Noam Galai/Getty Images

The pandemic has transformed huge parts of the U.S. seafood system—from what consumers want to eat to the way fish reaches their plates—providing valuable lessons in what works and what doesn’t.

Not unlike its effect on humans, the pandemic’s impact on the seafood industry has been variable, erratic, often devastating. The first symptoms appeared long before Covid-19 gained a stronghold on U.S. shores, as China went into its first lockdown and a critical export market disappeared overnight—seafood processors and dealers in Maine saw international demand for lobsters temporarily vanish. Then as social distancing rules kicked in here, another major organ of the U.S. supply chain—restaurants, where most seafood purchases are made—fell limp. Then Covid outbreaks at processing plants caused the system to further buckle, leaving many fishermen with nowhere to sell their catch. Prices for many species plummeted. Some fishers gave up for the season, leaving boats tied up at the docks.

“It wasn’t worth it,” recalled Brian Pearce, a commercial fisherman based in Portland, Maine, who catches pollock, hake, and cod, and has barely fished since the pandemic started. “The price was to the point where you’re not going to make enough money.”

To many in the food industry, the pandemic’s impact has exposed the fundamental vulnerabilities of a system that has long favored efficiency over resilience. Like supply chains that draw products from many sources but are ultimately contingent on single outlets (e.g., export markets or restaurants). Or the fact that the majority of U.S.-caught seafood is exported to other countries, but—paradoxically—most seafood Americans eat is imported.

“I think in some instances, it’ll change for the better, especially for fishermen. But I’m sure that there are some fisheries [that] are going to be devastated. And whether or not they’ll be able to recover from this—that I don’t know the answer to.”

But the sledgehammer of 2020 also demonstrates what can make food systems more resilient to crises. Remarkably, consumers are experiencing a newfound appetite for locally caught, sustainable seafood. And accordingly, a slice of the U.S. fishing industry has fattened slightly this year: small, locally operated fisheries which have built their own supply chains to serve consumers, often delivering directly to their door. No strangers to challenges or disaster, many individual fishermen have also pivoted towards selling directly to the public—with mixed success. Yet what these lessons mean for the future of the industry—and if they’re enough to create resilient fisheries that can weather future storms—remains an open question.

Covid-19 will probably leave a long-term mark on the seafood industry, said Mike Conroy, executive director of the Pacific Coast Federation of Fishermen’s Associations. “I think in some instances, it’ll change for the better, especially for fishermen. But I’m sure that there are some fisheries [that] are going to be devastated. And whether or not they’ll be able to recover from this—that I don’t know the answer to.”

—

In March 2020, between the lush Tongass National Forest and the icy ocean in Sitka, Alaska, Kelly Harrell and her colleagues braced for the worst. As the coronavirus crept into the state, fishermen had seen some of the first fish prices of the season drop. But as chief officer of fisheries at the direct-to-consumer company Sitka Salmon Shares, Harrell and other company leaders figured they could provide the company’s 22 fisherman-owners some stability.

Since 2011, the company had maintained a business model where customers—who happen to be mostly in the Midwest—sign up to pay for three months’ minimum monthly “shares” of wild fish, along with recipes, delivered to their doorsteps via the company’s own supply chain. Pre-purchasing shares meant that when salmon prices tumbled during the summer, the company could guarantee fishers stable wages—20 percent over the going dock prices, on average. And surprisingly, Harrell and her colleagues, who expected to lose customers due to the instability caused by the pandemic, instead saw a surge in sales. “We’re very lucky that we’ve been investing and building this supply chain,” she said, adding that the company expanded its core group of fishermen last year.

The fact that consumers are flocking to community-supported fisheries (CSFs) like Sitka Salmon Shares, despite often cheaper imports in grocery stores, is a bright spot to Linda Behnken, executive director of the Alaska Longline Fishermen’s Association. Behnken also directs Alaskan’s Own, a CSF whose sales doubled last year. In addition to meeting increased demand for home-delivered food during the pandemic, this trend is also driven by similar factors to the rising popularity of community-supported agriculture (CSA) programs—CSF’s terrestrial equivalent—during this pandemic.

Fishing boats in Sitka, Alaska. Sitka Salmon Shares, a direct-to-consumer company, has customers sign up for monthly shares of wild fish which is delivered to their doorsteps.

