Photo by Libby Anderson/Flickr/Nicolas Raymond/Graphic by Talia Moore

A weekly series about one chef who closed three restaurants during the pandemic—and intends to get them back.

Gavin Kaysen used to be a chef, restaurant owner, husband, dad, and sports fan.

Now Gavin Kaysen is an activist, the founder of a nonprofit, a consultant to floundering purveyors looking for new income streams, father figure to employees past and present, sanitation engineer, landlord-tenant negotiator, community liaison, and owner of two brand-new take-out operations. And, still, a chef, restaurant owner, husband, dad, and sports fan.

“Closed” may sound definitive—how much can happen if nothing’s happening?—and yet Kaysen’s life is more of a whirlwind than ever. A man who prized his privacy has joined the public chorus of independent chefs and restaurateurs demanding that small businesses get a fair share of aid, and not be shut out in favor of corporate chain operators. A chef who used to be surrounded by a team of precision cooks now makes pasta with his eight-year-old son, surrounded by emptiness.

A new array of demands competes for his attention, in no particular order and often by surprise. His initial appraisal of the Covid-19 time warp—no 10 minutes are the same as the 10 that preceded them—continues to define daily life. Yes, the government announced a stimulus package, but no, it wasn’t clear, at first, if independent restaurants would get the helping hand they’d been lobbying for.

They wouldn’t, but there was no time for disappointment.

