Everybody’s heard the unsettling bit about the razorblade-spiked Halloween apple. But for three decades, Joel Best, a sociologist at the University of Delaware, has been a calm, consistent voice of reason: No, the neighborhood evildoer isn’t going to tamper with the local trick-or-treaters’ candy.

In a paper he’s updated every year since 1985, Best has tried to puncture the myth of what he calls “Halloween sadism”—a term adapted from a freaked out 1974 op-ed in PTA Monthly about the dangers of the season. Though Best has found many reports of children supposedly injured, sickened, or killed by Halloween candy, further scrutiny typically reveals these incidents to be apocryphal, accidental, or a hoax perpetrated by the kids themselves. In his 30 years of studying the topic, tracking down reports from the 1950s on, Best has never found a single “substantiated report of a child being killed or seriously injured by a contaminated treat picked up in the course of trick-or-treating.” The whole thing is basically an urban myth.

Shyne was one bad apple, but the incident seemed to stoke the nation’s fears. In October, 1970, The New York Times ran a sensational, unsubstantiated report claiming that:

“[The] plump red apple that Junior gets from a kindly old woman down the block … may have a razor blade hidden inside. The chocolate ‘candy’ bar may be a laxative, the bubble gum may be sprinkled with lye, the pop corn balls may be coated with camphor, the candy may turn out to be packets containing sleeping pills,” among other horrors. The reported cited a warning from New York State’s Health Commissioner claiming “pins, razor blades, slivers of glass and poison” had “appeared” in treats gathered by the state’s children.

According to Best, such dangers are the unproven stuff of legend. And yet the fear of tainted candy persists even today. So the question remains: if Halloween sadism isn’t really happening, why is everyone so scared of it? Why do we keep repeating the same story about a razor hidden in an apple?

The practice of trick-or-treating became common as a kind of friendly extortion: If plied with treats, children might be willing to forgo their tricks.

It’s partly a story about community, how the breakdown of the American social fabric led to fears the folks next door might poison your kids. But it’s also a story about food. Because Halloween, like most holidays, centers around eating—and the delight and anxiety surrounding it reveals a lot about our changing relationship to food.

In the early 20th century, the worry wasn’t tainted Halloween goodies. It was that the local kids would take their pranks too far. The holiday was primarily a night of mischief, and the threat of cheeky vandals kept everyone on guard. In his 1959 essay “Halloween and the Mass Child,” the sociologist Gregory P. Stone looked back on the Halloweens of his 1930s childhood, long nights of labor-intensive devilry; one year, for example, Stone and his crew dismantled someone’s front steps, took down his rain gutters, threw the eaves onto the porch with a terrible clatter, and hoped that in the resulting chase their startled neighbor would careen off the stepless porch and into the evening air.

Sweets of any kind—let alone great hoards of packaged, mass-produced candy—simply weren’t a part of it.

“It was long, hard, and careful work,” Stone wrote. “We had no conception of being treated by our victims, incidentally, to anything except silence…irate words, a chase (if we were lucky), or, if we were lucky, an investigation of the scene by the police.”

The practice of trick-or-treating became common as a kind of friendly extortion: If plied with treats, children might be willing to forgo their tricks. “The practice is ostensibly a vast bribe exacted by the younger generation upon the older generation,” Stone wrote, a “payoff in candy, cookies, or coin for another year’s respite from the antisocial incursions of the children.”

Stone argued that he saw this shift occur in his lifetime, viewed through the lens of changing Halloween traditions. The creative, work-intensive pranks of his childhood were replaced instead by a ritual of performed consumption: On Halloween night, the neighborhood becomes a mall, and the kids methodically stock up. Their plastic pumpkin loot buckets might as well be shopping bags.

But you can also see that shift from production to consumption in the treats themselves—and that’s where this becomes explicitly about food. Even in the 1950s, pre-packaged candy was not yet the good of choice. Stone describes the spoils of his day as “candy, cookies, or coin”—pre-packaged candy was just another favor, along with baked goods and currency, that trick-or-treaters could expect to find. (Coins were so common that they featured in another apocryphal story about Halloween sadism, one mentioned in the 1970 Times article—cruel neighbors would heat their pennies with an iron and press them into outstretched, unsuspecting hands.) By now, of course, we know that candy reigns supreme, that the holiday has become basically synonymous with confectionary brands like Mars, Nestle, and Reese’s. And that, as you might guess, was not by accident.

