Zak Grade

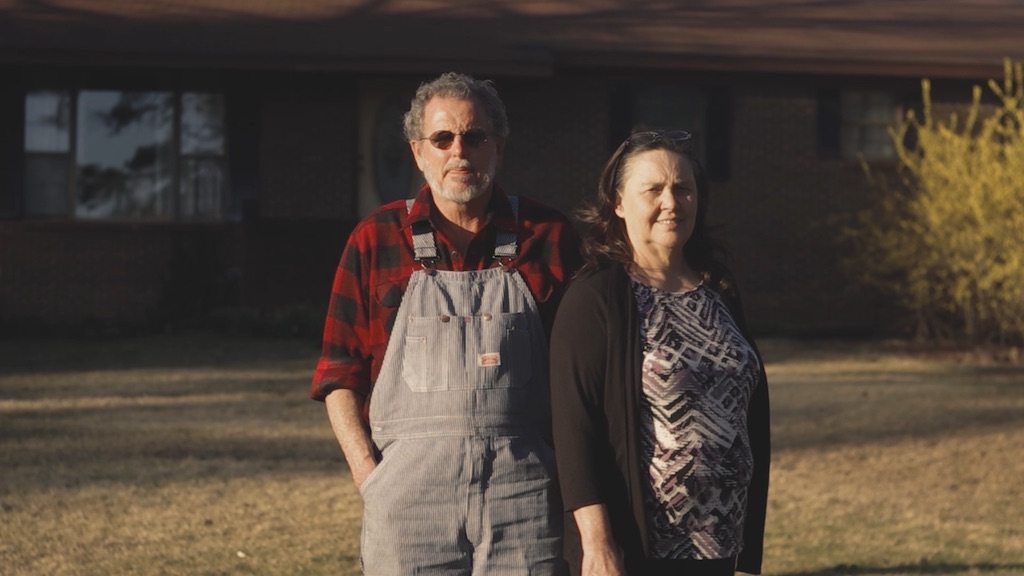

In 1987, Karen and Mitchell Crutchfield started growing chickens for Tyson Foods. It took a lot of money to get up and running: about $150,000 to build two chicken houses on their property in Lamar, Arkansas. But, as it turned out, the initial costs were only the beginning. Right away, the couple says, Tyson began requiring costly adjustments. Before it would even make the first shipment of birds, Karen says, the company wanted improvements to the road leading to the houses. Later, it made them change over from water troughs to nipple feeders. Then, it wanted a newfangled freezer system to store dead birds until they could be picked up for composting.

The upgrades seemed never to stop. Some were comparatively small—$10,000 here, $20,000 there—but they added up. As the couple increased production by building four more houses between 1990 and 2000 (an investment that left them with several hundred thousand dollars in 15-year loans), they estimate that Tyson also requested an additional $150,000 worth of mandatory upgrades. “They just had something all the time that they wanted you to put in new,” says Karen.

Debt made things hard. For every paycheck, the Crutchfields took home only half of what they earned. Tyson sent the other half directly to Farm Credit, the Crutchfield’s lender. Karen took off-farm jobs to help make ends meet, but it wasn’t enough. They sold stock to keep going, including every one of the 3,000 Tyson shares they’d bought. Then they cashed in Mitchell’s 401k. They cut timber from their property and sold it; eventually, they took on equity in the land itself. By 2010, after more than twenty years of hard work, they were almost out of the hole, only about three years away from being free and clear of farm debt, and hoping, for the first time, to actually make some money.

“There was light at the end of the tunnel,” Mitchell says.

Marcello Cappellazzi

Marcello Cappellazzi Karen and Mitchell Crutchfield were nearly out of debt when Tyson asked for a quarter-million dollar upgrade

Then Tyson came around with another required upgrade.

This time, the couple says, the company wanted digital infrastructure: a state-of-the-art computer system that would help automate water flow, heat, and other parameters inside the barns. The upgrade might have brought along some environmental benefits and utilities savings. But the estimated cost? Between $250,000 and $300,000.

At his age, Mitchell says, it made no sense to take on that kind of obligation.

“We couldn’t see taking on another 15 years. There just wasn’t no way,” he says. “I would have been at least 75 years old. You don’t know what your health is going to be. The older you get, the more you got to take care of. It’s just not age-friendly to take on debt like that when you’ve got to do all the labor yourself.”

And yet they applied for the loan anyway. They didn’t have a choice, since they were still in debt, and had no other way to make the money back. Karen had a plan: if they updated only the four newest houses, letting the two 1987 originals lapse into obsolescence, they might be able to pull it off. But things didn’t work out when she approached Farm Credit for the ask.

