USDA/Lance Cheung

From unsafe food to election ethics violations—a new congressional report scrutinizes the agency’s $6 billion Farmers to Families Food Box program.

Under the former Trump administration, the Department of Agriculture (USDA) made millions of dollars in payments to unqualified hunger relief contractors despite multiple warnings of potential fraud, according to a new congressional report. The findings stem from a year-long investigation by the U.S. House Select Subcommittee on the Coronavirus Crisis into the Farmers to Families Food Box program.

The report lends new evidence to previous allegations that the taxpayer-funded program paid contractors well over market price for food, placed undue burdens on already-taxed food banks and pantries, then failed to conduct sufficient oversight on the contractors it flagged for potential fraud. It cites reporting from The Counter extensively.

“While the Trump Administration designed the Food Box program in a manner that would support agriculture and contractors, the program was not appropriately structured to meet its other primary goal: delivering healthy food to Americans struggling in a pandemic-induced economic crisis,” the report reads.

“While the Trump Administration designed the Food Box program in a manner that would support agriculture and contractors, the program was not appropriately structured to meet its other primary goal: delivering healthy food to Americans struggling in a pandemic-induced economic crisis.”

According to investigators, USDA approved millions of dollars in payments for deliveries that it could not verify had actually taken place. Thus, money meant to alleviate hunger during the public health crisis may have done little more than line the pockets of unscrupulous contractors. The report also stressed that the agency ignored multiple red flags, painting USDA as negligent at best or complicit at worst in the program’s mishandling. In addition to these shortcomings, investigators found that the program was misappropriated for the Trump administration’s political aims. The report found that multiple officials, including the former president’s daughter Ivanka Trump, wielded the program as a tool in Trump’s re-election campaign.

House investigators took a close look at three contractors who were hired for the first round of food box distribution, which began in the spring of 2020. It found that one distributor, Yegg, Inc., charged the agency 50 percent more than it paid dairies for product and deliveries, a huge profit margin for an emergency food aid program. Worse, Yegg pressured food pantries to accept more milk than they could give away, threatening to blacklist them if they declined deliveries that were too big. As a result, paid-for gallons of milk were wasted.

The USDA’s continuous favorable treatment of Yegg raises major red flags about the agency’s oversight of the program. In one case, the agency paid double the agreed-upon rate after approving an obviously erroneous invoice. In another, it approved invoices for deliveries that allegedly went to several different nonprofits—but which were all signed for by the same person, the vice president of a travel organization. The USDA even reimbursed Yegg for $2.85 million in deliveries to a nonprofit called Helping Feet, which was operated out of the same office space as Yegg by the wife of the company’s owner.

Despite receiving one of the program’s biggest contracts, CRE8AD8 had little experience in food distribution.

It’s not clear that Yegg even delivered all the milk it was paid for. On the day before its contract period ended, the company charged USDA more than $1.7 million for a single shipment of milk to Helping Feet. Under questioning, Yegg CEO George Egbuonu admitted that the deliveries were not made before the deadline. For its part, USDA knew the milk was still at the dairy, but paid out the invoice anyway. USDA never followed up to ask for proof the milk was purchased and distributed. Investigators who interviewed Egbuonu later learned that the company had no paperwork for $844,000 worth of milk it claimed to deliver after the deadline.

