Suzanne Kreiter/The Boston Globe via Getty Images

When employees at three Starbucks locations in Buffalo, New York, announced their intent to unionize this August, followed shortly after by two additional stores nearby, they had reasons for optimism, even if none of the nearly 9,000 company-owned stores nationwide are currently represented by a union.

Before going public with their campaign, the employees made inroads with Workers United, the union that had helped successfully organize local coffee chains SPoT and Gimme! Coffee in upstate New York well before the pandemic. Those efforts resulted in contracts that guaranteed wage increases, paid sick time, and protection from unfair firing. Elsewhere, employees at Colectivo Coffee narrowly won representation this August for roughly 400 colleagues at the chain’s Wisconsin and Chicago locations, following a long and drawn-out campaign that workers accused management of attempting to upend. And that success came on the heels of voluntary recognition for the eight-unit coffee chain Pavement in Massachusetts, which organized in June with UNITE HERE’s New England Joint Board.

The Starbucks union drive is riding this broader wave of labor activism sweeping coffee shops, along with the nation at large. But given how historically difficult the food-service industry has been to unionize, what can coffee shops teach us about what works? Also: Why now?

Food service and drinking places, a broad categorization by the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) encompassing sit-down restaurants, fast-food chains, caterers, bars, and more, have a fairly dismal record when it comes to successful union campaigns. The challenges are many: Turnover is high and employment is often seen as temporary, giving workers little reason to invest time and energy into a campaign whose benefits they might never reap; divisions between front- and back-of-house staff are commonplace, particularly regarding wages; and a 2020 National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) ruling made it difficult for fast-food companies to be held liable for labor violations at franchisee locations, thereby limiting the gains employees could make by organizing. While unions once represented broad swaths of the food-service industry—nearly a quarter of female servers in the mid-20th century, for example—today the sector ranks among the least unionized, according to BLS.

