Update, July 25, 4:05 p.m., EST: This story has been updated to include historical data about financial assistance to farmers.

On Thursday, President Trump will head to Iowa to meet face-to-face with soybean farmers, and tell them that even though buyers from their biggest importer, China, are thinking about canceling a huge fall order, it’s all going to be okay. The Washington Post reported on Tuesday that he will extend $12 billion in emergency assistance to farmers through three mechanisms in the Department of Agriculture—direct assistance, a food purchase and distribution program, and a trade promotion program. It’s a plan he’s said to have been working on since April.

The majority of the subsidies will go to soybean farmers, agriculture department officials said on a conference call on Tuesday. The direct payments, which the department characterized as a “one-time program” intended to bridge the gap until new trade partners are found, will be made to wheat farmers beginning in September, and soy farmers in October, after their harvests.

How big are these payments? “Unprecedented as a supplemental assistance program,” Joseph Glauber, who was USDA’s chief economist from 2008 to 2014, told me in an email. Commodity programs already authorized by Congress, which include price and income supports, conservation programs, and crop insurance, typically run around $20 billion a year. But “ad hoc” assistance, like the kind expected to be ordered by Trump, tends to be a lot smaller: The Obama administration paid around $250 million to cotton growers in 2014, for example, to bolster their prices. A more apt comparison might be disaster relief, like the $5 billion Congress authorized for drought-stricken farmers and ranchers in 2002.

We can’t necessarily manage a soybean surplus the way we do other agricultural surpluses. In the case of a dairy surplus, for example, the U.S. government purchases the surplus and keeps it in storage in the form of cheese. As Vox has reported, before 2012, that crudely named “government cheese” went largely unconsumed. But in 2016, the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) under then-President Obama announced it would buy up millions of pounds of cheddar to deliver to food banks and other food assistance programs.

Other surplus commodities get turned into school lunches. In 1995, USDA bought $30 million worth of pork for the National School Lunch Program (NPS). More recently, the agency purchased $126 million in fruits and vegetables to be distributed as emergency food assistance at food banks and soup kitchens. Surpluses for those commodities, along with poultry and fish, are directed under USDA’s Section 32 Program for farm and food support, a permanent appropriation since 1935 used to purchase agricultural commodities not generally covered by other mandatory farm support programs. The premise, according to a 2016 Congressional Research Service report, is that “removing products from normal marketing channels helps to limit supply and thereby increase prices and farm income.”

From the Great Depression through the 1980s, the U.S. government dedicated “bin space” for huge stocks of animal feed—like wheat, rice, and corn—and for oilseeds and cotton, in order to keep market prices up. Under New Deal policies, those reserves were called “government granaries.” Later, in million-bushel reserves, the grains were stored in fields of steel bins. This, too, was a way for the government to influence prices, by taking the commodities off the market.

“The big period was the ‘60s, ‘70s, ‘80s, when we had really large government stock programs,” says Glauber. “In the past, at least, when you had these storage programs, they had very specific rules that you couldn’t bring it back unless the price was above a certain amount, and so … a lot of them not only had support prices where the commodity would be bought or turned over to the government, but then also release prices, which were defined as some percent of the support price.”

Due to a surge in “world prices,” the government has been out of the grain storage business for about two decades, Glauber says. Ever since, the government has supported grain farmers with direct financial assistance—very much akin to what President Trump apparently plans for at least part of the $12 billion in emergency aid he’s expected to deliver.

