Photo by Libby Anderson/Flickr/Nicolas Raymond/Graphic by Talia Moore

A weekly series about one chef who closed three restaurants during the pandemic—and intends to get them back.

A successful television series—which we all have too much time for at the moment—ends each episode with a cliffhanger, the unresolved moment that lures viewers back the following week. Will the heroine lose her job, will the hero find true love, and what happens when the medical tests come back?

But cliffhangers require a counter-balance if they’re going to work; the viewer tunes in again anticipating the same characters facing the same predicaments in the same setting. That’s what’s missing, now: we can’t make out the distant shore. Chef and restaurateur Gavin Kaysen hears predictions about when restaurants might re-open and how they might look, and he tries to shape his own vision of what’s next, but nobody knows what the future looks like or when we will get there.

What we know best is the scope of what we don’t know, which, like the disease, seems to increase exponentially. One thing is sure: Next week’s episode will take place in an altered reality, which is what makes it scary, rather than an edge-of-the-seat thrill.

Gavin Kaysen writes behind the bar at Spoon and Stable. He has come to a resolution to stop guessing what will come next because the future is out of his control.

Dave Puente

As our initial shock gives way to gloves and disinfectant wipes and masks that look as familiar as sweatpants, Kaysen monitors the present, even as he ponders what next season might look like and when it will debut.

When Soigne Hospitality opened Spoon and Stable, just over five years ago, Kaysen and development director Alison Arth created an annual daylong conference for employees called Development Day, which grew from initial conversations about restaurant life to address everything from addiction to financial planning. The one scheduled for the day after Memorial Day this year has been postponed until who knows when. “We don’t do big thinking when we’re in survival mode,” said Arth.

So Kaysen toggles between the apocalyptic and the mundane as he tries to figure out what to do. One minute he wonders if his youngest restaurant will come back at all; the next, if he can tweak his meatball recipe to make his younger son more willing to eat them.

—

Dave Puente/Nicolas Raymond/Flickr/Graphic by Talia Moore

Out of control

It’s hard to say what comes next. I’m talking to people in New York who are thinking they’ll be open in September, people in Chicago say August, but then there’s the whole other side: How’s the supply chain doing, and how does that kick back into gear? At one point I said we’d probably be open July first, but if they’re saying August and September, we could be later.

I’ve come to a resolution: Stop guessing. It’s not in my control, it’s not something we can know right now. I’m a control freak, and so I want an answer, but that’s not going to happen.