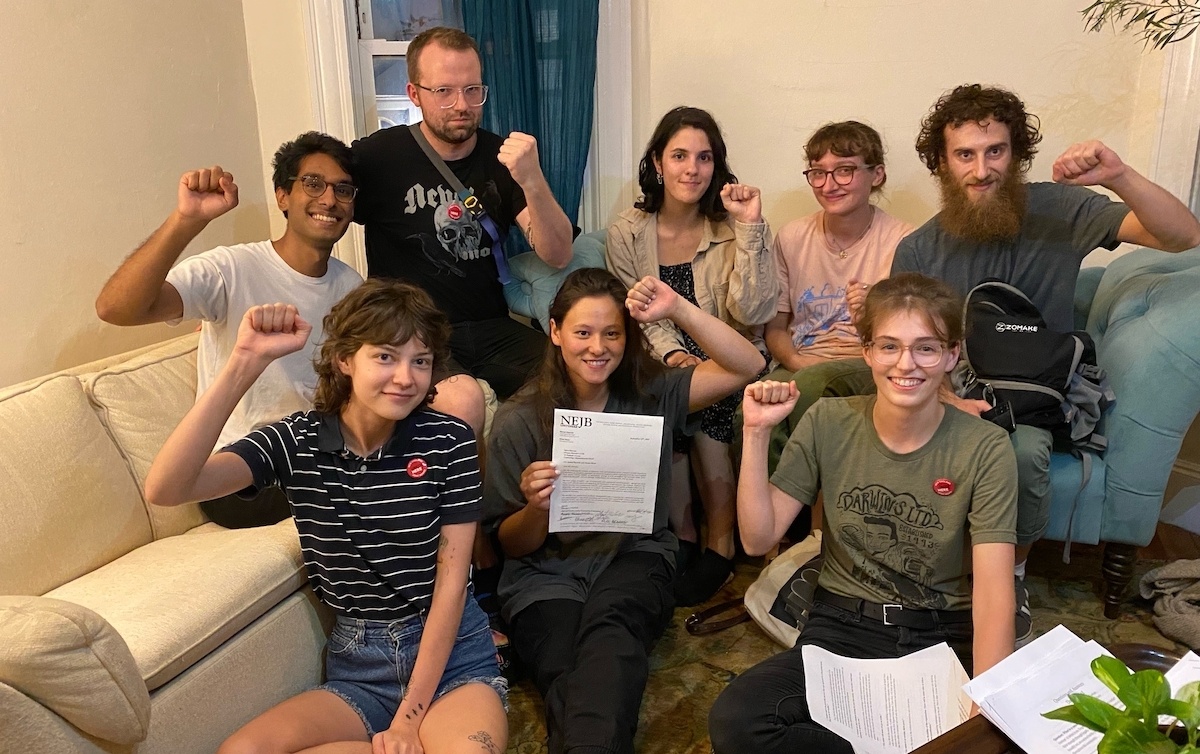

Workers of Darwin’s Ltd. gathered to sign organizing letters. The four-unit coffee shop chain is in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

New England Joint Board UNITE HERE

Yet in one small corner of the food service and drinking places sector, cafes and coffee shops have recently emerged as a bright spot for unionism. Beginning with Gimme! Coffee in 2017, employees have successfully voted to organize at multiple shops in at least a half-dozen regional chains as well as a handful of independent units. The reasons motivating coffee shop workers to unionize are not dissimilar from problems elsewhere in food service—among them low wages, difficult scheduling, and a challenging work environment, all of which have been exacerbated by the pandemic—but the reasons for their success are in many cases distinct.

If there were a recipe for ideal organizing conditions, it might look something like this:

1. One cup appealing, well-marketed company values

To start, coffee shops often function as a dedicated “third space” in their communities (think open-mic nights, group meet-ups for retirees, game-players, and activists, and college students studying together for exams). Additionally, coffee shops serve as a symbol for independent business boosters who prefer to vote with their dollars. As such, many companies have realized that doing “good”—a vague patchwork of values that conveys the overall idea that no one was harmed (and some might have benefited!) in getting you this cup of coffee—is crucial to the bottom line.

Coffee shops that make their values visible to customers are also highly attractive to a certain type of employee—in particular, the type who might be amenable to organizing. While attending college, Hillary Laskonis, a barista at Colectivo in Milwaukee, regularly studied for her classes at one of the chain’s locations. “I took a break from school,” she said, “and it was one of the first places I thought to apply because of the progressive values.” But some workers have learned that even if their employer positions itself as a champion of worker equity and well-being, that doesn’t mean it will uphold these principles when employees attempt to organize.

“The pandemic added a sense of urgency. It got people talking to one another and realizing how much we have in common and how much we agree on the solutions.”

“I wanted to work [at Starbucks] because of the progressive values that they hold,” Casey Moore, a Starbucks barista, said, citing the company’s support of Black Lives Matter and LGBTQ advocacy. Using Starbucks’s term for its employees, Moore added, “I think even just showing that they actually are pro-partner like they say they are, by respecting our right to organize, would be a huge symbol of them actually living up to those values.”

Employees at all the companies I talked to for this story shared similar complaints: Management that prioritizes customer satisfaction over workers’ sense of safety and defective equipment that makes completing daily tasks difficult, if not dangerous. Scheduling difficulties seemed to be near-universal, and as a result, a number of them said they have struggled to hold down a much-needed second job.

The pandemic further inflamed these problems, while introducing new challenges for employees, which ranged from having to enforce mask-mandates to navigating the chaos of chronic understaffing and supply chain shortages at their stores—all while risking their own health and safety to serve a public that doesn’t universally adhere to store safety policies.

It wasn’t too far into the pandemic before workers in such jobs arrived at the same conclusion: A union could at least give them a voice and platform through which they could address their grievances. “The pandemic added a sense of urgency,” said Kait Dessoffy, a Colectivo shift lead in Chicago. “It got people talking to one another and realizing how much we have in common and how much we agree on the solutions.”