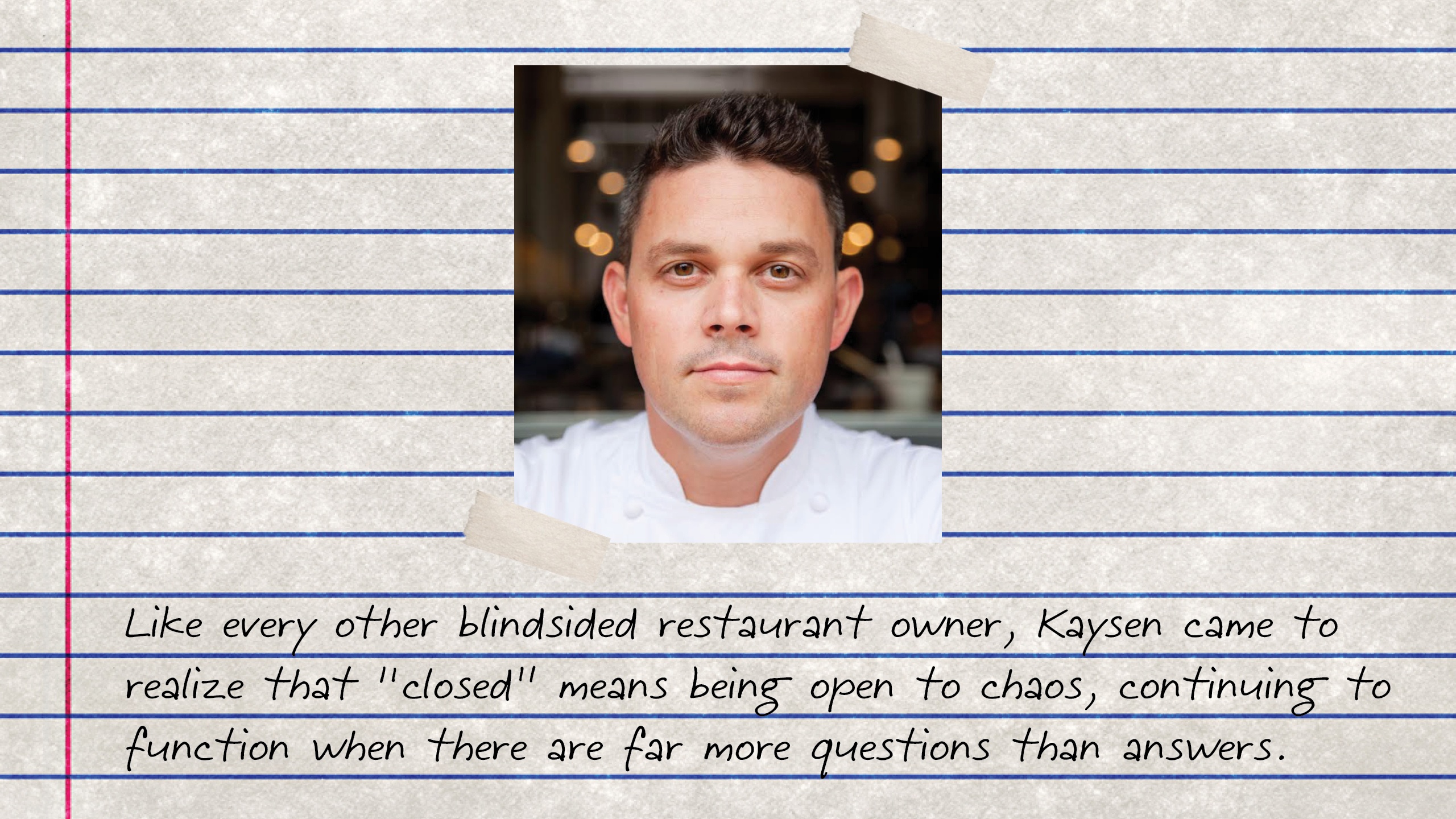

His modulated life is out the window, but, like someone deciding what to grab when the house is on fire, Kaysen tries to figure out what to salvage from the past to survive the future. The week was a nonstop juggle: like every other blindsided restaurant owner, he came to realize that “closed” means being open to chaos, continuing to function when there are far more questions than answers.

Kaysen turned for sustenance to small things, kitchen rituals and grandmother memories. He thought about Superman. And then he moved on.

—

Kevin J. Miyazaki/Redux Pictures/Flickr/Nicolas Raymond/Graphic by Talia Moore

The personal is political

I told a friend who’s been in the world of politics, I’ve never been a political type, I reserve my opinions for people I’m close to. Two weeks ago, to be honest, I never thought I’d be in this position. I’ve never been a part of the bigger voice on why things are done the way they’re done, and I don’t want to be the face of what this looks like. But I realized in the last week that there are opinions and voices that matter. If you can stand up and put your voice forward then you’re contributing to the greater good.

And I know we’re fighting for something bigger. The sales tax deferment was something small, on one level, but it was a big win because it established a precedent. Other people can talk about it in their states.

At one point a couple of weeks ago a majority of the people in the profession stopped and said, We have to have one voice now, and I thought, We need to move forward with one voice, how’s that going to happen? And then, boom, there was the email about the Independent Restaurant Coalition and its Save Local Restaurants campaign. It was built so fast, it’s pretty remarkable: there’s a lot of structure, a PR company, an executive director, they got funding, and we get daily updates on how we can help.

Chefs have always been their voice, the farmers and purveyors.

A whole educational process has to happen, and the biggest part of this is to help remind people, give them the quick facts, explain why restaurants need that relief, now, and what it means. The daily updates allow us to go to local officials and say, Listen, this is what we’re getting behind and why. Social media can only do so much. We need to be able to get them facts so they can do things.

The language in the stimulus package is not specific enough for us to understand if it applies to us, to independent restaurants. I’m still trying to sift through it all and learn how do we qualify, what are the ramifications, how do we come back from this, and what does that look like?

But think about the fabric of restaurants in a community. Danny Meyer said something really powerful: The antidote to 9/11 was bringing people together in our restaurants, and now we can’t do that. It was a really relevant piece of information, because people are trying to compare this to something that happened before, and you can’t. We’ve never seen anything like this.

How else can we give back to our community, though? That’s what we’ve been programmed to do.

And I thought, this is the kryptonite. Covid-19 has taken away our strength, that opportunity to bring people together. We weave threads by bringing people together every night, and now we can’t.

