Tommy Coyote Photography

When Brian Peterson-Roest decided to leave suburban Lake Orion, Michigan, he thought his beekeeping days were numbered. He was moving to Detroit. Who had ever heard of keeping bees in a city?

But his thinking changed on a trip to New York City, where saw hives of bees living in harmony with passersby in Manhattan’s Battery Park.

“I was like, why can’t I do bees in the city?” he says. “There’s so many green spaces and urban gardens and parks and abandoned lots in Detroit compared to most large cities. It just made sense.”

Two years after moving, in 2016, Peterson-Roest started keeping bees on the rooftops of friends’ businesses in Detroit. That year, he and his husband—who is also named Brian, though his last name is Roest-Peterson—co-founded Bees in the D, a nonprofit that promotes honeybee health and education. Today, Bees in the D manages 50 hives in the core of the city.

A non-native species that arrived in the United States with European settlers in the 17th century, honeybees are just one of 4,500 bee species in North America, says Matthew Shepherd, director of communications and outreach at the environmental nonprofit Xerces Society. They play a crucial role in the survival of crops—from tomatoes and blueberries to squash and almonds, a full third of our food—that require pollination to grow. Farmers have long trucked honeybee hives from field to field, using them like professional pollinators-for-hire.

But thanks to a range of factors, including pesticides, parasites, and fungal pathogens, they’re now in trouble. Between spring 2016 and 2017, a third of the honeybee colonies in the U.S. were lost.

Now, urban beekeepers are finding that cities may play in an important role in restoring honeybee habitats—and that human communities may benefit from their company.

People think of beekeeping as a rural pursuit, but honeybees can thrive in urban areas. Comprehensive studies on urban beekeeping are limited, but data in specific geographies from Boston to London suggest that bees actually do better in cities than in rural areas.

“Honeybees do OK in urban areas because their nesting strategy includes spaces that you can find in the city,” says Jennifer Leavey, director of the Georgia Tech Urban Honey Bee Project. Honeybees are cavity nesters, so they can find a home in spaces in walls, for instance.

Bee Downtown

Bee Downtown Cities have fewer predators, such as skunks, than rural areas. And abandoned lots aren’t treated with pesticides

“There’s a lot of wasted space in a city if you really think about it,” Peterson-Roest says. “The rooftops are really for the most part rather wasted spaces, which is a great space to put hives.”

Plus, cities have fewer bee predators (like skunks) than rural areas do. And abandoned lots aren’t typically treated with the pesticides that weaken honeybee health.

“The levels of pesticides and fertilizers is much higher in a rural setting because of people treating their crops or in suburban areas,” Peterson-Roest says. “Everybody has to have the best-looking lawn, and they spray for those dandelions and want to make sure that their yard is weed-free. But nobody is spraying the abandoned lots and the organic gardens.”

Urban environments also provide diversity in food sources for bees, says Leigh-Kathryn Bonner, founder and CEO of Bee Downtown. Her company, founded in 2015, places and maintains beehives on corporate campuses in urban areas, collecting data from the hives and keeping them healthy. So far, Bee Downtown has installed 170 hives for 50 companies in Georgia and North Carolina.

“Instead of being fed only one food source at a time and then being moved for pollination to another farm with another food source, these bees have a balanced diet,” she says.

That helps solve a major issue for honeybees: malnutrition. Bees need to feed on a variety of pollen sources to stay healthy, just the way human beings can’t just live on ice cream and coffee. But when used to pollinate vast, undifferentiated fields of row crops, they can struggle to get the nutrition they need. Urban areas, on the other hand, have unique ecosystems with varying levels of plant diversity. Leavey says bees do well in Georgia Tech’s home of Atlanta, which has lots of large urban parks and is the most tree-covered major city in the U.S. Peterson-Roest says the urban bees that Bees in the D tracks are more productive than ones in orchards, meaning that they have larger populations and make more honey—perhaps thanks to Detroit’s abundant gardens and green spaces.

Then there are the benefits to bees’ human neighbors. Leavey points out that urban produce growing requires animal pollination, so having bees nearby will increase that yield. Honeybees forage one to two miles away from their home, and in most cities, that radius includes a park or garden. Bonner says bees affect the 18,000 acres surrounding a hive.

“We’re seeing this huge shift back to urban agriculture and small, sustainable farming,” she says. “Those bees, if they’re in that radius, they’re positively impacting all of that. So that makes a big difference in the community. You might not see the bees up in the trees pollinating, but they’re there.”

Bee Downtown

Bee Downtown Urban beekeepers must act responsibly so the bees don’t create problems for native species or become pests to people

Peterson-Roest says gardens around beehives in Detroit have reported increased crop yields, benefiting the residents and soup kitchens that these gardens feed. He says the honeybees also help plants that humans don’t eat.

“Think about that: How many more people are being fed and learning about healthy eating,” he says. “The bees have a little bit to do with that.”