“At first, they told me that I had it. But when they found out I was only going to do four houses, then it came back that I wasn’t going to get my money,” she says. “Tyson and Farm Credit have a meeting every month to discuss their growers and what they’re going to do with them. So if Tyson needs six houses in production, Tyson’s going to get six houses in production.”

The Crutchfields didn’t put in the computer system. And Tyson stopped delivering new chickens, effectively shutting down the farm. And the couple took the last option they had left: filing for Chapter 12 bankruptcy.

Marcello Cappellazzi

Marcello Cappellazzi Broiler chickens are raised indoors, and farmers are responsible for the cost of construction. Above, Craig Watts, a poultry industry whistleblower and a plaintiff in the case

And the fact that it happens in the poultry industry is not exactly news. (One recent and relatively mainstream portrait: the debt-burdened chicken farmer in the 2008 film Food, Inc.) What is new is the possibility that big companies may conspire to make such exploitative relationships easier to achieve and maintain.

Last Friday, a group of law firms filed a class action lawsuit in the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Oklahoma alleging that five of the country’s largest poultry companies—Tyson, Perdue, Pilgrims Pride, Sanderson Farms, and Koch Foods—have colluded for years to keep farmers in debt and underpaid. We’ve reported on a similar suit filed in September, which claimed that the same companies, plus about a dozen others, used Agri Stats, a private data clearinghouse, to share trade information and thus manipulate the price of chicken. That suit was on behalf of chicken buyers, though. The Oklahoma suit focuses on the other end of the supply chain, claiming that the same collusion also led to lower prices for farmers.

According to the suit, the defendants—referred to as “integrators” because they own entire supply chains, from the grain mills to the slaughterhouses to the birds themselves—work together to create an environment that forces farmers to contract with one and only one parent company. (Economists have a fancy term for this: “monopsony,” a market with only one buyer.) Growers say that arrangement leaves them vulnerable, because without other options—sell to Perdue, say, or sell nothing at all—there’s no way to command a fair market price.

That, the plaintiffs say, is just the way the integrators want it. “Since at least 2008, and likely much earlier,” they write in the filing, “Defendants and their Co-Conspirators have agreed to and have shared with themselves (but not with Growers) detailed Grower compensation information, with the purpose and effect of suppressing Grower compensation. This agreement has been bolstered by a parallel agreement among Defendants and their Co-Conspirators not to solicit, hire, or ‘poach’ one another’s Growers.”

Or, as one farmer quoted in the filing puts it: “After a few months into the business I realized that the integrators have an unwritten pact with their sister integrators, “You don’t take our growers and we won’t take yours.”

Tyson, for its part, denies the allegations.

“We want our contract farmers to succeed and don’t consult competitors about how our farmers are paid. These are false claims,” Gary Mickelson, Tyson’s senior director of public relations, told New Food Economy, in an email. “The farmers are free to discuss the terms of their contracts with whomever they want, including other farmers, and are also free to switch to other chicken processors who operate in their area.”

But the suit also spells out another detrimental practice: the way poultry companies extract farmer loyalty by demanding expensive building and equipment upgrades, trapping them in a cycle of debt. That also has an anti-competitive effect, whether there was collusion or not.

Expensive, unending, mandatory upgrades may really be about evolving technology and increased efficiency. But they also tend to make farmers completely reliant on one single company. Think of it like an iPhone from hell: you have to make every single update Apple puts out, or the apps stop working. Except in this case, the mandatory updates can cost north of $200,000, and you depend on the apps for your livelihood, and you’ve mortgaged your home to pay for the phone.

According to the suit, that’s by design. “Integrators often monitor Growers’ debt burdens, requiring them to undertake unnecessary and expensive upgrades if they ever do near financial independence—with the intent of keeping Growers debt-laden and subservient to a specific Integrator,” the suit claims. “The increased dependence on their Integrator forces Growers to accept any CFA [Contract Farming Arrangement] amendments and paltry pay offered by the Integrator or risk CFA termination (or nondelivery of flocks, a functional equivalent) and financial disaster.”

