuel hopes for crop pollination salvation on managed non-honeybee species. But a not-knowing about where the balance lies between negative consequences for wild bees, and positive outcomes for farming, looms over the whole enterprise.

A brief history of managed bees

Using non-honeybee species in agriculture began after World War II, with (non-native) leafcutting bees. It was kind of an accident. Farmers raising alfalfa seed for livestock forage noticed that fields visited by these sleek, striped, solitary fliers had vastly higher yields than those pollinated by honeybees.

“The recognition that certain [bees] were better than others for certain crops led to the creation of the [USDA-ARS’s] Logan bee lab, where I used to work, bio-prospecting for pollinators,” says Jamie Strange, now chair of Ohio State University’s entomology department. The lab has raised Alfalfa leaf cutting bees. And also blue orchard bees—BOBs. These gentle insects, iridescent turquoise with blonde stubble, are useful in orchards because they fly in cold weather, when the trees flower. They also pollinate well in tandem with honeybees. “When you have a diversity of pollinators, you have better pollination,” says University of Florida entomologist Rachel Mallinger.

In 2007, Colony Collapse Disorder caused the price of honeybees for almond pollination to “shoot up,” says Steve Peterson. He raises BOBs at his Foothill Bee Ranch at the base of California’s Sierra Nevada Mountains. “That made it pretty clear that we needed to have alternatives.” Paige Embry, in her 2018 book Our Native Bees, highlights the fear that colony collapse stoked in the ag community, with one biologist asserting, “We are one poor weather event or… bee loss away from a pollinator disaster.”

“There was a big disease outbreak, then people started to notice certain species of wild bumblebee declining.”

Meanwhile, various researchers had succeeded in breeding some species of bumblebee. In the 1990s, Bombus occidentalis, the western bumblebee, made its way across the country to pollinate greenhouse tomatoes—a crop and growing situation honeybees deplore. But it didn’t remain tidily inside the greenhouses where it toiled. It meandered out to surrounding fields and forests and unwittingly wreaked havoc. On the West Coast, “There was a big disease outbreak, then people started to notice certain species of [wild] bumblebee declining,” says Strange. One was Franklin’s bumblebee. It hasn’t been seen since 2006 and is feared extinct. Despite only circumstantial evidence that Bombus occidentalis was culpable, Strange calls Franklin’s the number one casualty of commercial bumblebees and its disappearance, a “classic ecological catastrophe story.”

Bombus impatiens, the common eastern bumblebee, was cleared for use next, and remains the primary greenhouse pollinator in North America.

BOBs & Bumbles

According to Droege, “We’ve done a crappy job” of learning much of anything about Franklin’s and the 4,000-plus bees that are native to the U.S. We do know that most are solitary, living out their one year on Earth (most of it in hibernation-like diapause) alone. A lot of them nest underground, taking over animal burrows or tunneling in dirt. They often forage in just one or a handful of plants. The few we’ve domesticated are either social—bumble queens raise colonies of up to a few hundred offspring that fly for a single season. Or they’re aboveground nesters. Bee wranglers exploit these traits for commercialization.

Peterson, for example, puts out wood laminate boards that contain holes for wild BOBs to lay eggs in. He collects their nests. In fall, after the now-larval-stage bees have spun cocoons, he transfers these to a cooler until just before peak flower time. Then he distributes them to growers, who incubate them at room temperature before placing them in their fields. Two companies—Biobest (which did not respond to interview requests) and Koppert—breed bumbles in North America by imitating the bees’ natural cycle in heavily controlled rearing facilities; boxes containing about 50 workers are then sent to growers.

