Jenny Shinn

Update, 3:35 p.m., EST: This piece has been updated to include additional information about third-party certification.

You may have heard this centuries-old maxim about when it’s safe to eat raw oysters: Don’t indulge in the bivalves during any month spelled without the letter “R.” (Though, there’s plenty of cause to consider the maxim suspect.)

If you’re like me, you’ve largely disregarded this rule in favor of your own self-interest. But if you’ve been heeding it, then you’re likely just beginning to rejoice in the dawn of oyster season.

This fall, there’s another reason to revel in the oyster harvest, beyond its sheer gustatory pleasure. If you eat an oyster today, its shell may not necessarily end up in landfill, as it would have in the past. Instead, it may be redeposited back into the waters from which it came, to serve as a home—or even a castle—for future oysters to come.

In the past few years, a surge of oyster shell recycling programs have emerged in coastal regions. Some are state-run, like the South Carolina Oyster Restoration and Enhancement Program (SCORE). Others are specific to certain bodies of water, like the Galveston Bay Foundation’s Oyster Shell Recycling Program in Texas. And some, like the New York-based Billion Oyster Project, are run by high-school students.

“When you harvest an oyster, essentially you harvest its habitat right alongside it,” says Dr. Jennifer Pollack, chair of the Harte Research Institute for Gulf of Mexico Studies at Texas A&M University-Corpus Christi. “If you’re going to go fishing, you go and catch a fish, but you don’t remove the water with it. But for oysters, the way that reefs are built is essentially: The younger generations of oysters cement and attach themselves onto the shelves of the older generations of oysters that form the foundation of the reef.”

This means that when oysters are removed from the water in service of dollar-oyster happy hours, gone too are their calcium carbonate shells, which would have become the substrates that house future generations of oysters. And that’s where oyster shell recycling comes in.

Jenny Paterno Shinn

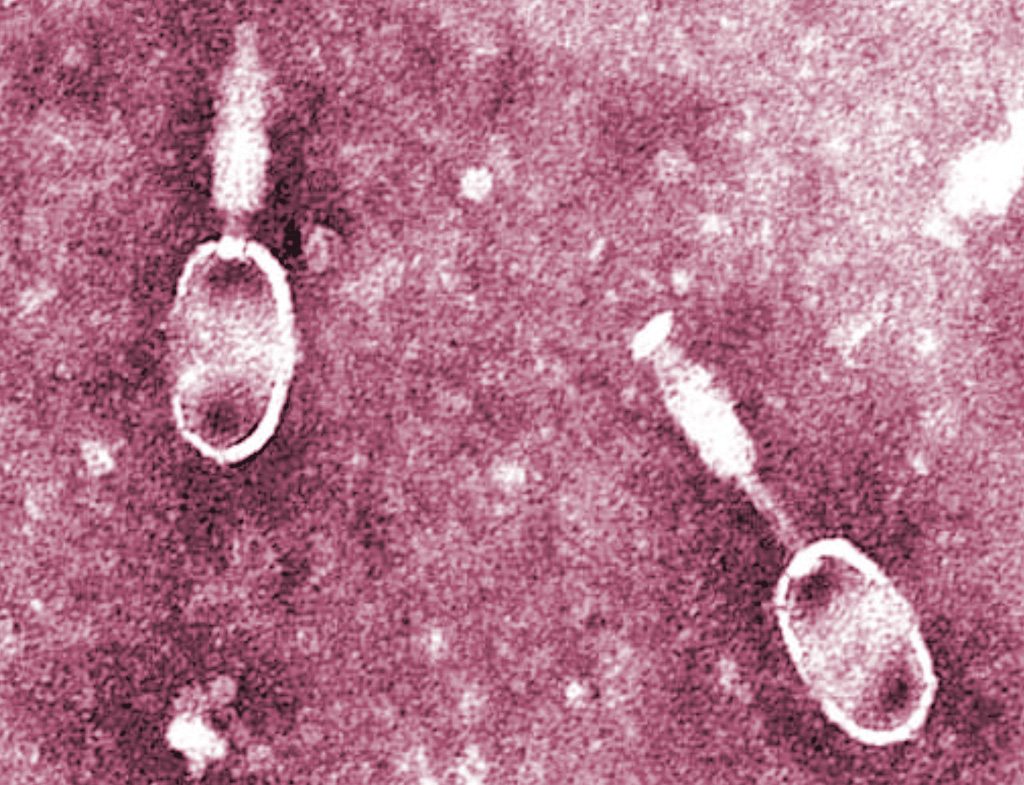

Jenny Paterno Shinn Photographed here are bagged oyster reefs in the Delaware Bay. The shells are collected, placed in mesh bags, then lined along shorelines to spur the growth of new reefs

In Maryland, restaurants can donate their leftover oyster shells in drop-off bins located throughout the state. Run by the Chesapeake Bay Foundation, a nonprofit that supports restoration efforts in the area, these shells are washed clean of debris and then bathed in sunlight for six months to kill potential pathogens.