—

Kevin J. Miyazaki/Redux Pictures/Flickr/Nicolas Raymond/Graphic by Talia Moore

Open for business

We’re doing take-out at Spoon and Stable and Bellecour, and the first week was great, it produced enough volume to decide it’s a valuable resource to keep going.

We have an entire sanitation system set up. When you come to work, you walk directly into a restroom and change out of the clothes you walked in with, change into work clothes that have been sanitized, sanitize your phone, everything. You don’t just walk in and go to work.

It’s curbside pick-up. The first couple of days we brought food out to cars, but now we go outside, put the order on a table, the customer gets out of the car, grabs the order and leaves.

We have two people in each kitchen, three in the dining room on the phone or computer. On the 23rd we had a zoom meeting—that’s new for me—and I asked if they want to keep doing it, because if they don’t feel safe we won’t do it anymore. They said let’s keep going, but we’ll keep having meetings; we had another two days later to talk about how it’s going.

There’s a side to take-out that I didn’t anticipate, that I’m pleased about. Being able to come to Spoon and Stable or Bellecour to pick up food gives customers a little bit of normalcy, for a moment. I got a message from a woman who wanted to order from Spoon and Stable because it was her husband’s 40th birthday. She said we love the restaurant, he’s just gutted we can’t celebrate inside. So we made a card, and all of us signed it and tucked it into their bag.

It gave us a moment of normalcy, too.

—

Libby Anderson/Flickr/Nicolas Raymond/Graphic by Talia Moore

Bills

A restaurant is an ecosystem. We have paid a handful of our vendors, doing it slower than normal, but I am trying to honor that as much as I can. I don’t think it is fair for us to leave them in the dark, and with some of them we’re going to try to figure out, in the next couple of days, how they can diversify their businesses. Maybe the U.S. Foods of the world can handle no payments for a little longer, but someone like Peterson Craftsman Meats in Wisconsin I don’t think can.

As an example, we have a fish purveyor, Fish Guys, and I was just talking to the owner, Tim, about how much he has in receivables that will likely not be paid. But they have an opportunity, and I think they’re going to do this, to sell via FedEx to people’s homes. There’s Farmer Lee Jones from The Chef’s Garden, or Keith Martin from Elysian Fields Farm—great lamb—so can we cook their food and also say, Go buy this fish or butter or lamb and get it delivered to your house? I saw Cory Lee from San Francisco’s Benu, on Instagram, talking about how important it is to support our vendors. We’re going to try to figure it out in the next couple of days. Chefs have always been their voice, the farmers and purveyors.

If people are going to buy from Instacart, can we find a way to help them buy from the guys at Peterson, in Wisconsin? You’re taking care of a local farmer who’s part of our fabric, our community.

We are hospitality people, and we always want to give back. This is our opportunity to turn it around and say we are asking you to help.