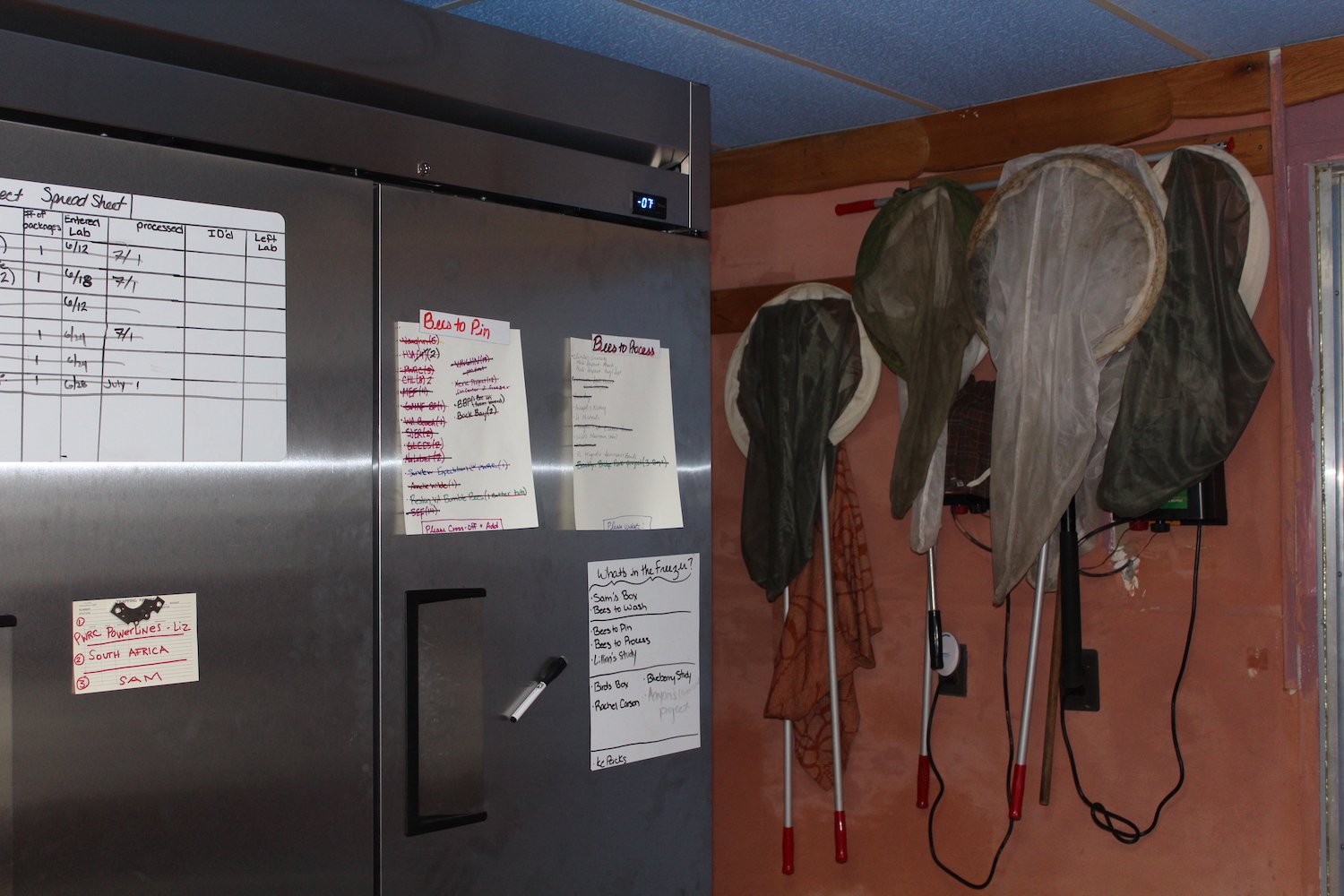

Collecting nets and a fridge full of bees waiting for processing

Lela Nargi

Here’s the problem: Different as managed bees, including honeybees, are from each other, they’re alike in that they outcompete wild bees for pollen and nectar. Diseases are also an issue. BOB larvae are susceptible to things like chalkbrood fungus; lab bumbles fed on honeybee pollen can contract an intestinal parasite called Crithidia bombi; honeybees are plagued with multiple fungi and viruses. As the cautionary Franklin’s story foretold, these bees can go on to infect wild bees.

Have lessons been learned—and implemented—since the early, pathogen-laden days of Bombus rearing? Peterson subjects his BOB boards to rigorous cleaning to ward off disease and only sells bees locally, to keep from genetically mixing species, which can cause mismatches between bee hatching and flower blooming times. It’s impossible to know if other bee managers are equally conscientious.

Lab-reared bumbles can contract viruses from honeybee-collected pollen that’s brought in to feed them. Companies might gamma irradiate pollen to sterilize it. Belgium-based Koppert, which raises American-market bumbles in Michigan, asserts in a press release that it uses a “pure culture isolation” technique to eliminate pathogens, and undergoes disease audits from staff, government inspectors, and university-affiliated entomologists. But “the jury is out” as to whether U.S.-raised bumbles are disease-free, says Strange, while owning that companies have “incentives to raise healthy bees.”