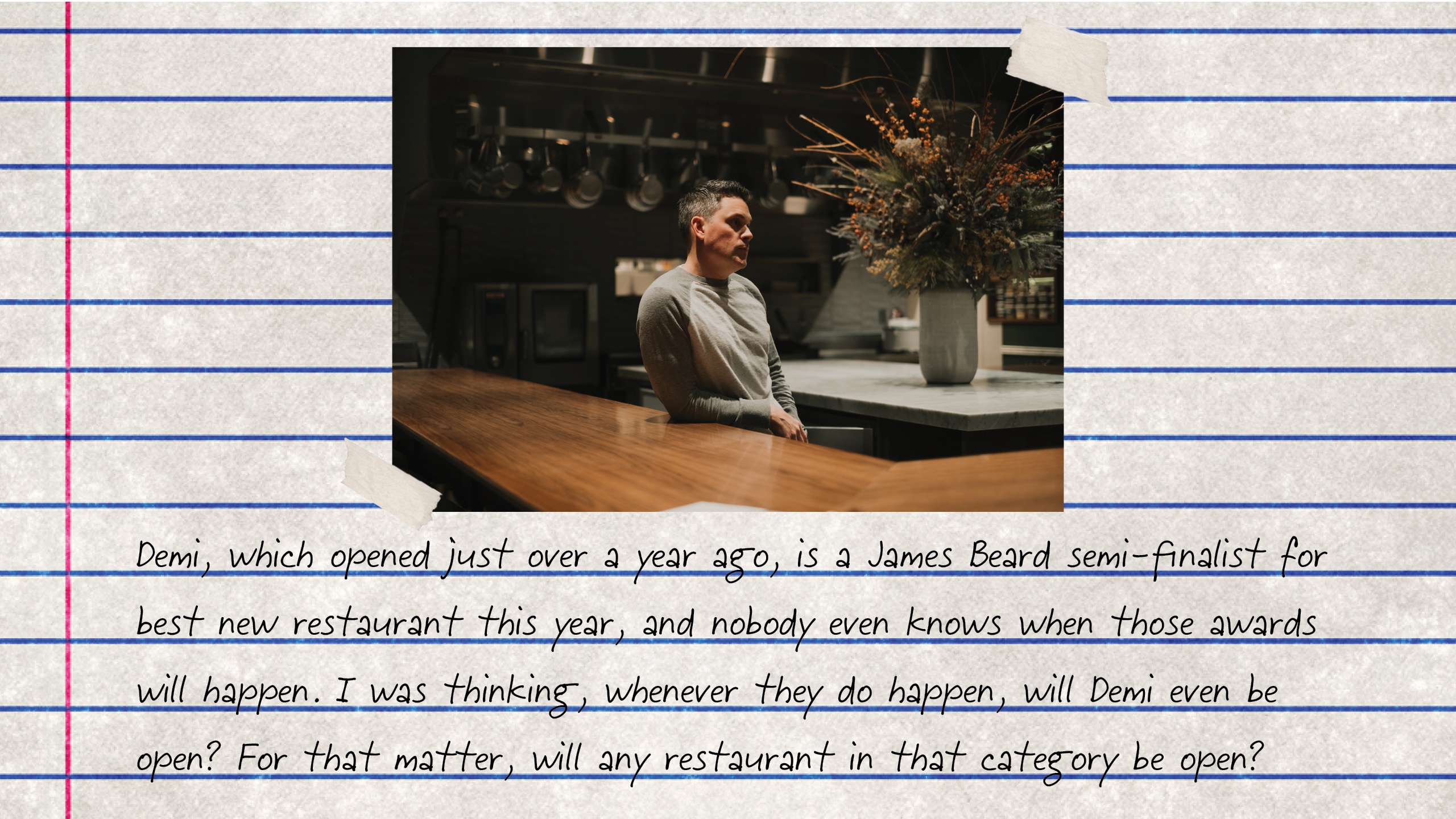

Demi, which opened just over a year ago, is a James Beard semi-finalist for best new restaurant this year, and nobody even knows when those awards will happen, because they’re not happening in May. I was thinking, whenever they do happen, will Demi even be open? For that matter, will any restaurant in that category be open?

Demi was lucky because it had one year—booked solid for one year—and people are still excited about it, but that restaurant scares me. I’m scared to know what’s going to happen to a restaurant like that, only a year old, 20 seats, the roots aren’t deep enough to hold Demi up. Maybe Spoon and Stable’s and Bellecour’s roots are deep enough to hold Demi up, but what does it all look like, in the end?

Dave Puente/Nicolas Raymond/Flickr/Graphic by Talia Moore

I was at Demi picking up some mail and I turned around and it just broke me. For five seconds I could see it—the people, the noise, the energy—and then it was gone again. At moments like that it’s really raw, so painful, such a punch in the gut. A part of me smiles at first because I can feel the energy. I’ve walked through spaces before, to see if we want to build there, and you get a sense of whether there’s energy or it’s completely dead. I could still walk through Demi and feel the energy.

We’re not giving up, I want to keep up, I want the restaurants to be open and people to be in them—but how do we do it? David Chang has always preached: this idea of what made restaurants survive in the past can’t be the way we go moving forward.

Every day the hill gets a little bit steeper. I’m feeling pretty okay, but no matter how much progress you make, you look up and it’s a little bit steeper. So I’m trying not to look up, not to look for the top of the hill.