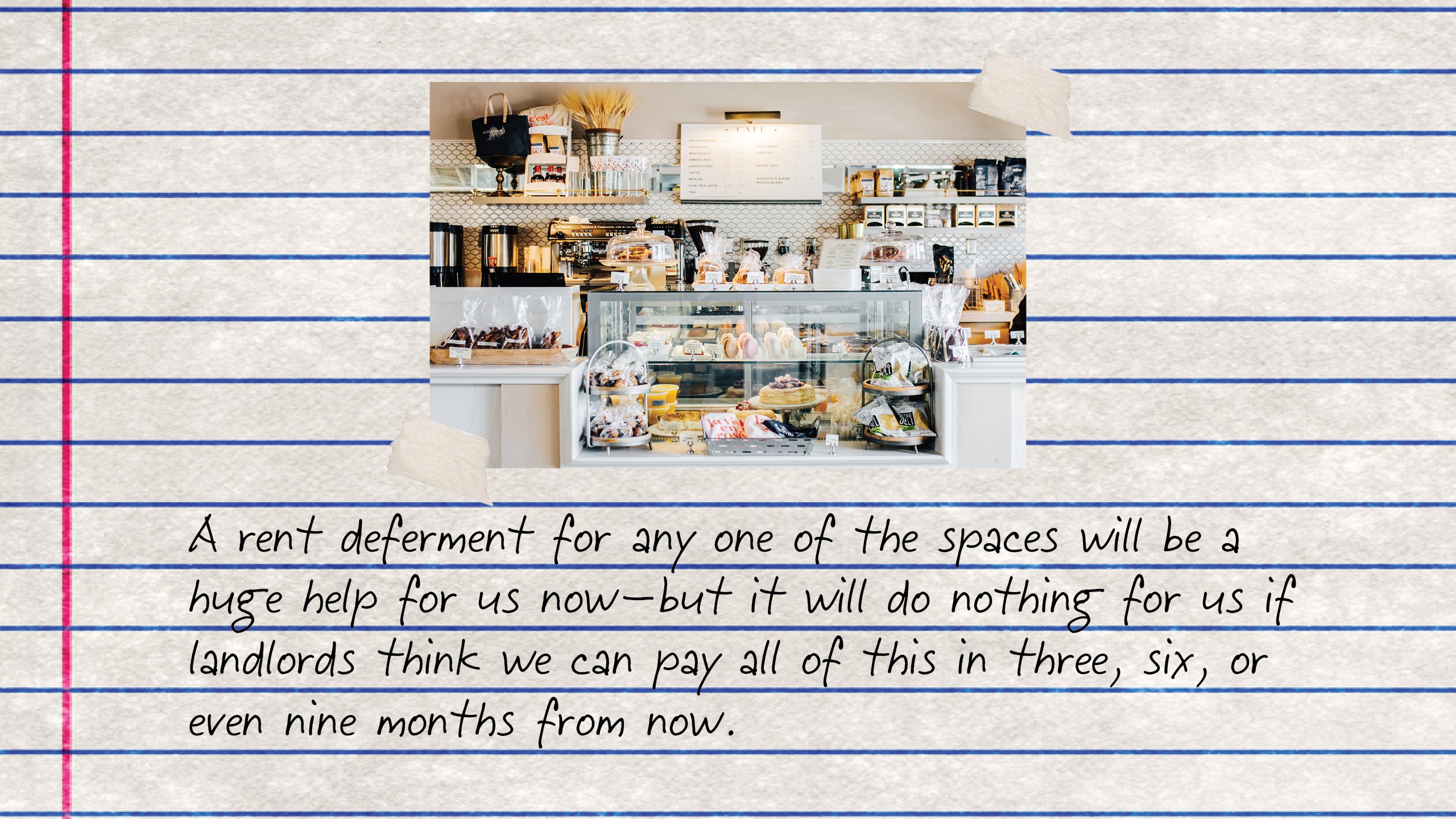

And then there’s rent. I rent all three of my buildings. Two of the landlords have been understanding and offered us a deferment of the April rent, and we’ll talk again in mid-April to determine what needs to be done in May. From there we will have a conversation on how to handle this best, because this is of course subject to their lenders, the banks, and the federal government. We’re really in a holding pattern for the time being.

I have good rent deals in all the restaurants, Spoon and Stable is the highest, north of $150,000 per year, but it’s not the rent as much as it is a combination of storage, taxes and other charges. A rent deferment for any one of the spaces will be a huge help for us now—but it will do nothing for us if landlords think we can pay all of this in three, six, or even nine months from now.

One landlord has been less accepting of the situation, but we are still not going to pay the rent as he would like it, for now, because there is more for us to get through. There should not be a power struggle between tenant and landlords right now; we are all in this to find ways to make it work, and working with each other is the only way to do that.

I will say that crisis brings out the best and the worst in some.