Flickr/Dom Sagolla

With restaurants off the table, people embraced culinary adventures inside their own homes. And when the shelves in grocery stores ran empty, shoppers began questioning conventional systems and their social and environmental sustainability. “[CSFs] seemed like a good way to support independent and environmentally conscious fisheries, and also get a good supply of protein monthly without having to go to the grocery store,” said Chicago resident Michi Trota, editor-in-chief of Science Fiction & Fantasy Writers of America, who signed up for Sitka Salmon Shares last year. The shares start at $119 for 4.5 pounds of fish per month, which Trota said she could afford because she was no longer commuting to work. She has been happily making halibut ceviche and cured salmon ever since.

In fact, some direct-to-consumer fisheries across the country saw a spring bump in demand, according to a survey last year. Joshua Stoll, co-founder of the Local Catch Network, says that interest has cooled a bit since. Nevertheless Stoll, who studies alternative food distribution systems at the University of Maine, said a renewed interest in local food during a crisis isn’t surprising.

In 1917, Canadian officials encouraged citizens to grow food locally in “victory gardens” to boost food security during World War I. Similarly, Europeans started distributing food locally during the 2007/2008 financial crisis. Direct-to-consumer systems are not intentionally designed to be resilient to crises, but it is their design—bypassing the complexity of multi-player supply chains—that makes them more resistant to outside calamity, Stoll said. “There’s other types of shock that they’re not resistant to, but to [this] type of global systemic shock . . . I would argue they’re likely more resilient than many of these broader systems.”

Crisis history suggests that following bursts of localization, food systems give in to an irresistible tendency to re-globalize, and consumers forget.

Such systems also proved robust during the shaky trade relations between China and the U.S under former President Donald Trump. Six years ago, due to fears over unstable trade relationships like these, Kat Jones and her husband, a fisherman, decided to start selling California spiny lobster—a delicious species typically sold to China at high prices—at a dockside market in Ventura Harbor. That turned out to be a good call when China began to introduce retaliatory tariffs on American lobster in 2018, putting Jones’ CSF in a good place to meet the extra demand during the pandemic. She hopes to counteract what she sees as a backwards mentality of exporting America’s top produce, which she perceives as of higher quality than imported products. In her view, “we export the world’s finest seafood,” and with the exception of Japanese fish, she said, “we import garbage.”

The key question, though, is whether this newfound consumer interest will stick. Crisis history suggests that following bursts of localization, food systems give in to an irresistible tendency to re-globalize, and consumers forget. For local or regional food systems to counteract that tendency, they’ll have to outperform commodities markets, said Alan Lovewell, a commercial fisherman based in Monterey Bay who also runs the CSF Real Good Fish. The biggest obstacle may be price, which is where globalized food systems excel, because they’ve evolved to maximize profits. But still, Lovewell said, “I think there’s never been a more promising [time] for the local food movement.”

Covid-19 outbreaks at processing plants left many fishermen with nowhere to sell their catch. Prices for species plummeted and some fishers gave up for the season.

Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images

—

Many fishermen across the country have pivoted to direct-marketing models by selling their catch off their boats or taking advantage of state-driven “fish to dish” initiatives that distribute catch directly to people. Some have even created their own supply chains. As the U.S.-China lobster tariff war escalated in 2019 and continued into 2020, Craig Jacobs, a fisherman based in Huntington Beach, California, decided to sell his California spiny lobsters locally last January. He processed and hand-delivered all the orders himself until his sister Laila Bell set up a website to keep up with rising demand. They hired Jacobs’ two daughters and family friends to help.

Craig Jacobs

Last year, commercial fisherman Craig Jacobs in California launched the direct-to-consumer seafood company OC Wild Seafood, selling spiny lobster and other seafood, with help from his family.

When Covid-19 hit and restaurants closed down, Jacobs’s business—OC Wild Seafood—was well-equipped to meet a surge in demand, and also started selling ahi tuna, swordfish, and sea urchins caught by other fishermen. Bell left her job in the travel industry to help find a processing facility, set up a delivery service, and navigate food safety regulations—without her Jacobs said he “would have given up.” Still, his workload is a lot heftier compared to pre-pandemic times, his business is longer subject to the whims of geopolitical trade disputes, and he can demand better rates than wholesalers who often insist on large volumes at low prices. When asked by customers if he’s going to stop direct marketing once the pandemic ends, he insists, “We’re going to stick with it.”

Conroy reckons that overall, it’s a small percentage of California fishermen who set up direct-marketing during the pandemic, because of the extra work involved, both in terms of figuring out what permits and certifications are needed, and how to reach and sell to customers. “Most that I have seen who have been successful have a spouse or partner who have been ready, willing, and able to help,” he added. But the ones that have been able to do so have been pretty successful. Particularly for lower-volume, higher-value fisheries, such as salmon, tuna, and swordfish, “I don’t know how much of that is going to go through a middleman once the dust has settled on this pandemic.”