“That quarantine period where they sit out in the sun is just to protect the Bay [from any] transfer of disease or parasites or predators that may have come from a different system,” Pollack says.

The shells then get dumped into big fish tanks populated by oyster larvae—or “spat”—which attach to the shells and begin to grow as they would in their natural environment. Becoming spat is a crucial step in oyster development. Without shells on which to plant, larvae usually sink to the bottom of their marine environments and die.

The Chesapeake Bay Foundation redistributes spat to oyster gardeners and pours them into waterways where oyster reefs used to be.

In the Delaware Bay in New Jersey, researchers at Rutgers University’s Haskin Shellfish Research Laboratory are adding one more step to the restoration process: They’re constructing oyster castles.

Oyster castles are built from blocks made from a mixture of recycled shells and concrete. They are the structure that oyster larvae can plant onto and grow

Oyster castles are a matrix of interlocking blocks stacked onto each other. The blocks are made from a blend of concrete and oyster shells. Unlike simply pouring spat into water, these castles give oyster reefs a scaffolding to grow on, which can come in handy when there aren’t enough shells to start a reef.

“The main draw for oyster castles is that you can get height with them, you can build them in any configuration you want, kind of like Legos,” says Jenny Shinn, a program coordinator at the Haskin lab. “You can stack them on different shapes and different heights. When you’re trying to reduce wave energy, you need certain heights.”

Over the course of eight months in 2016, the lab raised oyster castles along Gandy’s Beach and Money Island on the Jersey Shore. The process was long and arduous, in part because construction was at the mercy of fluctuating sea levels. Concrete blocks were shipped by barge during high tide, then built into castles by hand during low tide. Castle placements were determined by engineers, who calculated the height that castles needed to reach in order to break currents, based on their strength and direction.

Since 2016, three generations of oysters have made Haskin’s oyster reefs their home. And they’ve got neighbors, too.

“It’s proving to be kinda like a nursery habitat,” Shinn says. Had the castles not been there, the surrounding sea life would have just used a different habitat.

“This is more preferable because of extra food that’s here. There might be little crabs and shrimp eating the oysters, or barnacles on the castles. And then you’ll get some larger fish coming to eat those shrimp. And crabs use that as a foraging habitat.”

Nature’s own plateau de fruits de mer.

Jenny Paterno Shinn

Jenny Paterno Shinn Researchers from the Haskin Shellfish Research Lab at Rutgers University mark out monitoring transects on an oyster castle reef before counting juvenile oysters. The structure, shown a low tide, was in its first year of deployment and thus, not yet colonized heavily by shellfish

In Louisiana, oyster reefs do more than simply sustain oyster populations. They also help to protect the state’s coastline from erosion due to rising sea levels.

The Coalition to Restore Coastal Louisiana is a nonprofit focused on protecting the state’s coastal habitats. It runs an oyster shell recycling program, in which restaurants pay $100 a month to get their leftover shells collected, instead of sending them to landfill. The coalition uses the shells to build reefs in areas that are particularly vulnerable to erosion, like the Biloxi State Wildlife Management Area, off the tip of the state’s eastern coast. It’s a 35,000-plus acre marsh checkered by numerous bayous and lagoons, and home to crab, shrimp, and trout. Protecting it is an oyster reef 2,500 feet in length that was deployed by the coalition.

This self-sustaining growth is why oyster reefs are known as “living shorelines.”

You may be wondering whether we should just stop eat oysters. Is every slurp of these briny, beautiful bivalves a means to the destruction of their habitats?

“I definitely wouldn’t want to dissuade people from eating oysters,” says Chris Moore, a senior scientist at the Chesapeake Bay Foundation. “Aquaculture oysters and oysters that come from well managed wild fisheries are both ways that you can also help bring oysters back.”

But it can be tough to spot an oyster from a well-managed wild fishery on a restaurant menu. Monterey Bay Aquarium’s Seafood Watch program can provide some guidance on which oysters to eat, and which to avoid. Likewise, Food Alliance operates an independent verification program for farmed shellfish operations, with consideration to environmental impact as well as labor practices. The program has certified three suppliers so far. However, most restaurants serve farmed oysters, and if you’re eating farmed oysters, you can feel good that choice.

“Shellfish farming is becoming increasingly common and is the source of the bulk of shellfish,” says Matthew Buck, director of Food Alliance. “Generally, shellfish aquaculture is a pretty environmentally positive form of a farming.”

But what if you’re at a restaurant that doesn’t list its suppliers? In cases like that, your best bet is to ask your server about how the restaurant’s oysters are sourced. There are plenty of chefs who have close, personal relationships with their suppliers. There are also plenty of dollar oyster deals that may be more questionable.

To get a step further, you can even start your own oyster garden. In many states, there are programs that teach residents to raise oysters at home, before donating them back to the water. When it comes to oysters, you can easily give what you get.