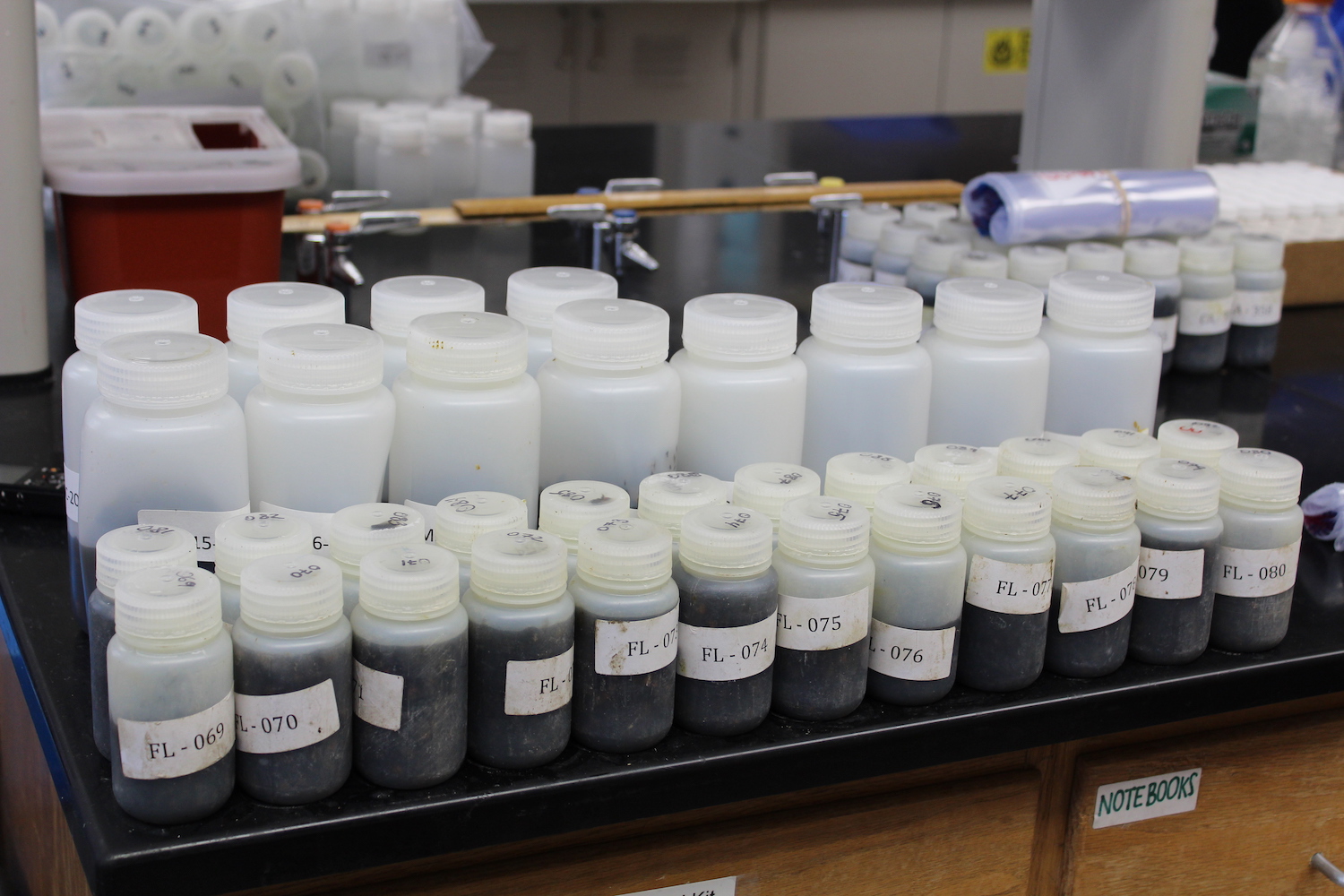

Samples of honeybees awaiting processing and disease ID at the University of Maryland’s Honey Bee Lab

Lela Nargi

Researchers are currently trying to breed western bumble species to replace Bombus impatiens, which is used, widely, outside its range; only Oregon prohibits its importation. Some argue that regulations need to be more stringent: “Beyond Oregon, regulatory oversight is not really there and legislative action has never been taken to fix any of this,” Strange says. Meanwhile, in Chile, Argentina, Japan, New Zealand, which have followed U.S. Bombus mistakes, collapse of native species is underway.

The status of wild bees

A recent article in the International Journal for Parasitology calls for, among other improvements to the system, encouraging growers to plant wildflower strips and cut down on mowing. This would ostensibly attract more wild bees and help reduce agricultural reliance on managed bees.

“If we can provide more healthy, uncontaminated habitat to augment native bees, that would go a long way to help pollination services.”

New research supports this latter recommendation, which maintains that crop pollination has barely suffered with honeybee collapses. The reason? Wild bees have filled the gap. “Every time we look, native species pollination is higher than we think,” says Tara Cornelisse, senior scientist at the Center for Biological Diversity’s Endangered Species Program. “If we can provide more healthy, uncontaminated habitat to augment native bees, that would go a long way to help pollination services,” she says.

There’s a catch. Mallinger points out that the usefulness of native bees depends on what crop you’re growing and where. A small orchard or crop farm in New York “may support diverse pollinator communities. I could see the argument for reducing reliance on domesticated bees there,” she says. (The other catch: yield-reliant farmers are trepidatious about dropping managed bees altogether.) But Mallinger works with Florida blueberries—a monoculture like California’s almonds—which bloom before native bees are out, in landscapes that have been depauperated of diversity. Wild bees aren’t an option here, or in greenhouses.

“There are reasons to commercialize [native bees] in the intensive-agricultural world we’re moving toward, to have some alternatives” to honeybees, says Strange. But “Where do we draw line as to what’s the right amount? That’s a broad philosophical question. The evidence is that we won’t wipe everything out, but also that we will wipe some things out. It’s happened in past; not to expect it in the future would be foolish.”

As UMD’s Honey Bee Lab awaits data collection this coming April that will show how honeybees fared in 2019 and into 2020, widespread not-knowing about native bees continues. “On the positive side, probably everything is still out there somewhere,” Droege says. “On the negative side, we still know so little. If anyone tells you they know the status of native bees, they don’t.”