—

Dave Puente/Nicolas Raymond/Flickr/Graphic by Talia Moore

The legacy

We’re applying for everything we can apply for, and then we’ll see what the guidelines actually are. There’s this payment protection program, but the thing is, banks have not been given regulations yet, we don’t know what it actually entails, but I have a call with the banks and lawyers today, and we’ll try for any loan that’s out there.

And the insurance thing is a mess. There’s a line item in most everybody’s insurance saying that they don’t cover viruses or outbreaks, so you file a claim, they deny your claim, and then you have to fight for the claim. There’s a group called BIG, Business Interruption Group, chefs Daniel Boulud, Thomas Keller, Wolfgang Puck and Jean-Georges Vongerichten, and their lawyer is going to represent us as well because our insurance got declined.

They had a conversation with President Trump, in fact, I spoke to Thomas and Daniel last night and they’re upbeat and fighting. The entertainment tax deduction got taken away in 2017, but if that gets put back into play when we re-open that would be huge. It will help stimulate the economy faster, it will motivate people to go out and spend x amount of dollars for a business dinner in a restaurant’s private dining room. We lost a lot of money in private dining room business after 2017.

It isn’t until after we re-open, but every rabbit needs a carrot. If we can get there, it’ll make a big difference.

The Paul Bocuse generation, starting in the late 1960s, did something remarkable for us—brought the chef out of the kitchen, allowed the chef to talk to the guest. The next generation, Daniel Boulud and Thomas Keller, opened up restaurants in the rest of the world, gave chefs a passport to the world, to make pâté en croûte in New York City, Singapore, anywhere. So I’ve questioned myself: what is our generation going to do to better serve the next generation? We’re standing in it right now, and, thankfully, we have the previous generation still here to help us carve this out.

It’s a much bigger fight now. They know what the legacy looks like.

—

Dave Puente/Nicolas Raymond/Flickr/Graphic by Talia Moore

Ex-employees

We’ve always tried to do a bunch of work ahead of time in terms of mental health. There was a group-wide email, a lot of operators, chefs, owners in the Twin Cities, what is everyone doing about mental health, how are they responding? And a year ago we asked all our managers to add information to a group document about how they battle through, whether they go for a walk, go to the gym, talk to a friend. It’s a huge google doc that goes to all employees, a real resource, as well as information about what your insurance covers, here’s the co-pay, here’s how you can access resources.

And the Heart of the House Foundation is helping. It’s a little of everything, and we get letters from employees that help us understand where people are: people are struggling to buy diapers and groceries for the day, and we try to provide resources and help.

But I’m at both ends of the spectrum, dealing with the restaurants, dealing with individual employees. There’s so much happening. You don’t always know where to be—you don’t even know where to look.

—

Dave Puente/Nicolas Raymond/Flickr/Graphic by Talia Moore

Silver linings

For the first time in my life I get to read a book to my kids every night; that’s never happened before, it used to be one night a week if I’m lucky, maybe two. Julius likes to write his own comics, so we read a lot of his own books, such an exploration in fun. They’re also both in French class, so Emile is reading me a book in French. And we’re reading the Tom Gates series by Liz Pichon.

I’m pretty good about being home. I’m usually in the restaurants five or six nights a week, but now that the kids are older, and in school, I try to be home two nights every week—usually Saturday and Sunday, because messing up their routine during the week was harder for them. So I’ve just taken Saturday and Sunday, and I go from there.

This is different. Julius asked the other day, “Are you going to be home every night?” like it kind of messes him up. When I make dinner, I will say, ‘You have to try this and that,’ and sometimes he’ll say, ‘Can I just eat pasta and leave me alone?’ I want to make a spinach salad and meatballs, and he just wants an Oreo for dessert.

Imagine what my sons must think this is all about—imagine, five or 10 years from now, asking Emile, what did you think?

I asked him, “Can’t you finish up the meatballs?” and he said they were a little too spicy, because he thinks pepper is spicy. All he wants is the Oreo, you know? And he gets this facial expression as though the rest of it is the most disgusting thing he’s ever eaten.

