Claire Brown

Today, the National Organic Standards Board (NOSB) is meeting in Saint Louis. As I write this, carrageenan is still an acceptable ingredient in organic foods. But by the time you read this, that may have changed. There’s a good chance that by the time NOSB has wrapped up their business, they will have removed carrageenan from the National List of synthetic ingredients permitted to be used in food marketed as organic. There’s nothing wrong with that: Part of the board’s mandate is to gradually remove from the list ingredients that aren’t essential to food production. There are replacements available for most uses of carrageenan, which is used as a thickener and stabilizer, and manufacturers who truly can’t do without the stuff are permitted to petition for an exception. Everything by the book.

I’m not happy.

Here’s the problem. The legal authority to delist carrageenan will come from the fact that alternatives are available. That’s fine. But the rather large public debate that’s led up to the decision has been couched almost entirely in terms of food safety. And the NOSB shouldn’t be ruling on food safety. Certainly it is supposed to react when it knows an ingredient is unsafe, but it’s hard to see what qualifies this collection of producers, processors, and consumer advocates to make an independent decision on whether an ingredient is safe or not. It’s like letting Congress decide whether global climate change is real or permitting the Texas School Board declare that evolution is an open question. (I know, we’ve done both of those things, but do we like the results they lead to?)

Maybe I’m overthinking things, but if everyone on every side of the issue thinks they’re arguing about food safety, then they’re arguing about food safety.

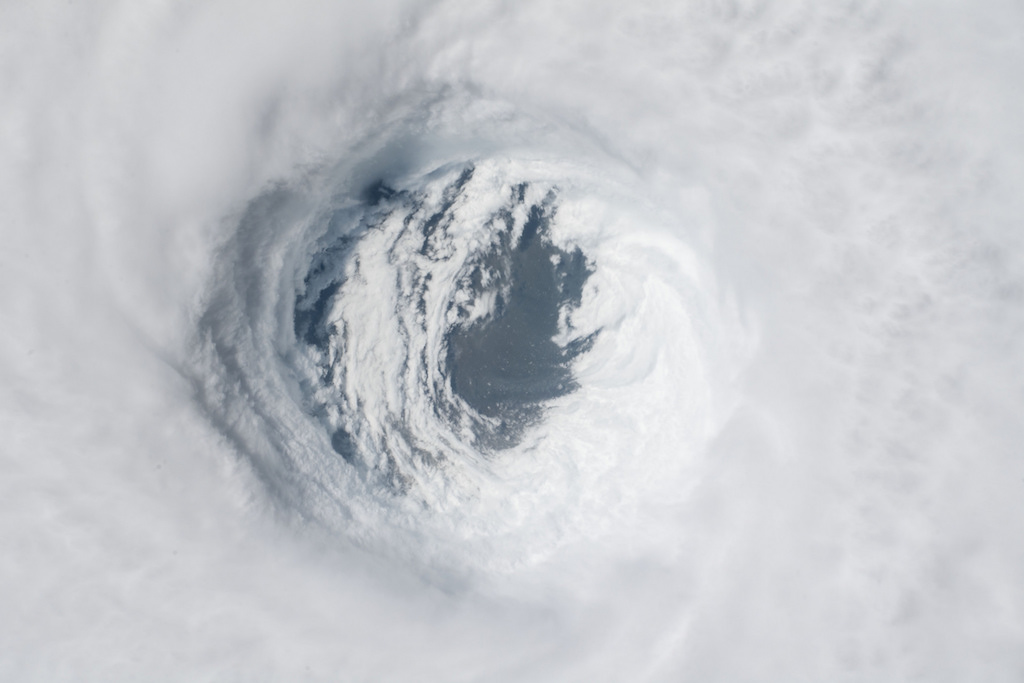

Carrageenan, a thickening agent, is derived from red seaweed

And food safety, though we all care about it, is not something that most of us can productively debate. We need agencies like USDA and FDA, and we need them to be trusted. Otherwise, every decision is nothing but politics. And if the past couple weeks have taught us anything, it’s that politics has a way of turning winners into losers overnight, and the winners aren’t always determined by objective reality.

And let’s acknowledge: Though we wouldn’t want to have public policy on things like food and drug safety regulated by anything but science, science is far from simple to interpret.