—

Kevin J. Miyazaki/Redux Pictures/Flickr/Nicolas Raymond/Graphic by Talia Moore

The restaurant family

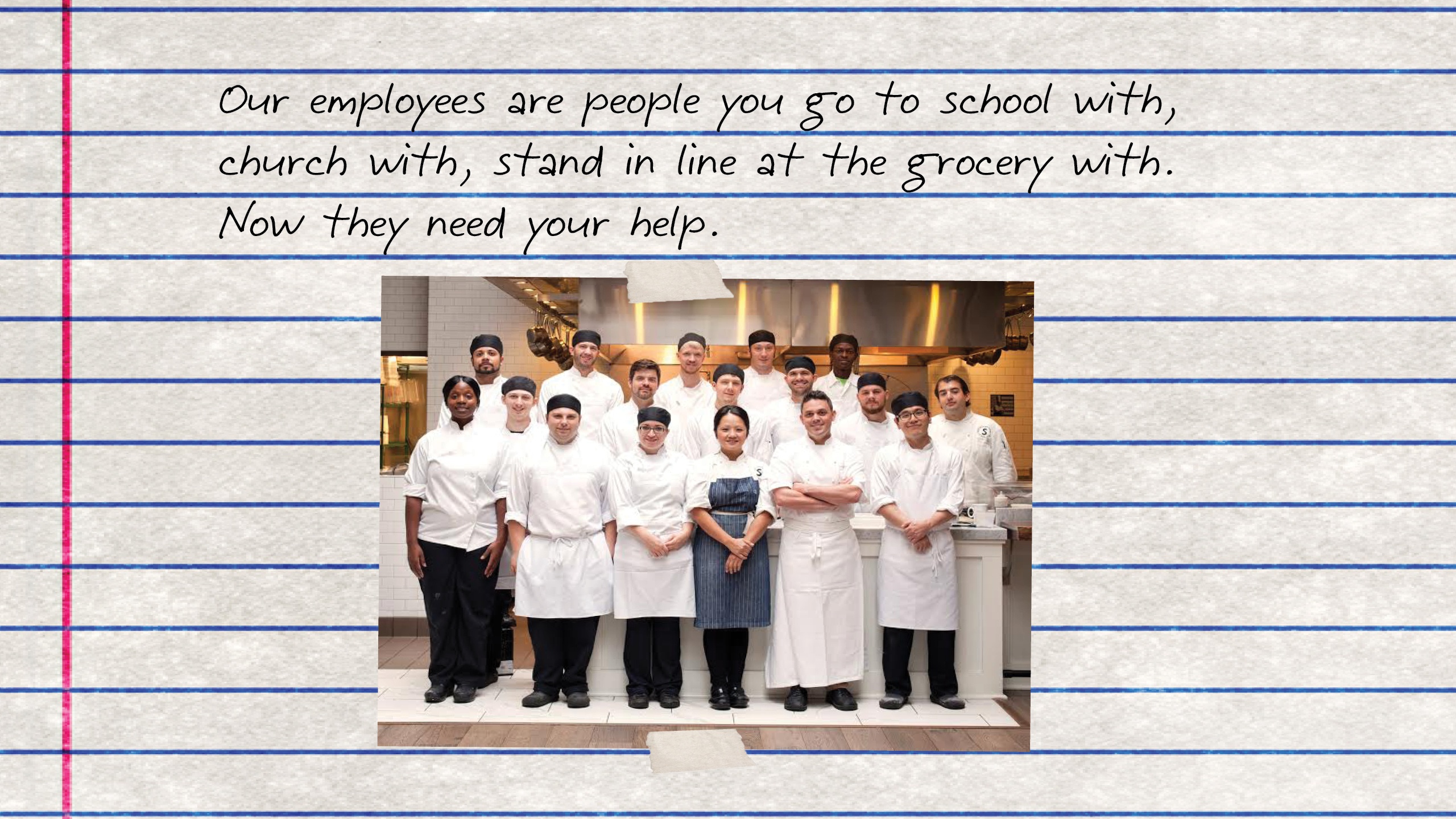

The irony is that for some time Alison, our director of development, and I have talked about creating a nonprofit in our group, and suddenly we had an immediate need to help our team, 180 furloughed employees. So we formed Heart of the House Foundation and put together a board of directors, I’m not on it, and applications went out March 24 and were due March 30. Annah, my assistant, called people who don’t have email to make sure they know they can apply for this, and one person she talked to today was in tears, just saying thank you, over and over.

