You may have heard that virtually all bananas we eat are from the genetically identical Cavendish cultivar. You’ve also likely heard about a big, scary disease called Fusarium Wilt (also known as Panama Disease) that evolved to threaten the previously resistant Cavendish. (Panama Disease basically knocked out the last great banana cultivar, the Gros Michel—French for “Big Mike!”)

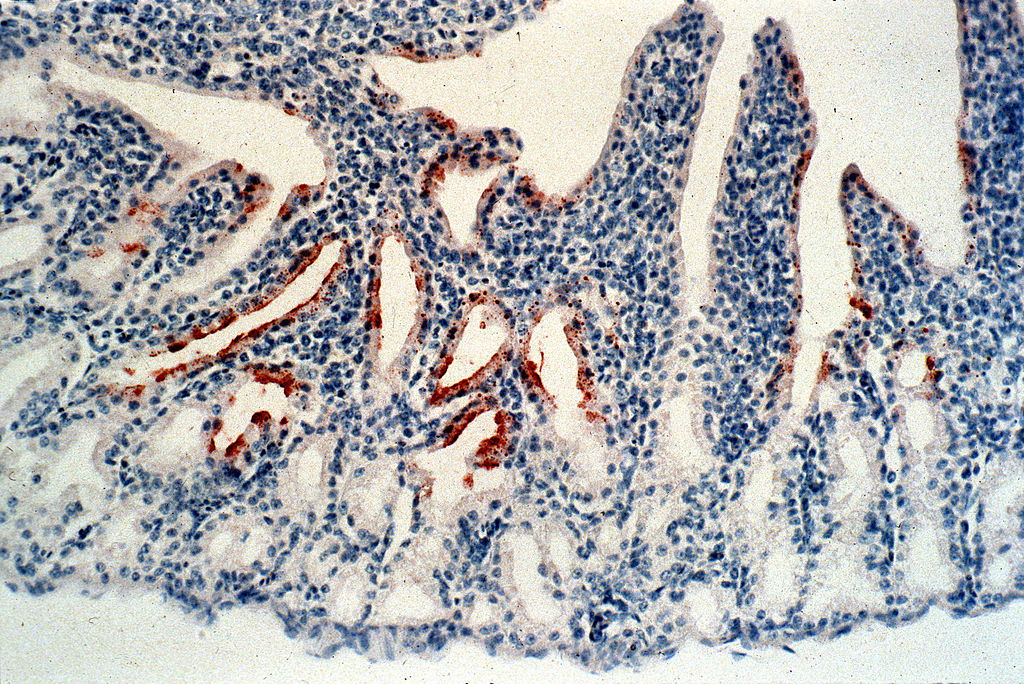

Unlike Fusarium Wilt, Black Sigatoka does not kill off entire banana farms. Rather, it affects the plant’s leaves, which can in turn interrupt the fruit ripening process and depress yield by up to 80 percent, according to the study.

Scot Nelson

Scot Nelson Photo of a tree in Hawaii affected by Black Sigatoka

Black Sigatoka can be controlled by fungicides, but Bebber says it develops resistance very quickly. Farmers have to spray many times over the course of a growing season, switching chemical formulations often. It’s expensive and increasingly environmentally unsound. “For sci-fi fans, it’s like fighting the Borg,” he adds. (I had to look it up—it’s a group of cyborgs in Star Trek that adapts to changing conditions with great agility. Checks out.)

Since it was first identified in Honduras, Black Sigatoka has spread to Latin America, the Caribbean, and even parts of Florida. And while the study acknowledges that humans certainly had a hand in spreading the fungus via trade routes, climate change has clearly aided in its spread and survival. Though the study does not make any predictions about the future of the fungus, it stands to reason that rapidly-evolving fungicide resistance coupled with a changing climate may mean it won’t go away on its own.

“Black Sigatoka is definitely a forgotten disease [but] it costs banana growers hundreds of millions of dollars to control … we urgently need more research to develop sustainable, affordable solutions,” Bebber says.