For other fishermen, direct marketing has overwhelmingly been a headache. In late March, many lobster wharfs up and down the coast of Maine stopped buying. Tom Santaguida, whose wharf typically sold to overseas markets, cruise ships, and restaurants, helped create a Facebook page, Maine Fish Direct, where individual fishermen could connect with buyers to sell their catch. In the spring, while he was catching a manageable amount of lobster, he’d meet up with eager customers and sell them the crustaceans directly, at a higher price than he could have sold them to the wharf. But making those connections, arranging, and delivering lobster to individual customers proved to be a brutal amount of work. Far from a silver lining, “It’s a pain in the ass, is what it is,” he said.

Direct-marketing was a short-term band-aid that became impossible once the lobster harvest took off in July. Lobstermen often have to make a year’s living in the span of five months. “There’s just no way you can spend 12 hours on the water, handle that many lobsters and then go peddle them before the next day.” Without a massive price increase, “it’s just not something that works,” he said. Not helping matters, under Maine law captains usually have to be the one who sells the catch—with some exceptions, crew members aren’t allowed to help. While Santaguida still sells to a select few, he steered away from direct marketing once the wharfs started buying again last summer. On the whole, he said, “It was just a horrible year.”

For commercial fishermen like Tom Santaguida, direct marketing was a headache. He and some other fishers created a Facebook page, Maine Fish Direct, where individual fishermen could connect with buyers to sell their catch.

Tom Santaguida

Another challenge is a frequent lack of infrastructure to support the direct marketing business model, Stoll said. It lacks things like public piers, hoists, ice machines and processing facilities—which are privately owned in many places—as well as a welcoming regulatory environment allowing fishers to sell directly to people. (Some areas forbid this practice outright, like Dare County in North Carolina.) “If we’re interested in learning from this pandemic and responding to it in the seafood sector, we should really think seriously about the physical and soft infrastructure that we need in place that not only doesn’t get in the way of, but enables this local and regional distribution,” Stoll said.

But there are some fisheries where a middleman may simply be necessary. Direct marketing has been harder for those working in low-value, high-volume fisheries, such as harvesters of groundfish—mostly bottom-dwelling fish—in Maine, who bring in thousands of pounds at a time. Pearce, the fisherman from Portland, who harvests groundfish species that are usually sold processed and typically to restaurants—said it’d be impossible without middlemen to find the time to harvest, process, and sell his catch. Interestingly, Ben Martens, executive director of the Brunswick-based Maine Fishermen’s Association, has seen some businesses pop up or transform to provide that missing link. He points to Gulf of Maine Sashimi in Portland, a wholesale dealer that normally buys from fishermen and sells to restaurants. Now they’re selling directly to consumers, he said. But ultimately, that’s not enough to sustain the industry. “We still need other places for the seafood to go,” he said.

Atlantic Rock Crabs caught by commerical fisherman Tom Santaguida on the coast of Maine.

Tom Santaguida

—

Many fishermen have found other ways to make ends meet, such as turning to different species when the markets for their typical catches vanished. Some, like Pearce, have relied on creative programs that help feed both fishermen and people. After receiving an anonymous donation of $160,000 last September, the Maine Coast Fishermen’s Association has been buying fish from a small group of groundfish harvesters at competitive prices and distributing it to local food banks in Maine—a state that has the highest food insecurity rate in New England.

Up in Alaska, Behnken has spearheaded similar programs to buy up vast quantities of seafood and feed hungry communities in the Pacific Northwest, Alaskan military bases, and Tribal communities in the state’s southeast. Although these initiatives have helped offset the pandemic’s impact, “For a lot of species it really wasn’t possible to keep prices from sliding,” Behnken said. Operating costs had increased as crews and processing staff had to be tested and quarantined to prevent the virus from getting into rural communities. Many fishers in Alaska accessed little help through federal aid programs, she added.

The pandemic hurts not just because it’s such an unprecedented shock to U.S. fisheries, but also because it’s the culmination of a long-term build-up of the uncertainty, anxiety, and stress that comes with fishing, noted Monique Coombs, director of marine programs of the Maine Fishermen’s Association. Commercial fishing already has many unknowns—you don’t even know if the fish will show up, and even if they do, whether you’ll get a good price for them, said Jacqueline Foss, who uses a hook-and-line technique to catch salmon near Sitka, which she sells to a fishermen-owned co-op processor. Over the years, the costs of insuring her vessel, fuel, and maintenance, have risen while prices have stagnated. “In a normal year it’s dicey. But this year was the pandemic, it was like an extra layer,” Foss said.