My wife and I made an initial donation of $10,000. And the first three donors we had today were people who were furloughed last week, which shows you how important it is to them that their co-workers can bridge the gap. People can ask for a certain amount, and give us an explanation of what else they might need. As of three hours ago we had thousands and thousands of dollars after that initial donation, so we’re going to grant as quickly as we can.

We are hospitality people, and we always want to give back. This is our opportunity to turn it around and say to people who’ve celebrated with us on that birthday, that anniversary, anything, to say, We are asking you to help. Our employees are people you go to school with, church with, stand in line at the grocery with. Now they need your help.

And when we say we need help, we are not asking for you just to give us money. We are asking for you to put us back to work.

So this is something I can do locally, to look after as many employees as I can and get the community involved. One employee’s dad, who lives 500 miles away, posted on Instagram that he had “skin in this game” because his daughter was part of our restaurant family, and said we’d “taken a weight off this father’s shoulders.” He plans to drive in when we re-open.

—

Generations

There are so many questions to answer beyond the restaurants. With my older son, who’s 10, talking helps you simplify what’s happening, not simplify, but you break it down. He said, “I’m so scared you’ll get sick, I’ll get sick, what happens if you die?” And then I have to say, Wait, we have to look at this. I’m okay, you’re okay, take it down, we’re a healthy family and we’re doing all the right things we are supposed to do.

My eight-year-old doesn’t seem to care as much about it. I put a video up on Instagram, we were at Spoon and Stable and he was hungry so we decided to make pasta. We’ve got some fresh pasta, the water’s almost ready, some butter in a pan, and he’s got his plate. I looked up, at that big empty space, and said, “and a very empty restaurant.”

He turned around to look at it and then looked at me. “Because it’s closed,” he said. “Because of the coronavirus.”

“Shit,” I said.

“Yeah,” he said. “Shit.”

When I was his age, I’d be in the kitchen with my grandmother, she was a great cook, a great baker, and she used to tell me, “There’s only one thing you’re allowed to say if you mess something up in my kitchen, and that’s ‘shit.’” She used to say she wanted her tombstone to say, “I always had fun and it was okay to say ‘shit.’” And her tombstone does say, “She had fun,” but we couldn’t quite tell the world her favorite word was ‘shit.’ So I will. The situation we are in right now is shit.

—

Kevin J. Miyazaki/Redux Pictures/Flickr/Nicolas Raymond/Graphic by Talia Moore

Taking stock

I don’t have enough time to think. I usually take a lot of time for reflection, I write things down, so I dedicated tonight to creating that headspace for myself. To sit in a quiet space at Spoon and Stable and set aside time to be alone. I usually do that at some point during the week, alone time to create reflection, but I haven’t done it in three weeks. I really need it.

It’s like you stop going to the gym and then at some point you think, No, I have to go to the gym. So I’m going to try to do it.