2. One handful particular employee demographics

Another reason coffee shops seem especially successful when it comes to organizing: their workers tend to skew younger compared to the median age of the workforce. Zippia, a job search site, reports that the average age of baristas is 27.9 years, which according to a recent survey by Pew Research Center, falls into the age group (18-29 years old) most in favor of unions (69 percent). This, despite union membership rates having declined from 20.1 percent in 1983 to 10.8 percent last year.

Ruth Milkman, a labor sociologist at the City University of New York Graduate Center, said that many of the workers currently organizing are young—a number of them are under 30—but also college-educated and underemployed. “I suspect they’re more persistent in trying to make it happen than someone who’s supporting a family on the minimum wage and doesn’t have a lot of job options beyond what they’re doing at the moment,” she said.

Annina Kennedy-Yoon, a self-identified Generation Z barista and member of the organizing committee at the four-unit chain Darwin’s Ltd. in Cambridge, Massachusetts, recounted complaining with her friends and co-workers that she probably will “work until I die to just barely afford an apartment,” adding, “I think a lot of younger people are realizing that and saying, ‘No, I don’t want to do that anymore.’”

Massachusetts State Representative, Mike Connolly, center, with workers from Darwin Ltd.

New England Joint Board UNITE HERE

Disillusionment about the future, coupled with the feeling of being let down by an employer you’d hoped was going to lead with its values, can be powerful catalysts for organizing. Bryant Simon, a professor of history at Temple University and author of “Everything but the Coffee: Learning about America from Starbucks,” interviewed a number of Starbucks employees for a 2008 study about the struggles that accompany working for the coffee behemoth. Often his subjects complained that a significant chunk of their already low pay went toward covering the costs of their part-time employee health benefits—a perk Starbucks has regularly held up as evidence that it cares for its employees—and also that the scheduling system made life difficult.

Employees like Moore, who come to work at a company like Starbucks on the promises of a pro-worker setting and alignment with their principles, might never have considered a union before, Simon said. But even with all its branding as a bastion of good-for-people-and-planet values, Starbucks is still a corporation, and it will behave like one. “That involves extracting the most value out of labor, and I think that galvanizes some people,” he said. “They came believing some of the promises that Starbucks makes, and when they’re disappointed, that’s how people get radicalized, right?”

The first time an idealistic worker collides head-on with a bottom-line-driven company can be dispiriting—and also highly motivating. “The beaten-down worker is not the most dangerous one” for companies concerned about employee organizing, Simon said. “It’s the one who is disappointed” that’s most likely to change things.

3. Two scoops relationship-building spaces

Also key to successful organizing is a physical space that encourages workers to build solidarity. Eli Wilson, a sociology professor at the University of New Mexico and author of Front of the House, Back of the House: Race and Inequality in the Lives of Restaurant Workers, explained that this is a particular challenge at restaurants, where structures both concrete and intangible divide workers. Of course, there are literal barriers dividing a restaurant’s dining room and its kitchen. But Wilson, who worked in restaurants in Los Angeles to conduct research for his book, also mentioned ingrained differences in the racial demographics of those typically hired for jobs in the back versus those who get hired to work up front, taking customers’ orders. And restricting tip pools only to the front-of-house staff, which has long enabled servers and bartenders to vastly outearn their back-of-house colleagues, can further exacerbate tensions. “What is so dangerous about some restaurants is that oftentimes the ‘we’ is only superficial and it’s really an ‘us versus them,’” Wilson said. “I think in many coffee shops, we simply don’t see that kind of segmented division.”

“What is so dangerous about some restaurants is that oftentimes the ‘we’ is only superficial and it’s really an ‘us versus them.’ I think in many coffee shops, we simply don’t see that kind of segmented division.”

Indeed, many baristas I spoke to described the shared dread of taking and filling drink orders in tight spaces during morning rush hour as one of many bonding experiences. And some employees who recently unionized pointed out that, even in coffee shops that do have a kitchen in back, worker divisions were often negligible. Zach Anderson, a kitchen manager at SPoT, said that baristas and kitchen staff at the cafes are usually not fixed positions and that wages for non-managerial employees are all the same, with tips distributed evenly regardless of a person’s station. “In situations where you’re dealing with long lines on the busiest weekend days and tickets in the kitchen and on the barista station are congested, all of us feel food rushes and feel being overworked and understaffed,” he said. “Misery breeds company.”