“The next big global disruption won’t necessarily be the same and won’t necessarily have the same impacts. So it’s really good for us to keep that buffer and diversity within the industry.”

Other fishermen stress the frequent burden of increasing numbers of regulations in the fishing industry. In a recent survey of over 200 fishermen in the Northeast, a third of respondents indicated they were unsure about whether they’d still be fishing in three year’s time, raising the question of whether some will leave the industry indefinitely.

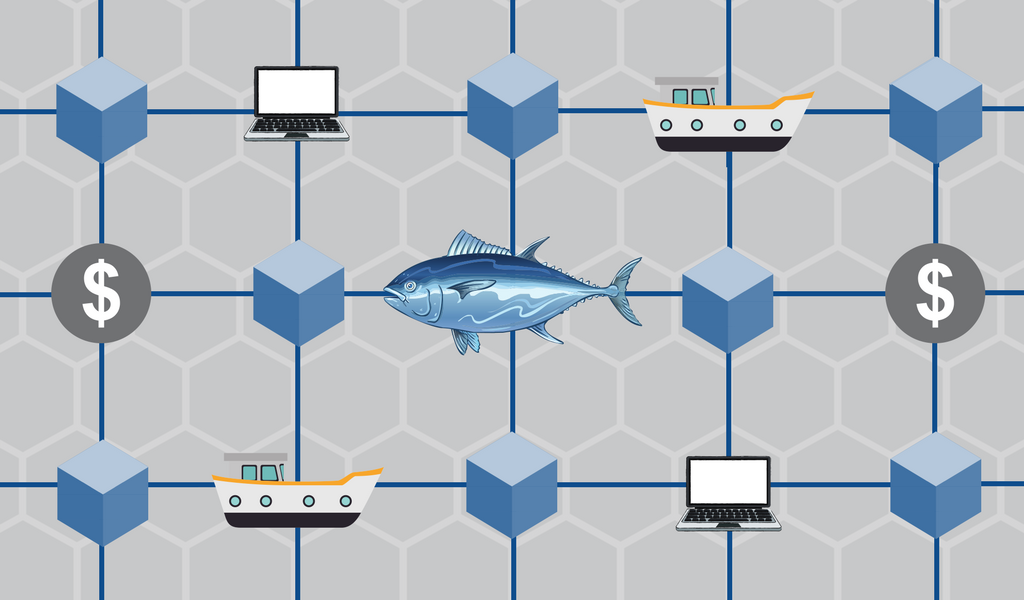

Direct-to-consumer sales can enhance the resilience of the industry as a whole and hopefully buffer some of the impacts as the U.S. hurtles through another pandemic wave. But they can’t replace large-volume processors and packers. Ultimately, a truly resilient system is a diverse one, so it’s less of an issue when one thing breaks, remarked Jessica Gephart, who studies seafood trade at American University. She envisages a system of small and large producers, processors, and distributors, building a variety of supply chains that target different groups of consumers and are less reliant on single outputs, like Asian export markets or restaurants.

“The next big global disruption won’t necessarily be the same and won’t necessarily have the same impacts. So it’s really good for us to keep that buffer and diversity within the industry,” Gephart said. To get there, perhaps the most actionable solution right now is to eat more American seafood. Both Pearce and Santaguida lament the fact that cheaper imported products find their way into American grocery stores and compete with what they catch. Gephart said, “There are most certainly portions of the U.S. market where [consumers] have a strong preference for locally caught seafood.” Especially for more processed products where the source and species are less apparent, though, price is likely a stronger driver. To Pearce, “That’s why our market is not as strong as it should be.”

The impacts of the pandemic have varied greatly across and within fisheries, depending on their timing, how the catch is processed and distributed, and local Covid-19 guidelines. While some parts of the industry are recovering, others are ploughing through a long winter. Their long-term recovery depends on the pandemic itself—whether everything resumes to normal once vaccines are distributed, or, as Martens and Coombs fear, whether the pandemic has economic ripple effects that will keep restaurants shut for a while. But it also depends on consumers, and whether their heightened collective consciousness around food systems lasts.

“I just hope that people aren’t so interested in returning to normal that they’ll forget the things that we learned,” Foss said. “I really hope some of the improvements that we’ve made stick.”