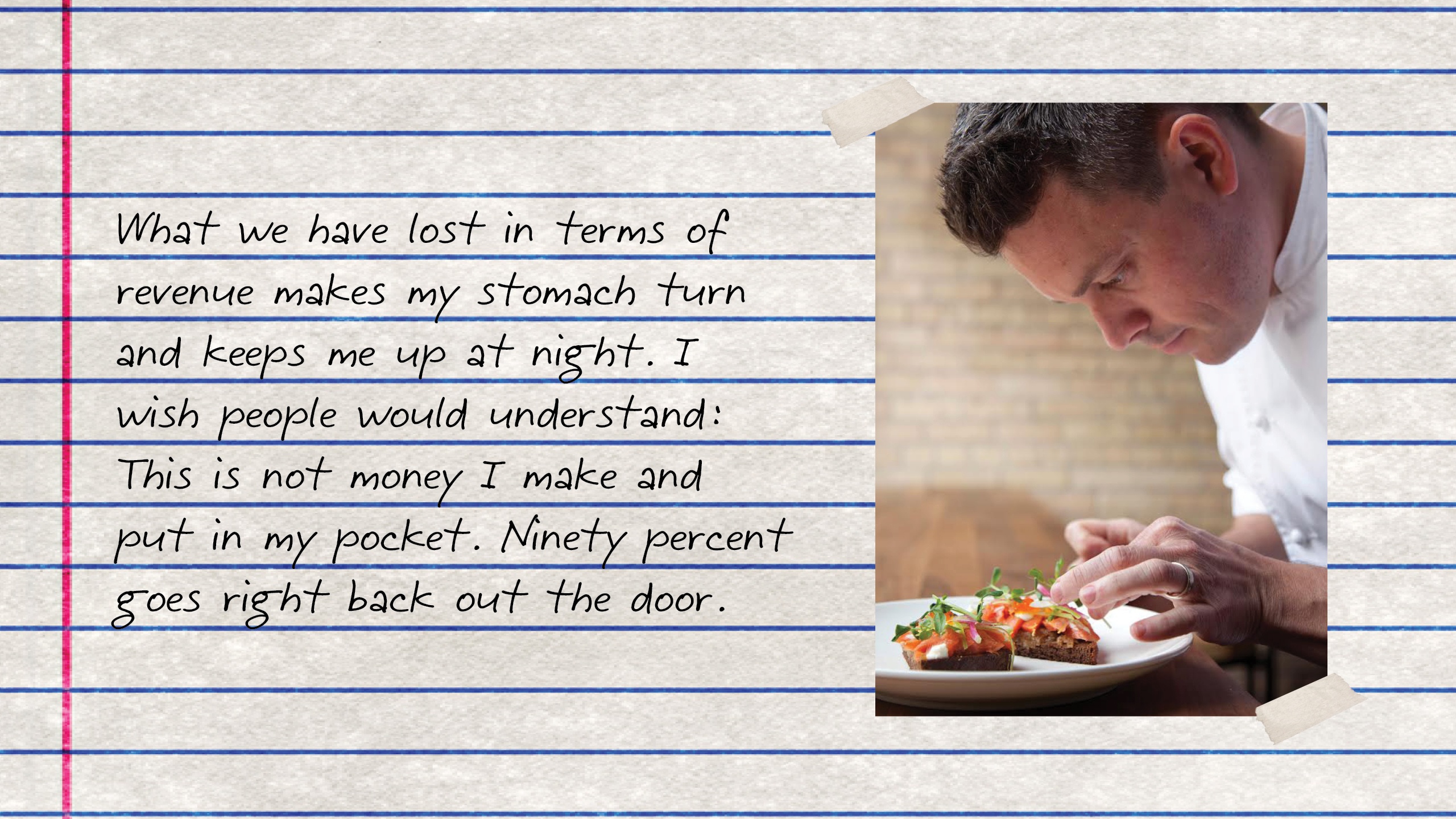

What we have lost in terms of revenue during this time is more than I want to say, but enough that makes my stomach turn and keeps me up at night. I wish people would understand: This is not money I make and put in my pocket. Ninety percent of what we make, as restaurants, goes right back out the door. It pays for payrolls, taxes, rent, vendors, farmers, liquor licenses, food licenses, and more. The expenses are enormous.

—

Meditation

Our pastry chef, Diane Moua, posted a video on Instagram of me folding kitchen towels. Everyone who’s worked with me knows that when I start to fold towels or clean I have a lot on my mind. That’s how I make the time I need to think through things. I heard from a mentee of mind, a cook in his twenties in San Diego, who texted me when he saw that post: “I think there’s a whole generation of chefs who fold towels the way you do.”