4. Three gallons community support

Being located in hyperliberal college or historically pro-labor communities—or in some cases, both—has also been a boon for workers in the middle of a union drive. Laskonis, whose father is an IBEW organizer, said that a number of her co-workers could remember the Act 10 protests of 2011, when tens of thousands of people flooded the state capitol in Madison for weeks to rally against legislation that weakened public service employees’ collective bargaining rights. During the Colectivo union drive, one of Laskonis’s favorite customers turned out to have a labor background and regularly stopped by with friends who were active or retired union organizers. In Buffalo, hundreds of people turned up for rallies supporting the SPoT union, and New York’s Democratic State Senator Tim Kennedy urged customers to boycott SPoT after the company allegedly fired three employees for organizing. And workers at Darwin’s Ltd. saw any opposition to the union drive by their employer, which has long sold itself as a community-focused hub in a solidly left college town, as self-sabotage.

“It would look so bad if they tried to do any kind of retaliation or any kind of union busting here because we had state representatives doing photo ops [and] we had multiple city councilors retweeting us,” said Eleanor McCartney, a shift manager at Darwin’s and a member of the organizing committee. “It is so much like liberal peacocking. That’s what people care about here, like how liberal can you be?”

That’s not to say companies, big or small, won’t try to crush budding unions. Colectivo affirmed in a letter published by the local news outlet Urban Milwaukee its support and care for its workers. But in the year leading up to the NLRB vote, the company hired consultants who, according to workers, attempted to deter them from joining a union through “captive audience” meetings; as was the case with SPoT, Colectivo workers I spoke with told me they strongly believed that management had fired or let go of workers for organizing. When I reached for out for comment, a PR representative for Colectivo responded with a copy of a letter it had sent to workers during the union drive, which encouraged them to support the company by voting no on a union. She also forwarded the company’s public response to election outcomes in August.

Starbucks continues to brand itself a pro-worker business. And with much deeper pockets than many small independent chains, it also has more resources at its disposal—be it to cover the costs of consultants or the financial penalties for what the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) has found on several occasions to be an illegal effort to fire workers for organizing.

For the Buffalo drive, the company has hired Littler Mendelson, which describes itself on its website as “the largest law practice in the world exclusively devoted to representing management in employment, employee benefits, and labor law matters.” It also parachuted in corporate officials and managers from other states to Buffalo, which employees documented in a photo posted to Twitter. Higher-ups have since held “listening sessions” to discuss workplace complaints, which workers said carried an anti-union tone, and routinely made their presence known via store visits. Reggie Borges, a Starbucks spokesman, told me that these visits and meetings are standard practice to address complaints and concerns, and that company leaders have held about 2,000 listening sessions this past year.

Earlier this month, it was reported that the coffee chain temporarily shuttered two of the five Buffalo stores that had filed petitions for union elections. (Of the five stores, two had withdrawn their petitions to help speed up the unionization process.) The company has said the temporary closures were unrelated to workers’ organizing efforts.

On Wednesday, the company announced that it will raise its minimum wage nationwide to $15 an hour next summer, which Borges said is also unrelated to the union drive. “Back in December of 2020, Kevin [Johnson, president and C.E.O of Starbucks] went on the record saying we have a goal of reaching $15 an hour by 2023,” Borges said. “This is in line with the commitments we had made.”

Yet even in the face of an increasingly uphill union drive, Starbucks employees say the company’s resistance is reason to continue their fight—and, they hope, inspires others to do the same. If a drive can be successful in a nearly 9,000-store chain, the thinking goes, perhaps indie coffee shops won’t prove to be outliers for much longer.

“People believe in this and we want it to happen,” Moore, the Starbucks barista, said. “We’re not giving up because Starbucks wants us to vote no.”