Last summer and fall, citizen-scientists in orange vests descended on waterways across southern Minnesota. They gathered water samples in stainless steel buckets from the Cedar River and its tributaries, smeared them onto petri dishes coated with growth medium, and heated them in incubators stashed in their garages. Forty-eight hours later, the petri dishes would reveal crucial details about the health of the waterways the samples were drawn from: Blue splotches emerged from the clear water to indicate the presence of E. coli, a bacteria that lives in the intestines of livestock but can be highly pathogenic in people. One splotch meant a healthy waterway; more than one would surpass the threshold considered safe for swimming.

All told, 40 volunteers collected nearly 500 samples from 83 sites across the Cedar River watershed, which starts in Dodge County, Minnesota and feeds into the city of Austin. And 70 percent of those samples contained more E. coli than is considered healthy for bodies of water in which people swim and play.

In a packed hearing in Austin last week, community members asked the Mower County Board of Commissioners to ramp up enforcement of water quality standards. “Our grandchildren, they can’t help but be drawn to the creek,” resident Nancy Dolphin said in tears, according to the Minneapolis Star Tribune. “But the water that flows by our house is not safe for them. I’m a grandma. What do I do?”

At that meeting, the commissioners agreed to look at ways to encourage homeowners with outdated septic tanks to upgrade their systems. Don Arnosti, state conservation director for the Izaak Walton League, a national environmental organization, and the organizer of the E. coli testing, says an estimated 1,700 homes in Mower County may be leaking waste into the water.

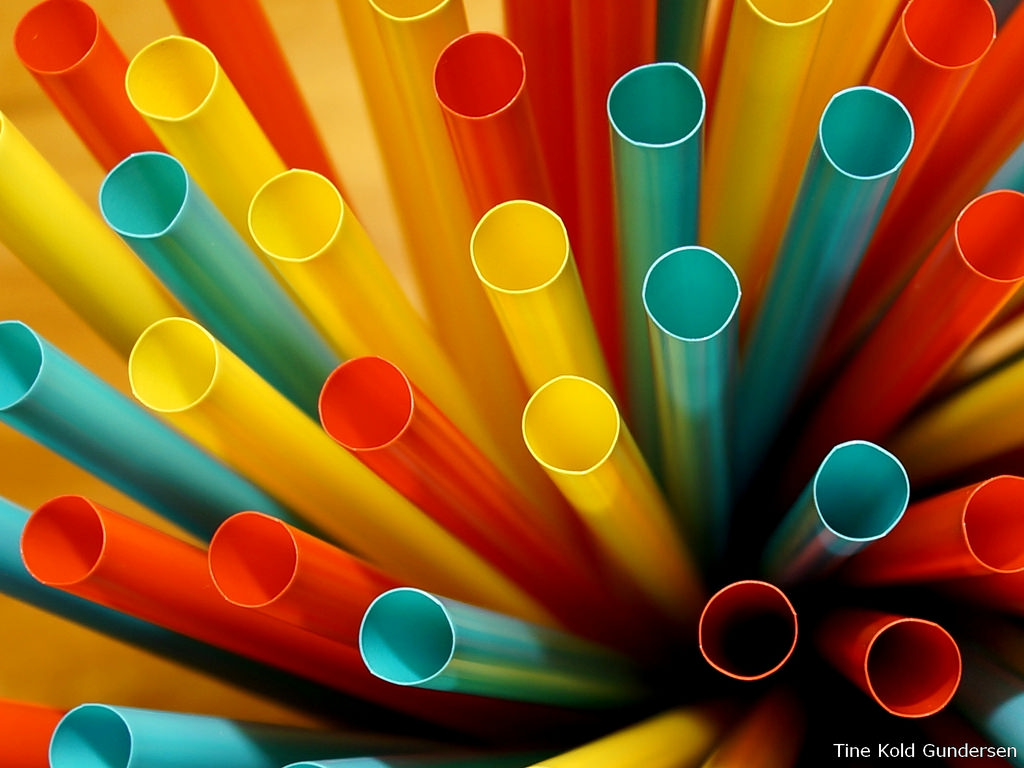

40 volunteers collected nearly 500 samples from 83 sites across the Cedar River watershed. The samples were then spread onto petri dishes, like the ones photographed here, which can indicate the presence of E. coli

But human waste is only one part of the equation. DNA samples from the testing sites revealed that the E. coli found in the river also came from cows and pigs. The area surrounding the Cedar River watershed is home to a few small pastured cow operations and several large-scale hog farms, most of which sell to the Hormel Foods plant in Austin. Arnosti says the DNA samples did not indicate how much of the waste comes from the pig farms compared to the cows and the septic tanks. But consider this: As of 2017, nearby Dodge County was home to 237 feedlots—in a total area of 440 square miles.