Though integrators do ask farmers to take the financial hit on upgrades they need to stay competitive, they do assume other costs that help the farmer. Integrators pay for the birds, for instance, as well as their feed—so farmers don’t get squeezed when corn prices spike. (Contract farmers also don’t benefit when they drop.) But small and mid-size chicken growers tend to carry the most debt, compared to their assets, in all of agriculture—which is compounded by the fact that their biggest investment, the chicken houses, are often useless to other companies. A Tyson house isn’t like a Perdue House, which isn’t like a Sanderson Farms house. Each company uses a unique, specific set of technical specs and proprietary equipment, and farmers who aren’t up to date will stop getting chicken shipments. This puts farmers in a bad spot: they’ve spent a fortune on chicken houses that, other than growing birds for one specific company, have no worth.

And that’s where the allegations come in. Because there’s probably no real reason a modern chicken house couldn’t grow chickens for one company and then another.

And that’s where the allegations come in. Because there’s probably no real reason a modern chicken house couldn’t grow chickens for one company and then another.“The barrier to transitioning to another integrator, even if they’re willing to take you, is often just the incredible expense and added risk that you take on to your business in making the upgrades,” says Sally Lee, program director of contract agriculture reform at Rural Advancement Foundation International (RAFI-USA), a non-profit that advocates for farmers in the south. “It could be that their house is a couple feet longer than the company you were working with. Or they have different feeders, or different requirements for water lines.”

Or, as Karen Crutchfield puts it, the differences are “nothing you really would need to grow a chicken.”

The fact that a house is three feet longer or shorter, or uses a different brand of water system, shouldn’t really be a deal-breaker. But these companies already control most of a heavily consolidated market, so they can make such demands—and a gentleman’s agreement between heavyweights would make it even easier to keep farmers from looking for a better deal.

Still, the question remains: why would poultry companies want their producers to struggle? Wouldn’t they want to reward their good work, and not bury them in debt as the suit alleges?

That’s the case Tyson makes. The first words of Mickelson’s statement say, “we want our farmers to succeed,” and the company’s website claims that it does not require producers to make upgrades: “Each farmer must decide on their own how much debt they’re willing to take on,” it says. “We don’t make such decisions for them. However, we do provide financial incentives—more pay—to farmers who decide to upgrade to premium housing.” Integrators also aren’t just asking farmers to take the hit—

So I asked Mitchell whether he thought it’s true that Tyson wanted to keep him in debt, and if so, why.

Sure they did, he says. “Once [farmers] get out of debt, they can say, ‘look, I’m not making no money, I’m going to shut my doors. If you want to come back with the pay, come back and talk to me, and we’ll grow chickens,’” he says. “But if you’re in debt, and you’ve got your home and all your stuff tied up with it, you can’t do that. As long as they can keep you making payments, and in that debt cycle, they can basically pull you into anything.”

In his view, debt is wielded as a source of power: it traps farmers in a system that they would otherwise flee if they had free choice.

Karen tells me Tyson gave only one raise in the last ten years they worked: a quarter of a penny per pound of chicken. “And can you imagine how much everything else has went up?” she says.

It wasn’t good enough. But once they’d started, they didn’t see a way out.

Marcello Cappellazzi

Marcello Cappellazzi Poultry growers contribute millions of dollars to rural economies

RAFI-USA’s Sally Lee says that poultry growers contribute much value to rural economies, even if they’re buried in debt, and even if they’re typically overlooked. After all, they collectively spend millions to build the barns that sustain the entire chicken industry—a significant investment that she feels current practices devalue.

“We have to remember that these are our rural investors. They’re putting up on average a million dollars or more to put up these chicken houses. This is an important link in the backbone of our American economy if we think about rural economies,” she says. “The fact that we have all of these farmers making a low or negative return on that investment, that’s a red flag.”

Lee is heartened by the new class action suits, though she admits that other suits that seemed promising at first were ultimately unsuccessful. That’s partly why RAFI-USA’s latest effort is to make an appeal to the general public: a documentary that highlights the economic plight of the nation’s of chicken farmers. The film, Under Contract, premieres in New York Wednesday, and will be available on Vimeo On Demand Thursday.

Maybe broader awareness will help reform gain steam. But relief may not come soon enough for farmers like the Crutchfields, who are featured in the film. They’re out of business, but still making payments on their debt. Their last hope is the lawsuit they’ve filed against their old employer, suing Tyson for lost pay due to a terminated contract (the technical term is “promissory estoppal”). No lawyer would take the case, so they’re representing themselves in court—a long-shot effort. The case was initially dismissed, but is currently on appeal.

A successful court ruling would be a victory, but time is running out.

“We’ve just been hanging on, keeping our payments going, and hoping we can get some kind of settlement going out of Tyson in court. We’re going to have to liquidate some of our stuff,” Mitchell says.

“We’ve got maybe a year,” Karen says, “or a year and a half.”