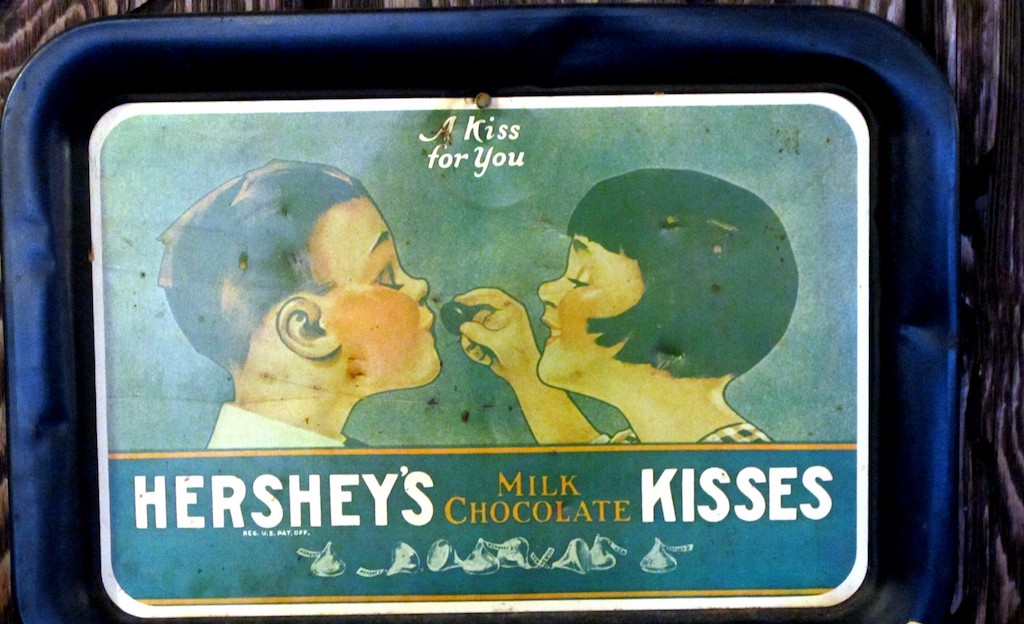

Candy companies obviously caught on that Halloween had become a day that boosted sales. And in the 1950s and 60s, looking for ways to increase the trend, they spent heavily on ads that linked their products to All Hallows Eve. (There is a great list here.) “You mean I can have some of each?”, a pirate-costumed tyke asks a neighbor, as she holds out a tray stocked with the company’s branded lollipops, mints, and candy corn. “Be good to your goblins,” recommends another, with an archeyptal fifties housewife offering king-sized Baby Ruths and Butterfingers to a costumed duo. “Tricks or treats are lots more fun than chasing little spooks away from the front gate,” according to the copy in an ad for Mars’ Milky Way bars. “Here’s the trick that keeps ‘em on good spookin’ terms…. Buy ‘em by the box for ‘Tricks or Treats.’”

Halloween has always been about what scares us. And what scares us today, apparently, is food that lacks some kind of corporate seal.