That’s why Arnosti is hoping to involve Hormel in water quality improvement efforts. As the buyer of many of the hogs being produced in the area, the company has the power to hold its producers to a higher standard. Hog manure is typically sprayed onto fields, and Arnosti says the highest E. coli levels were evident after big storms. That could mean the manure is running off the fields and into the water. According to Hormel, 90 percent of its producers’ manure is sprayed according to best management practices.

Arnosti says he’s asked Hormel to co-sponsor a workshop on practices that restore soil health and to be proactive in building a greener supply chain. So far, the company hasn’t committed to anything. “We’ve had pleasant murmurings from them, but we have not heard a substantive yes to any of our requests,” he says.

The hold-up, of course, is money. Updating a home septic system costs more than keeping an old one—and county commissioners are loathe to ask their constituents to spend hard-earned dollars making updates to systems they can’t even see. And if Hormel wanted its producers to be more careful when disposing of thousands of gallons of waste, it might have to pay them enough money to make that change economically feasible. (Or not, but if it imposed a lot of new rules and didn’t raise prices, the company would have a lot of angry hog farmers on its hands.)

Still, Arnosti says he’s hopeful the high-level interest among community members in improving the watershed will make a difference at the county level. He says he thinks organized and engaged citizens are key to holding regulators and companies accountable.

New Food Economy

New Food Economy Wisconsin’s dairy farmers, much like Minnesota’s pork farmers, face an impossible decision: Respond to pressure to expand or resist expansion and potentially lose the farm

Three hundred miles east in Kewaunee, Wisconsin, Lynn and Nancy Utesch have been down this road before. Their county is home to several large-scale dairy farms, and they say cattle operations have caused issues similar to those surfacing in Minnesota.

The couple founded Kewaunee Citizens Advocating Responsible Environmental Stewardship (CARES) in 2011, then started testing their water in 2012 and continued until 2015. They funded the whole project with the help of friends, and Nancy estimates they spent at least $3,000 a year on the tests. “Our wage scales here are not that high,” Lynn adds. “If you made $30,000 in Kewaunee county, you’re doing good.”

Nancy says E. coli in the water has sickened Kewaunee children twice before: Once in 2004, when an infant bathed in well water that had been contaminated, and again in 2014 when a baby drank formula that had been mixed with tainted tap water. I wrote about Kewaunee County in 2017 when a nearby confined cattle operation was fined $50,000 for polluting its neighbors’ well water. Around the same time, Lynn Utesch, who is a U.S. Navy veteran, delivered a statement to the House Subcommittee on the Environment and Commerce, in which he said, “For over 13 years now, our community has had at least one infant admitted to the ICU poisoned with E. Coli, entire families including the family dog becoming poisoned after manure applications, and longtime residents moving to the city just so they can have clean water for their children.”

The biggest manure pit in Kewaunee County can hold as much as 76 million gallons of cattle waste, equivalent in size to several football fields. To make matters worse, the region is covered in thin soil and limestone and is prone to sinkholes and small streams which develop out of nowhere and run into the groundwater. “We have reached a tipping point where there is total recognition that what we are doing is poisoning the people here. It’s poisoning our aquifers. It’s poisoning the great lake here at Lake Michigan.”

Yet the Utesch’s cries for watershed improvement have largely fallen on deaf ears. Their county continues to allow farms to add new animals, even as advocates insist the surrounding land and water can’t absorb more waste. “I think at the end of the day we have regulations, but they’re not followed through with oversight and enforcement,” Nancy says.

Wisconsin’s dairy farmers, much like Minnesota’s pork farmers, face an impossible decision: Respond to pressure to expand, a decision which can lead to environmental degradation and angry neighbors—not to mention public health issues—or resist expansion and potentially lose the farm. Overproduction makes cheap milk and happy industry leaders, but it means low prices and environmental externalities for farmers and their neighbors.

As Goodman said in his op-ed, he learned in April that his milk buyer would no longer purchase his product. The information was delivered in a letter, also sent to 75 other Wisconsin farmers, and with that, his income had been yanked out from under him. He sums up the system’s externalities: “Farmers have been duped into producing too much milk. Their profitability is gone and as they are suffering, so is the quality of Wisconsin’s environment.”