Cooking, now, is definitely my source of relaxation, cooking for me, for us, at home. It’s a nice hour, hour and a half, an escape from reality. I can make what I want, know that I’m making something the kids will eat, or try something new, or have them get involved. They’re doing distant learning, and the project yesterday was to bake or make something that involves fractions. So we made Swedish waffles. I think it’s fun for them to see how these worlds collide. Imagine what they must think this is all about—imagine, five or 10 years from now, asking Emile, what did you think?

It’s a silver lining, to be with my family. One of my goals, starting out, was to be able to choose on my own, by the time I was 40: do I want to go to my son’s soccer game if it’s 6 p.m. and the restaurant is bustling? It’s very personal. When I used to think about growth, the very first question I asked myself was, is it compelling and worth doing, because it’ll take time away from my family. Maybe at first, as we open a new place, I don’t get to go to that game my son’s really excited about playing in.

Cooking at home has become a source of relaxation for Kaysen to escape from reality. Sometimes his kids Julius (foreground) and Emile (background) join him in the kitchen.

Dave Puente

I had gotten to the point, before all this, that if Emile had a soccer game at 6:30, I could leave, go to his game, be back at the restaurant by eight, and it wouldn’t be the end of the world at the restaurant—but if I didn’t go it could be the end of the world for Emile, who’s so excited. That’s my filter.

The home gym

The last couple years I’ve had a pretty strict workout regimen. I have—I had—a trainer Monday, Wednesday, and Friday, he gave me homework on off-days and I’m strict about my time there. It’s six hours a week, the six hours I turn my phone off, you literally cannot get a hold of me, always blocked in my calendar. The most important call you can imagine that hits at that time, we ask to reschedule.

All that’s thrown off, the gyms are closed, so I text my trainer to find out what I’m going to do today. He sends me a list of five things I can do in 30 minutes, in my basement. And the boys had this really cool program at school, I’d drive them over, drop them off, and from 7:55 to 8:35 they have fitness club in the gym with their teacher, jumping jacks, stuff like that, effectively to get their minds awake—instead of getting out of bed, grabbing breakfast, and going right to school.

Now they come downstairs with me, maybe 10 minutes, and then they go and leave me alone.

—

Dave Puente/Nicolas Raymond/Flickr/Graphic by Talia Moore

The retooled restaurant

From my vantage point, we almost have to restructure all the businesses, take advantage of everything we’ve learned and say, If we were going to do all this again, with five-and-a-half years’ experience at Spoon and Stable, three at Bellecour, one at Demi, if we look at all that experience and all the data, how do we thrive? Not just survive.

Takeout gives us a structure to the week, which has been a blessing, but at some point we will have a discussion: If this lasts until July do we want to do this, or stop, or do something different? There is endless possibility here.

The rules have changed, the rules of engagement—and I don’t yet know what it’s going to look like when we come back. There could be a complete or large wipeout of neighborhood-focused restaurants, and we have to fight for them in a different way. And Amanda Cohen wrote a great piece in The New York Times about owner-operated and fine dining restaurants, where she asked, if you used to pay $5 for that latte and now you pay $8, but you recognize that $3 helps the person serving it, gets them health insurance or better wages, would you pay it? That’s a valuable question.

There are hundreds of people who rely on our business to pay their mortgages, pay their bills, live their lives.

Charities used to come to us and ask us to give away a table for six, and they’d promote us in their brochure, but what are we giving away? Revenue. Maybe that will change, and they’ll give us $100 per seat to cover our labor because they want to take care of our team, which adds value to the restaurant and helps our ecosystem. And we’ve always discounted things, which is not good for us or for the farmers. You sell a steak for $25 because the one down the street is $24 and you don’t want to lose customers. But if I’m not making any money on the steak, why am I putting it on the menu?

The model when we re-open has to be different, and I’m 100 percent focused. There are hundreds of people who rely on our business to pay their mortgages, pay their bills, live their lives. It’s scary now, but also motivating. How are we going to fight for this?

Andrew Zimmern said to me, The house is burnt. Now you get to rebuild it. We have to figure out how.