“Therapy could stop superbugs on farms,” reads the BBC headline, which unfortunately does not continue on to a story about furnishing British pig pens with couches and expert listeners. The “therapy” in question is phage therapy, a treatment that shows promise as an alternative to antibiotic use in livestock and, eventually, people.

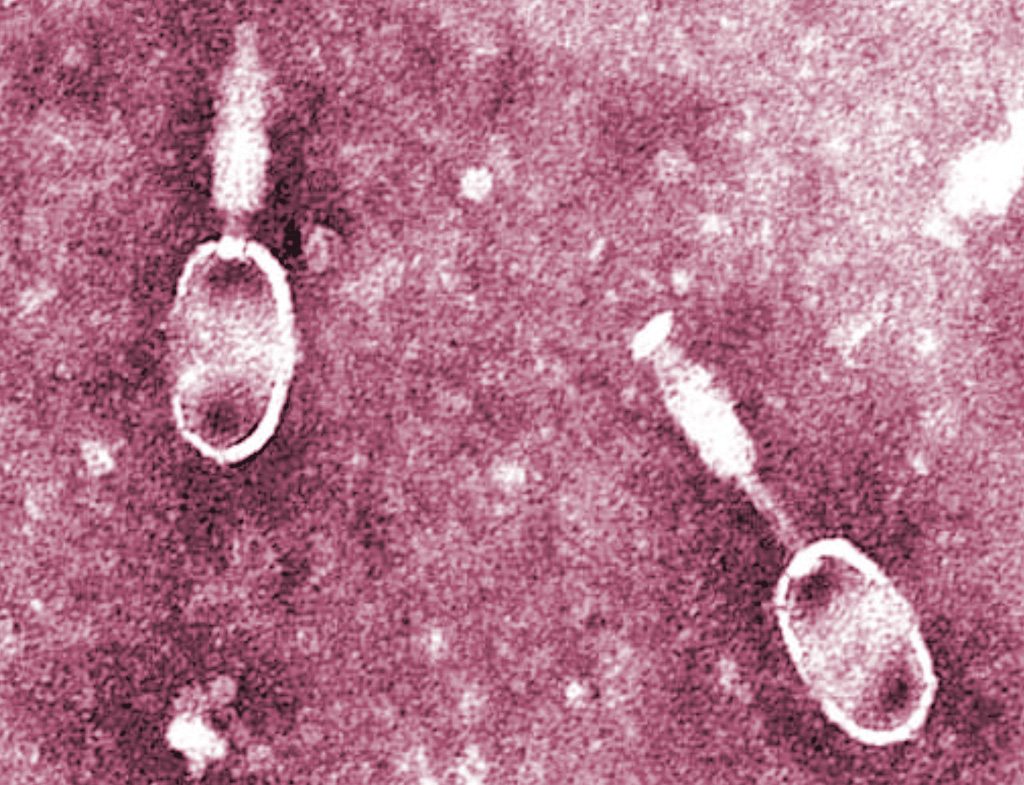

Phage therapy uses viruses called bacteriophages to infect specific bacteria (salmonella, for instance), a process BBC likens to a “guided missile.” Whereas antibiotics can kill good microbes along with the bad—often resulting in secondary infections—this technique results in fewer side effects according to Tblisi, Georgia-based Phage Therapy Center. But phage therapy’s biggest promise is also what gives it its real advantage over antibiotics: If a bacteria becomes resistant to a particular bacteriophage (or mixture of phages), new strains can be identified in days or weeks rather than the years it takes to develop a new antibiotic.

And now, Professor Martha Clokie and a team of scientists at Leicester University have identified phages that can treat salmonella and other common infections in pigs. The experimental therapy has proven successful in the lab, and the researchers have developed a powdered medicine that can be added to pig feed. They plan to test it on live pigs later this year. If successful, phage therapy could eventually be used to treat antibiotic-resistant infections in humans, Clokie told the BBC.

Phage therapy was a promising new treatment in the 1920s and the 1930s before antibiotics became widely available, Joanna Urban explains in mBiosphere, a blog published by the Journals of the American Society for Microbiology. Even after antibiotics went mainstream, parts of Eastern Europe continued to use the technique. Now, antibiotic resistance and the threat of superbugs have sparked new interest in the therapy.

But phage therapy is not without risk. In the past, its results have been somewhat inconsistent. And as Urban points out, a small subset of phages called “superspreaders” can actually help spread microbial resistance. (The researchers who identified the “superspreaders” told Urban that these phages were identifiable and merely something to be aware of; not all phages are capable of efficiently transmitting resistant genes.)

To date, there are no phage-based treatments approved for use on humans or animals in the United States. Still, in March of 2016, a patient near death with a severe antibiotic-resistant infection was given phage therapy in San Diego with emergency approval from the Food and Drug Administration. He lived.

Even if Clokie’s trial is successful, scientists have a long way to go before phage therapy can replace antibiotics in animal agriculture. But some day, therapy could stop superbugs on farms. Just don’t count on bacon with a side of self-awareness.