For instance, going back to carrageenan, if you read the recent piece on the issue in Civil Eats (which you should—you won’t find a better plain-language explanation of what people are concerned about and why), you might come away with the feeling that carrageenan is pretty bad stuff, that it causes dangerous inflammation in people who consume it, and it’s supported by only a few producers and their lackeys. Fair enough—that’s actually a reasonable way to interpret the facts. But there’s another reasonable way to interpret the facts, in the report issued by the Handling Subcommittee of NOSB, which makes recommendations on what stays on the list and what goes. On carrageenan, it says, in part:

The Handling Subcommittee does not currently have definitive evidence on whether carrageenan is in fact a synthetic ingredient. It has commissioned a study, but it appears that the NOSB will make a decision on whether it is an approved synthetic ingredient before receiving an answer.

- The report states: “The NOSB Handling Subcommittee is aware of research that came to our attention in the sunset review of other emulsifiers such as lecithin and guar gum which suggested that all of these ingredients may be contributing to metabolic syndrome, inflammatory bowel disease and obesity, simply by their impact on microbes in the gastrointestinal tract. This had been supported by previous research on Crohn’s disease. While carrageenan has been more extensively studied than the other non-synthetic emulsifiers, there may be reason for concern that all emulsifiers can lead to inflammation and it is not a unique function of carrageenan.”

- In the report, the subcommittee reiterates its concern that much of the evidence on carrageenan and inflammation comes from a single lab and has not been replicated. One recent study that attempted the task reported: “The present work has shown that CGN [carrageenan] does not cross intestinal epithelial cells, and is not cytotoxic to these cells. CGN did not increase cellular oxidative stress nor did CGN induce the expression of proinflammatory genes.”

Let’s talk a bit about that last point. The most significant research supporting the idea that carrageenan causes inflammation is not what you might expect: a clinical study in which human subjects are fed either carrageenan or a placebo, and researchers measure who gets inflammation and who doesn’t. Instead (to oversimplify somewhat), researchers expose human cells to carrageenan in vitro and analyze the various proteins they produce. It’s a powerful approach, but it presents some problems; we don’t entirely know how to extrapolate from the in vitro results to what would happen in a living body. (One reason: Many of the cells used in research are not “normal” cells; they’re cultures created from human cancer cells. How much difference does it make? We’ll get back to you on that, eventually.)

The problem here was bigger. The team doing the replication study got basically none of the result the original team got. Their cells wouldn’t absorb or interact with the carrageenan at all. They generated none of the inflammation products the original studies did.

Does this disprove the original studies? Nope. But if we trust that the methods and results of the second study were honestly reported, it makes us ask why the results were different. And it should make us recognize that we won’t entirely understand the original studies until we answer that question.

The study, by the way, was funded in part by FMC Corporation, which manufactures carrageenan, and by the International Food Additives Council (IFAC), which will cause many people to dismiss it out of hand. This kind of reaction is reasonable, but it makes me feel like many people have no idea how deep conflict of interest goes. Sure, the researchers who cashed FMC’s check may have felt some pressure to deliver acceptable results. But if you’ve ever lived in an academic setting, you know that the lead author of the original studies, Joanne Tobacman of the University of Illinois at Chicago, having built some solid research turf around carrageenan and inflammation, had more to gain from confirming her early work than from proving that she’d been wrong. And the folks at Cornucopia Institute, which has campaigned aggressively against carrageenan, and whose work I admire, have an interest in being seen as lonely crusaders fighting against entrenched corporate interests. And I have an interest in coming up with off-center interpretations of events and enticing you to read. All of us have reasons to say things that aren’t quite so. All of us, if we’re being even reasonably professional, fight the impulse, with greater or lesser success. It’s not a perfect system, but it’s what we’ve got.

Again, it may sound like I’m overthinking it. Maybe so. But as I said, the last few weeks have me thinking. I’ve witnessed the spectacle of an enormous number of my fellow citizens apparently deciding that facts are infinitely malleable. I’ve watched authority rejected and authoritarianism embraced. I’m feeling a deep hunger for reality. I know it’s not simple, and that we approach it only by building and sustaining institutions that we trust.

Here’s a little thought experiment: Let’s say that a few years hence, FDA reviews all the evidence on carrageenan (or the ingredient of your choice). After long and transparent proceedings, the agency comes up with a conclusion about its safety exactly the opposite of what you’ve always believed. Do you accept the decision, confident that if it is wrong, it will ultimately get corrected? Do you accept a duly constituted authority? (This doesn’t mean that you agree, just that you accept.) If not, what do you do? Can we in fact continue to protect each other from the world’s dangers if we can’t have a mechanism for making decisions?

That’s not actually meant as a rhetorical question. I’d love to hear your thoughts. Send them to [email protected].