It has also led to a surge in interest, making people more hesitant to kill or spray bees once they learn about their importance.

“They’re not being sprayed because somebody thinks, ‘Oh my gosh, they’re going to attack me,’” Peterson-Roest says. “[People] understand that honeybees are actually rather docile creatures.”

Leavey says beekeeping helps increase environmental awareness, a factor that the Georgia Tech Urban Honey Bee Project studies. And bees make a good barometer: Their health tells us a lot about an ecosystem’s overall well-being.

“The weight of a honeybee hive directly correlates to the amount of nectar that’s available for bees, which correlates with weather patterns, climate change, land use change and things like that,” she says. “We study bees more as their health is reflective of the environmental health.”

Still, urban beekeepers must act responsibly so the bees don’t create problems for native species or become unwanted pests, Leavey says. It’s important that they make sure hive sites are well-situated, not in the path of people or a sidewalk, and that the number of hives is compatible with the neighborhood. Bees also require water, so it’s best that that urban keepers provide a water source so bees don’t seek it in a neighbor’s pool. (Peterson-Roest notes that Detroit stands close to a water source.)

“If beekeepers do a good job of educating their neighbors about the benefits of bees, and how the bees are not going to be dangerous to them, and what has to be done to remove bees, then it can all work out well,” Leavey says.

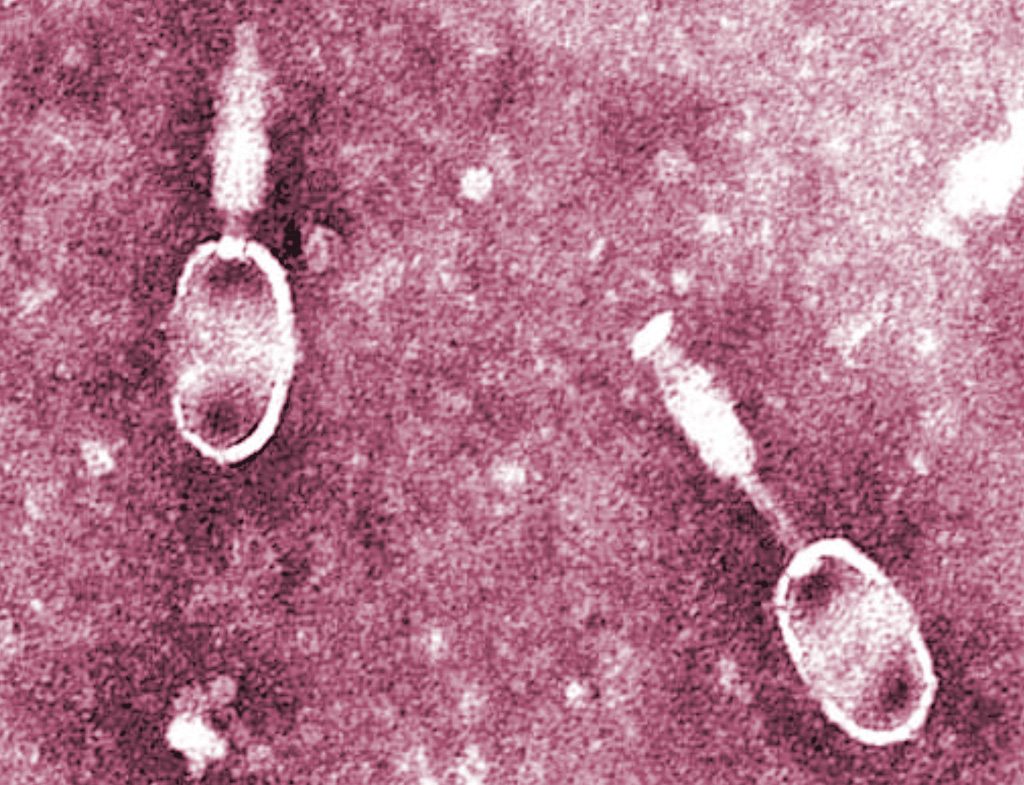

She adds that beekeepers have to keep the varroa destructor, a mite responsible for some of the colony losses, under control because it can be transferred between hives and from honeybees to native species.

Beehives may be a good fit for corporate campuses, too. Bees in the D has hives on top of General Motors’s headquarters and even converted the casing of a landfill-bound Chevrolet Volt into a beehive. It’s a way for companies to play a role in the ecological health of their communities, while delighting employees and getting some good PR. In Southeast Michigan, Bees in the D has worked to build a “bee highway” across a network of building rooftops, partnering with businesses to provide native wildflower waystations for pollinators.

Ultimately, urban honeybees are only one pollinator among many. But Bonner says they’re an important part of the equation, uniquely suited to the cities that can benefit from their presence.

“It’s not a quick fix to the problem of bee decline by any means,” she says, “but it’s a sustainable approach to helping increase their health, which will then increase our health.”