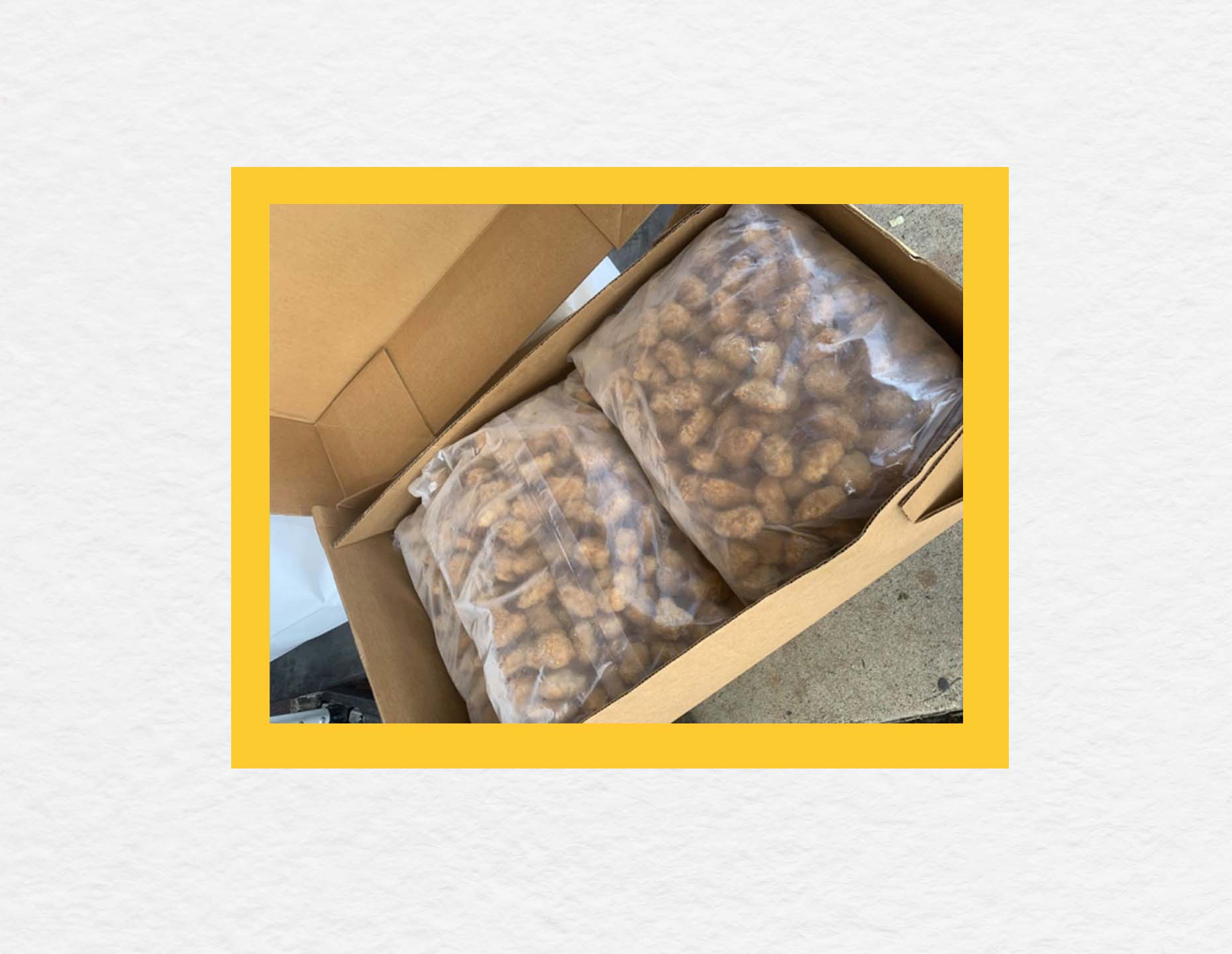

Investigators also scrutinized a contractor based in San Antonio, Texas, named CRE8AD8, finding that the company distributed poultry and meat to food banks that likely violated food safety standards. Despite receiving one of the program’s biggest contracts, CRE8AD8 had little experience in food distribution. (Pre-pandemic, it worked as a wedding planner according to its website.) Food banks said that the company initially tried to enlist limousine companies to deliver meat, and that instead of family-size servings, CRE8AD8 primarily distributed protein in five-pound packages—the kind that might be used by a cafeteria, rather than an individual. According to the Central Texas Food Bank, one of the organizations that received food from CRE8AD8, the company failed to keep frozen meat and perishables within required temperature ranges, and delivered boxes that fell apart, resulting in wasted product. The Counter reported much of this back in September 2020. When criticized by the head of the San Antonio Food Bank, CRE8AD8 threatened to stop deliveries to the organization altogether.

CRE8AD8 delivered a box of peppered chicken to the Central Texas Food Bank. However, because it wasn’t sent within required temperature ranges it was ultimately wasted.

U.S. House Select Subcommittee on the Coronavirus Crisis report

One of the odder subplots in the food box saga was USDA’s approval of Ben Holtz Consulting, also known as California Avocados Direct, for a $40 million contract. The agency issued a stop work order for the company, a small avocado mailing service, before it ever delivered any boxes. Yet the House report raises further questions about why the company was approved in the first place. In a section on the application that asked for references, someone applying on behalf of Ben Holtz Consulting wrote “I don’t have any” by hand. (Interestingly, Yegg later charged the government $42,000 for milk delivered to the address of California Avocados Direct, claiming the boxes went to an organization called S.M.A.R.T. Moms.)

Despite the program’s shortcomings, the report found that Trump administration officials repeatedly used it as a tool in the president’s re-election campaign. At one point, then-Secretary of Agriculture Sonny Perdue used an event promoting the program to stump for Trump, which the Office of Special Counsel later found to be illegal under the Hatch Act (a law that prohibits federal employees from using their official authority to influence election results).

Investigators also reviewed emails from the office of Ivanka Trump suggesting that every box include a letter signed by her father. Later, USDA then made Ivanka’s idea mandatory, sparking criticism from both government watchdog groups and food banks, who worried that such messaging could jeopardize their non-profit status. The agency did not disclose how much taxpayer money it had spent drafting and distributing the letters to investigators, who concluded that White House officials appear to have “manipulated the food box program for political advantage.”

The Biden administration wound down the Farmers to Families Food Box program at the end of May after it ran for a full year. The report recommends that USDA’s Office of Inspector General conduct a comprehensive review of the program and refer any potential fraud to appropriate law enforcement agencies.