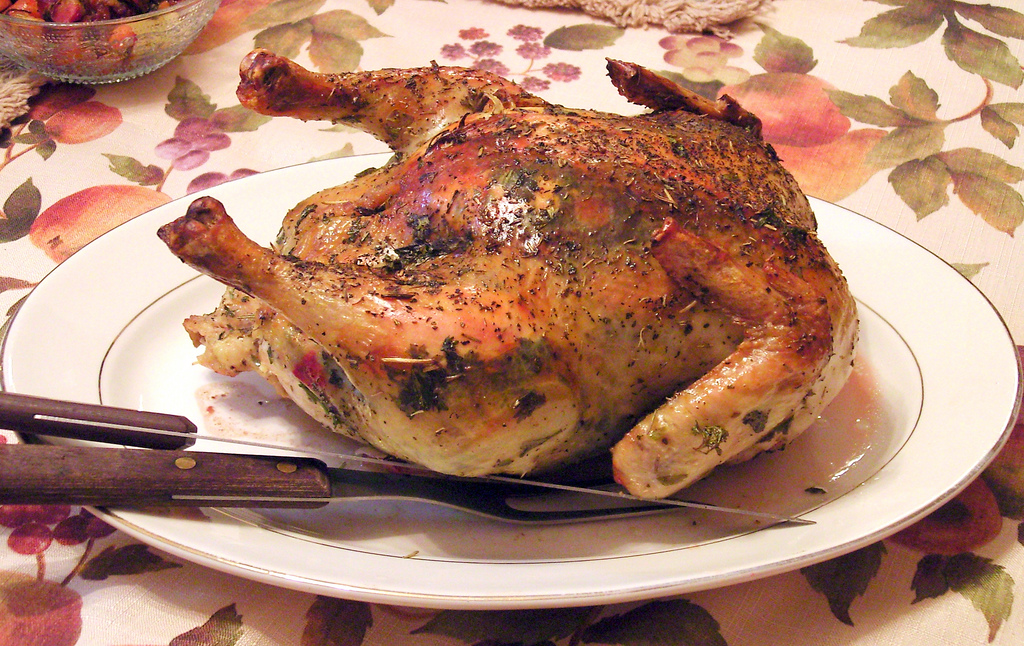

Which brings back to the razorblade in the apple. Because as advertisers successfully made mass-produced candy the treat of choice, other types of goodies—the homemade kind—started to seem more sinister. It’s telling that the archetypal act of Halloween sadism features a cutting edge tucked an innocuous piece of fruit.

There’s no reason to believe that the candy industry helped stoke these fears in any direct way—though doing so would have been a Don Draper-like stroke of genius—and may be reason to believe the opposite. Best tells me that, in 1986, the year after he published his now-famous article, the National Confectioners Association, the trade group representing candymakers, paid him to field journalists’ questions on the topic. They didn’t tell him what to say, but they wanted to be sure he was out there talking to the press, pointing out that the latest rumor about tainted treats is probably just another scary story. Best’s impression is that candymakers hate the myth of Halloween sadism, and want it to go away.

How much of that is a result of efforts by candymakers? It’s hard to say. It’s probably not surprising that, on its website, the National Confectioners Association provides a list of Halloween safety tips, one that encourages us to “only give and accept wrapped or packaged candy.” What’s more surprising is this: NCA’s candy-related directives have been reprinted—verbatim—by police departments and city governments from Cleveland, Ohio to University Park, Texas. Some cities—like Edwardsville, Illinois—reprint the entire list word for word, down to a bit about pets being frightened by children in masks. I contacted NCA to determine whether the association makes safety-related Halloween outreach to municipalities and local police departments, but had not received a response by press time.

Halloween has always been about what scares us. And what scares us today, apparently, is food that lacks some kind of corporate seal. Familiar brands—Mars and Nestle, Cadbury and Brach’s—somehow reassure us that a product is not just quality, but basically safe. Meanwhile, foods that lack their well-known insignias don’t carry that guarantee—and that’s where the anxiety starts to sneak in.

This shift is bigger than Halloween. The same fears persist about schoolyard bake sales, for instance, now largely replaced with fundraisers featuring mass-made, pre-packaged treats like Girl Scout Cookies. Meanwhile, so-called “cottage food” laws—which allow citizens to sell their home-baked and farm-raised goods, neighbor to neighbor without government oversight—continue to cause discomfort. In Maine, a new “food sovereignty” law, the state’s effort to allow its citizens more latitude the sale of small-batch food made in unregulated kitchens, has been challenged by the federal government. From the steps of Halloween porches to the highest reaches of the FDA, we’re simply more comfortable with food that’s been produced in gleaming, state-inspected commercial facilities.

Marcel Oosterwijk

Marcel Oosterwijk The real, demonstrable hazards of Halloween are the ones we tend to ignore.

Like many compelling fears, this anxiety has an element of irrationality. Best’s ongoing research hasn’t uncovered any examples of Halloween deaths by food poisoning. By and large, people are probably going to be extra careful with whatever they hand out to dozens of local kids—after all, their parents know where you live. Not that Halloween isn’t dangerous—just that its real, demonstrable hazards, the ones related to traffic safety, are the ones we tend to ignore. Halloween is the most deadly night of the year for child pedestrians. But we’ve accepted the automobile into our lives, and the peril that come with it. Not so much, apparently, the risks of unpackaged, under-regulated food.

Which brings up a final irony. What kids do gorge on, each Halloween, isn’t great for them. There’s an epidemic of diabetes in this country, one projected to affect 40 percent of American adults in their lifetime, and one in two people of color. And yet, we’ve been content to sit by while a national holiday—one with ancient roots in pagan rituals, 2,000 years ago—has become, essentially, a celebration devoted to the purchase of corporate sweets, the consumption of high fructose corn syrup. In trying to defend ourselves against imagined bogeymen, in other words, we’ve let another danger come to stay—one that’s much more subtle, but also much more real. Maybe that’s what’s really scary, in the end: our ability to fool ourselves, our inability to tell which dangers really matter, the fickle nature of our fear.