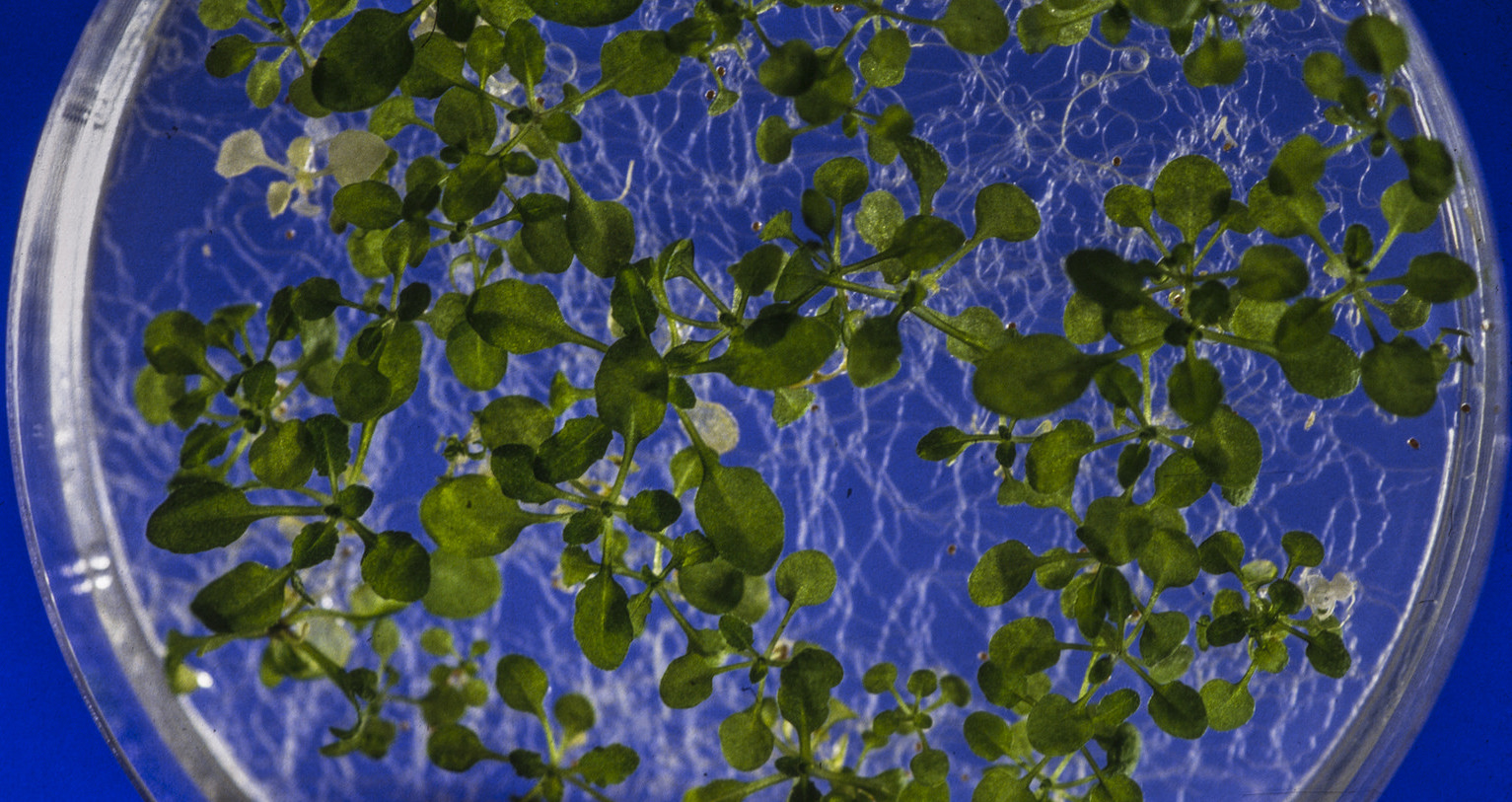

Under the New Deal, the U.S. government stored surplus commodities in “government granaries,” as photographed above. Now the government supports farmers with direct financial assistance—as President Trump apparently will with his $12 billion relief package for soybean farmers

“In the early ‘90s, and by the mid-‘90s, we had, at that time, record prices for a lot of the grains,” says Glauber. “Because of farm legislation that culminated in 1996, we got rid of the programs that we used to purchase commodities, and converted our programs to income support programs,” like crop insurance, and price and income support programs.

As a result, soybean growers haven’t had to worry about stashing enormous surpluses, says Nancy Johnson, executive director of the North Dakota Soy Growers Association, which represents the country’s sixth-largest soy-producing state. That’s been the case since 1999, when negotiations to admit China into the World Trade Organization (WTO) were underway.

“It’s been a relatively stable marketplace, because China came in, and rules were set up for trading, and trading began, and that became a norm,” Johnson says. “It’s been 20 years of relative status quo.”

It won’t go to crushers (who do exactly what it sounds like). Johnson says that’s because biodiesel plants are already running at capacity. Biodiesel is a “24-month deal,” she says, which means that growers don’t have the chance to sell their soy again until the 2020 harvest. Plus, she says, “very little soybean oil” actually ends up being made into cooking oil—only about 5 percent of the total soybean crop, according to Mark Ash, a USDA economist.

Maybe it’ll just stay on the farm.

“We often have a stock of soybeans greater than the demand at any given time,” Johnson points out. Generally speaking, she says, farmers store their soy surpluses for a season, before making room for the next crop. But even that normal tactic of holding onto the grain, and waiting to sell whatever’s left before the next round of planting, is becoming more expensive. Due to steel tariffs, Johnson says, the cost of grain bins—corrugated steel cylinders that hold up to 200,000 bushels—in North Dakota had risen by 20 percent “since the day after the first tariff was announced.”

“Argentina has already bought some for the fall,” says Glauber. In the past, that’d be highly unusual for a country that is itself a major soy grower. But times have changed, and so have prices. Argentina is taking advantage of the fact that soybeans in nearby Brazil, for example, are far more expensive than U.S. soybeans. “U.S. soybeans are cheap in the world market, so people will buy them.”

And when U.S. prices are low, price support programs kick in. While that’s normal, and up-or-down swings of 250 million bushels aren’t out of the ordinary—think of a bumper crop—Glauber contends there’s a much bigger problem on the horizon. American soy production has basically been rising in concert with Chinese demand. If our ability to meet that demand continues to be hamstrung by an ongoing trade war, and American growers have to find new buyers not just for now, but for seasons to come, prices will stay low.

And that would make this year’s all-time high of acreage planted a peak—not a step.